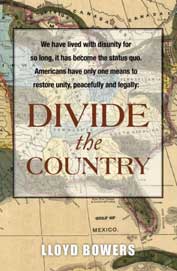

Divide the Country!

My book takes stock of America's predicament--its division into warring sides, and its frustration and paranoia increasing in a political stalemate--and comes up with a fairly outrageous solution: divide the country. Elected officials may agree with such a plan, but promoting it publicly could be an election-killer. Fortunately, the split in the electorate is a fait-accompli--as evidenced by the rancor following the Trump presidency--and it succeeds where political-will fails. Americans only need to respond pro-actively to the split and restore unity to the successor nations. We cannot save a nation dominated by hostile rhetoric. We cannot employ the dictatorial measures many see as the only way to resolve the disunity--the by-product of America's success. America is the last great hope for so many people, they want to turn it to their advantage; but America does not succeed because of voting patterns; it succeeds with foundational documents that facilitate effective governing.

Buy Now

DIVIDE THE COUNTRY,

Oprah Winfrey and 60 Minutes

After the election of Donald Trump in 2016, television hostess Oprah Winfrey assembled a panel of ordinary Americans for CBS Television's 60 Minutes program, and asked them to assess America's post-election political climate. Winfrey and 60 Minutes made sure the panel consisted of an equal number of Clinton and Trump supporters. The sixteen-minute segment, aptly titled "Divided" by 60 Minutes, ran on September 24, 2017, and featured a combustible exchange of opinions that needed little prompting from Winfrey. It took a lot of Americans by surprise.

An article published the next day in businessinsider.com reported, "Winfrey revealed at the end of the segment that the heated conversation had lasted for three hours, and continued in a restaurant after filming ended." The report also said the panelists themselves worried about the division in their group: "A woman named Laura said she felt the country will become more divided, and that she feared 'civil war'. Most of the group agreed with this sentiment."¹

Variety's on-line news service quoted one panelist who complained, "We do not understand each other. And when we're talking, we're talking different languages." Variety opened a comments-page for the 60 Minutes broadcast. The fifty-three reviews reveal a soreness in the public consciousness over the political division in the nation, suspicion about the intentions of the opposing parties, and even resentment toward Oprah Winfrey for hosting the panel and opening old wounds.

One commenter said Winfrey was to blame for "lighting the fuse and watched (sic) as both sides . . . chewed each other apart." Another admitted that "for the first time, I feel scared and like (sic) the country has been taking (sic) over by someone [President Trump] who cares only about himself." A third commenter said, "The country was already divided before trump (sic)," while a fourth stated, "Obama was the real divider of our country."²

Readers should note that the 60 Minutes panel-discussion and viewer-reactions around the country reveal a lot of anxiety in so-called average Americans over the future of the nation, although neither politicians in Washington nor college professors at Harvard and Stanford, can hear them very well from their ivory towers—not that average Americans really have much to say to their politicians. Most of them have, at best, a vague sense of how politics work.

Former CBS anchorman Dan Rather offers Americans a reassuring viewpoint of the conflict in his new book What Unites Us. I would respect him more if he wrote about what divides us to reflect his stormy career at CBS. Rather's positive sentiments are too little, too late. He may genuinely want unity for the nation, but under Democratic leadership, which half the nation emphatically does not want.

Most leading journalists have written something about the disunity. Conservative journalist David Brooks published his view in the New York Times's New Year's Day issue, 2018, titled "The Retreat to Tribalism." Brooks laments that political rhetoric "emphasizes having a common enemy." Public figures in the opposing party are represented as "oppressors acting to preserve their privilege over the virtuous oppressed."

Brooks's article does not emphasize enough that America's disunity stems from disagreement over important issues: the needs of the country, the policy initiatives it must undertake, and the role of the government. If the disunity did involve just political rivalry and the sour grapes that result from losing, we could live with that. The U.S. holds a presidential election every four years. One party wins, the other loses. We hear them butting heads over current events everyday.

Each side belabors the other's political partisanship and abuse of the spoils system, fueling an us-against-them mentality. With so much wealth at stake—so many valuable American assets—envy and resentment grow into a potent force in their own right; but, again, real differences in politcal and philosophical orientation have caused the division, not simply partisan politicians, cable-news talking heads, or other journalists.

