Freedom is a Public Utility

The most available energy source in our nation is the individual initiative of its citizens; so we should establish an environment that enables lasting initiative. Offer the nation's foundational docun1ents as legitimation for it, to explain its reason for being. Convey the ethos of initiative in the nation's culture: its literature, music, media, and educational systems.

In the end, one must also admit, freedom is a double-edged sword dynamism and wealth but also risk, chaos, and inequality. Dictatorial societies never have the law-enforcement problems or inequality that free societies have; so trying to convince everyone to go along with the utility of freedom will be an uphill battle.

Buy NowThe Siegling Letters

My mother was at my grandmother’s house in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1993, toiling through Granny’s personal effects.

At the end of a dark, narrow clothes closet, she saw a nondescript shoe box. She peeked inside and saw a stack of nondescript letters written on paper aged to a drab gray or splotched brown.

They were not inside envelopes; they just folded over like aerogrammes and sealed shut with a smudge of red sealing wax. I could see they predated postage stamps or even a nation-wide postal service. On the front side was the name of the addressee, “John Siegling,” in Charleston, South Carolina, written in large, cursive script, and some postmarks.

They were not inside envelopes; they just folded over like aerogrammes and sealed shut with a smudge of red sealing wax. I could see they predated postage stamps or even a nation-wide postal service. On the front side was the name of the addressee, “John Siegling,” in Charleston, South Carolina, written in large, cursive script, and some postmarks.

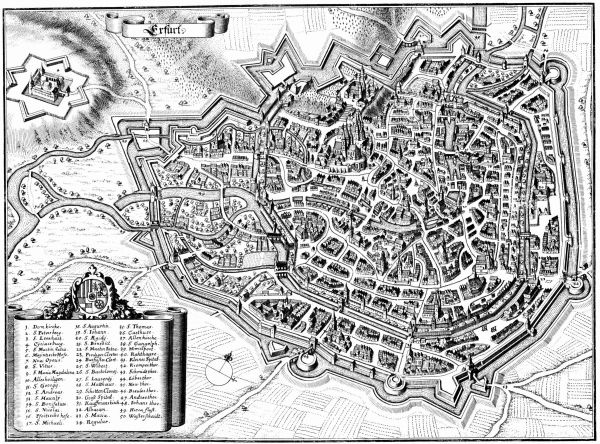

John Siegling is my mother’s paternal great-grandfather who came to this country from Erfurt, Germany, in 1820. The letters had been written by members of his family still in Germany. Their names appear on the back side, with additional postmarks that letters typically accumulated as they passed from one country to the next, but with no return address. A letter needed two months to arrive. No one would have bothered to return mail en route for that long.

In all, the collection is about fifty letters—seventeen written by my Great-Great-Great-Grandfather Johann Blasius Siegling of Erfurt.

Triple-G’s letters are by and large simple accounts of a pious, hardworking man and woman and their determined, hands-on approach to paying bills and raising sixteen children, of whom only eight lived to adulthood. The deaths of two children are reported in the letters. Triple-G’s scribbled handwriting bears witness to his grief or prostration.

The collection of letters also includes nine from Ottilie, written between 1838 and 1857. These letters include postscripts from other family members. Triple-G has a schoolmaster’s competent penmanship. Ottilie, on the other hand, spells some words phonetically, reflecting her Erfurter dialect. Thus, “to lead,” führen, she writes as fieren. She mentions Erfurt’s Botanical Garden and writes it as der Potanischer Garten. She reverses “B” and “P” as a matter of course. Thus, the word “patrols” appears as die Batrollien. The “Public” is das Bublikum. Ottilie also writes die Kirche, the German word for “church,” as Kürche. Auntie Ottilie never married and was always assisting her siblings and their children. Her family news is over-involved; her take on current events pedestrian and conservative.

And finally, John Siegling. Jr. contributes his own letters. His mother and father had sent him to live with the Sauls in Alach, an agricultural village near Erfurt.

In his letter to John, Pastor Saul reports that John, Jr. has made much progress in his schoolwork. John, Jr. agrees in his own letter that he studies diligently. The style of their respective handwritings hint at the kind of people they were: Pastor Saul writes in a thick, dictatorial, head-long scrawl that is difficult to read—quite a contrast to John, Jr., whose penmanship is primly immaculate but lacks character. The poor boy addresses his parents with a painful formality and restraint, as if to get back into their good graces. Not surprisingly, he is homesick for Charleston.

The Thousand-Year-Old City

“A foreigner who wants to become a citizen of Erfurt must pay twenty Groschen and bring a leather bucket for service in a firefighter brigade.” (Book of City Ordinances, Erfurt-Bindersleben, 1745.)

As I read the letters, I found myself attracted to Erfurt, itself, as an example of collective human drama and societal evolution, eleven hundred years of it. Like so many really old places, Erfurt bloomed early, from about 1100 until 1650. Since then, it has had its share of ups and downs—more of the down side really, especially in the last century, starting with the decline in the competence of the monarchy, then experiencing with the rest of Germany the loss of World War I, the catastrophic inflation of the 1920s, and the ascent of the Third Reich, and finally East Germany’s wretched status as a Soviet Satellite during the latter half of the twentieth century.

For visitors, the real surprise is how intact Erfurt is. Another surprise is the cosmopolitan character of Erfurt’s Renaissance-era buildings, called Patrizierhäuser, a clear sign of Erfurt’s former wealth.