Either way, the political parties spend all their time obstructing each other and cannot maintain a sense of direction at the helm. Neither party can lead except by hoodwinking or intimidating the opposition. The 60 Minutes panelists speak their minds bluntly and suggest an end-game at work, people looking for a way out, frustrated over the lack of coherent leadership and the few options remaining for them. The viewer does not have to read between the lines to pick up their fear and mistrust. Once we admit it has gone this far, how do we react?

First, Americans need to appreciate how the relentless strife affects them—not simply recognizing the intellectual facts, but also the cost to their happiness and confidence in the future. When Variety reports that "tensions are so fraught," it means more than simply combative leglisative sessions or feuding political figures. It means that intimidation and fear may lead to armed conflict.

It really means pain and paranoia hamper the forward progress of the nation and poison it socially.

Even Americans sequestered in gated communities and leafy colleges must notice the stress. They may shrug it off. They should not ignore it. Most Americans want to have children and, after that, grandchildren—hostages to fortune. And the worst part is, average Americans have to do the lifting to resolve this situation, not the politicians. What an inconvenience if we already pay the politicians to manage our government for us.

I do not blame our legislators, our public executives, or politics as a career, but the disunity requires someone outside the box to take action. Presidents and members of Congress do not get elected by acting nonpartisan and forward-looking. They do not say nice things about the opposing party, but do just the opposite—act partisan and belligerent for no reason at all. The true-believers who serve them will accept nothing less than combative commitment. They do not get paid to ask where all this partisanship is taking us. The journalist Ronald Brownstein quotes former President Lyndon Johnson in an interesting book, The Second Civil War: "It is a politician's task to pass legislation . . . not to sit around saying principled things."

Real issues divide us; but then the psychology of disunity takes on a life of its own, like football fans who start lining up at a ticket booth at 4:00 a.m. before a football game. What we have now resembles people lining up to attend a battle, like the spectators who brought picnic lunches to the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Most had no idea that the roar of gunfire and artillery would be so loud. As they fled the scene, they must have had second thoughts about a civil war.

Let the memory of the Civil War remind us not to ignore the disunity and resentment in our nation. One consequence is that America could get better candidates for our nation's highest office, but the true-believers want someone hard-hitting. In a 1998 interview, Matt Lauer interviewed future 2016 Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton: "You have said, as I understand it, to some close friends, that this is the last great battle, and that one side or the other is going down here."

Mrs. Clinton answered, "Well, I don't know if I've been that dramatic. . . . The great story here, for anyone willing to find it and write about it and explain it, is this vast right-wing conspiracy that has been conspiring against my husband." Mrs. Clinton's handlers insisted that she did not originate this phrase. A Democratic operative Chris Lehane says he did. She just borrowed the phrase—the way people borrow pencils, automobiles, or firearms.

Donald Trump believes in a vast left-wing conspiracy. Republicans often use the term "Deep State" or "Administrative State." President Trump did not win the Republican nomination because of his competence as a debater or his knowledge of current affairs. His debate with Mrs. Clinton showed him with poor debating skills and a limited knowledge of domestic and foreign affairs. Trump won because he came out swinging with a "someone-is-going-down-here" stance, which he continues to employ.

On March 22, 2018, President Trump took a swipe at former Vice-President Joe Biden with a tweet to his on-line admirers: "Crazy Joe Biden is trying to act like a tough guy. Actually, he is weak both mentally and physically. . . . Don't threaten people, Joe." Die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung ran a lengthy news analysis of Trump before the election titled "Be a Killer. Be a King." It gives a reader a problematic view of him, but this posture won him the election.

Each election, the political parties promise payback and a disabling of the opposing party's power structure. Thankfully most politicians have more bark than bite. True-believers feel betrayed when they see their politicians compromise on the issues. The politicians may chafe at the criticism they receive, but they have to share congressional space with their opponents and have no choice but to cobble a deal in the legislative process to get anything done. If the parties dig in their heels and stop negotiating, the government shuts down.

Since the election of 2016, accusations of dirty dealing and intimidation have gone back and forth. Not only does the public internalize the paranoia, but the loss of trust means more people want to neutralize the opposition before they do anything to help the nation. The disunity and resentment has created two embattled nations coexisting uneasily under one roof. We need to think about how this hurts our national morale and preparedness.

To recap, an irrevocable split has already happened. With so much hurting and hating between us, it is too late to change the rhetorical tune for any practical benefit. To repair the damage, we have to divide the country. Conveniently, in our case, the division has already happened—in attitude if not in formal declaration. It is short-sighted to say, "Wait till the next election! We'll fix those blankety-blanks!" We are all "blankety-blanks" in someone's eyes, if you stop and think about it.

I do not claim to have a cure for sin, and I accept that mankind consists of a mixed bag of personal traits. The best a society can do is to set up regulatory systems that enable people to function at their best. For that reason, I want to let the warring parties depart into their domains, their stances and prejudices intact.

We can only go forward by unhitching the embattled citizenry from their common yoke. No more surface, rhetorical remedies. Basta! Once America divides, the new countries' paths will diverge from the get-go. Each side will recover trust and unity among fellow believers—trust in a common vision for the future.

photo: Doug Deas

George Washington, 1732-1799; General and Chief of Staff of the Continental Army, 1775-1783;

First President of the United States, 1789-97;

. . . And if the assembled delegates decided not just to revise the Articles [of Confederation] but to replace them altogether with a new government, Washington's presence would provide an invaluable veneer of legitimacy, [since that was] strictly speaking, a violation of the mandate.

(The Quartet, page 107)

"No man in the United States is, or can be, more deeply impressed with the necessity of reform in our present Confederation than myself."

(Ibid. page 108)

As he saw it, the Confederation Congress had sustained that ignoble tradition . . . in its deliberate embrace of indifference and inadequacy. [Washington] believed that, "We are either a United people or we are not."

(Ibid. page 109)

"The Unity of Government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main Pillar in the Edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad, of your safety, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize."

(Washington's Farewell Address, page 5)

Strive for Unity

As President George Washington served out the last years of his second term, he made it known he did not wish to serve a third term. On September 19, 1796, he gave his last official address before the U.S. Congress, the Farewell Address. As the father of the country, nearly everything he did set a precedent for the men who succeeded him. Every president since Washington has given a farewell address, although few have the gravitas and distinction of Washington's original.

He had worked on the Farewell Address since the last year of his first term, before he knew he had to serve a second; and he knew what he wanted to emphasize: the preservation of the nation's unity. America needed unity in order to survive and prosper. Disunity had already begun to rear its ugly head, and he knew it could endanger the young republic. He had watched his former allies Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine turn against him.

His enemies commenced a smear campaign against him. The historian David McCullough writes in his biography of John Adams that Washington became "weary of the demands of the office . . . and disheartened by party rancor and a severely partisan press that had taken to calling him an American Caesar." As his second term began, he said, "May Heaven assist me, for at present I see nothing but clouds and darkness before me." His response to the hostile press and his fear for the future reveal a vulnerability that the public never saw.²º

In the text of his Farewell Address, he uses different forms of the word "unity" fourteen times in the first thirteen pages. On page two, he refers to the "uniform sacrifice of inclination" and "unanimous advice of persons." He also uses the phrase "constancy of your support" on page four and "common cause" and "common government" on page seven.

Starting on page fourteen, Washington warns Americans about disunity, enabled by a "faction" or a "party." He explains that "the will of the party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority," seduces voters with "ill concerted and incongruous projects of faction" until they become "potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men . . . usurp for themselves the reins of government."²¹

When I read these words the first time, I remember feeling wonderment about the man's foresight. On an episode of "America's Funniest Home Videos." A man asked a little boy why he was crying. He said, "I miss George Washington." Anyone who saw the program had to be touched. We all miss Washington. He wanted unity and warned us about dividing into factions.

He fought hard to achieve unity; and look how disunity has taken over. He would not be pleased; but Ellis writes that Washington was also a "rock-ribbed realist." He had toppled two governments during his lifetime. He surely would have no qualms about dispatching a third, if he felt his actions would restore unity without bloodshed.²²

If he were alive today, I do not think Washington would change his mind about unity. We need it as a practical matter—even modern America with all its complexity. He would accept that our nation has to achieve proper government through the electoral process and harmonious policy-making in our legislative bodies. If we do not have those things—and it is clear that we do not—then we have to reassemble the American jigsaw puzzle in a way that gives them to us again.