Etchings from the seventeenth century show the fortifications in their splendor

photo credit: Erfurt, 1650, Merian, courtesy of Erfurtweb.de

If you consider the frequent wars raging at the time, it is probable the buildings would never have survived, except for the fortifications.

Even the generic name for the residents of a walled city, Bürger in German and Bourgeoisie in French, show how much the walled city, die Burg, defined wealth-creation in Europe at that time. Nearly every trace of the fortifications is gone now—demolished in the late nineteenth century in order to increase access to the fast-growing city. Thanks to the peace in the unified Germany (1871), the city no longer needed them.

After World War II, the Soviet Red Army occupied the eastern provinces of Germany and used them to create a new nation, the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany. The new Soviet-style government confiscated the Patrizierhäuser, along with most business enterprises, and designated them as Volkseigener Betriebe, meaning that private property had become “the property of the people.”

Then came die Wende in 1989 and the Reunification.

The new Germany abolished the Soviet Socialist government and asked redevelopment engineers from the West to do an appraisal. Writers and photographers also crossed into the former East Germany for their first look at the former Workers’ Paradise. For most, it was their first uncensored view, and they could hardly believe their eyes.

Obsolescent factories had spewed untreated waste into rivers; Residential furnaces burning high-sulphur coal had literally poisoned the air during long winter nights.

Coal still powered the ancient, smoky locomotives on branch lines, long after the rest of Europe had gone over to modern diesel trains. With no capital to expand the economy, the coal was all East Germany could afford. Telephone exchanges ran on equipment manufactured in the 1930s.

Individuals who refused to identify themselves spoke to Western journalists and took the government to task for not making timely repairs to properties they owned. The problem was, once again, lack of available capital. For a totalitarian regime vehemently opposed to capitalism, why should that surprise anyone?

Some of my Siegling relatives travelled to Erfurt soon after the wall came down for a first-hand look and to meet their Erfurt relatives. During an uneven conversation helped by an interpreter, the Erfurter Sieglings glanced around them for snoops and informers. With a mix of fear and perhaps shame, they admitted, “We had our children baptized.”

Their confession surprised the Americans. . . .

Their confession surprised the Americans. . . .

I saw Erfurt for the first time in the summer of 1998. Rebuilding had gone on for nearly nine years, and still much remained to be done. There were five construction cranes just in the vicinity of the Domplatz, stacks of building material parked everywhere, and scaffolds covering buildings. . . .

With so many investigations to find out what had really happened in East Germany during the Cold War, there were bound to be surprises. Dr. Thomas Nitz recounts one in his book, Stadt—Bau—Geschichte, or “City, Architecture, and History.” Nitz writes that Kurt Göldner, a scholar at Erfurt’s City Archive in the 1950s and 60s, had read through historical documents held by the Archive and discovered that the medieval ruler of Erfurt, the Archbishop of Mainz, had made individual freedom and ownership of private property a hallmark of his administration, as the means to create wealth.

photo: Volkmar Birkholz

Göldner undoubtedly took risks with his research, since it tended to validate the two institutions hated most by Marxists. He put his research in a safe place before his death in 1965, in the hope a future researcher might happen upon it and recommend the nearly thousand-year-old concepts again. I asked scholars at the city archive how Göldner could have escaped notice by East Germany’s hated secret police. They assured me the East German leadership regarded the archbishop’s model of a market economy as a harmless antique.

“The most important aspect of re-establishing Erfurt,” Dr. Nitz states, “was instituting personal freedom through the ownership of real estate,” called Freizinsrecht in German. Citizens of Erfurt could own a parcel of land with the payment of a yearly tax, or Zins. If they kept up their payments, they could do whatever they wanted with it. The original Latin-language document describes the principle behind the Freizinsrecht as libertas et iusticia—liberty and justice—“regardless of a person’s origin or personal circumstances.”

It reminds me of a clause in the American Pledge of Allegiance, to ensure “liberty and justice for all.” The legal foundation created a Rechtsgemeinschaft, writes Dr. Nitz, so Erfurt became “a community of citizens protected by a body of laws.” (page 58 & 65)

THE RESENTERS

Freedom is like the sun, one of the quiet essentials. As a public utility, it is hardly more grand than switching on a light or running a load of laundry. It requires planning and maintenance. Much of the time it runs untended, like wind farms or solar panels.

One morning, the lights went out in my home in Charleston, South Carolina, and I nearly had a fit. We need warnings, once in a while, to remind us of the stakes. . . .

Benjamin Franklin’s approach to freedom was a terse admonition inscribed on the coins and banknotes he printed for the young United States: “Mind Your Business.”

Donovan Leitch delivers his own take on freedom in a song from the late 1960s called “Riki Tiki Tavi,” derived from The Jungle Book, by Rudyard Kipling.

Donovan suggests we learn to kill our own snakes:

Everybody who read The Jungle Book knows that Riki Tiki Tavi’s a mongoose who kills snakes.

When I was a young man, I was led to believe there were organizations to kill all my snakes for me;

.e., the church, i.e., the government, i.e. the school;

But when I got a little older, I learned how to kill them myself.

That is the ideal in a free society, in a nutshell: Mind your business and kill your own snakes; but Donovan recognizes in the next stanza that society is often not on a good footing:

People walking around, they don’t what they’re doing.

They been lost so long, they don’t know what they’re looking for.

Well I know what I’m looking for but I just can’t find it.

I guess I gotta look inside myself some more.

Something gums up the spirit of inquiry in people. They can stay lost in a society with dumbed-down media values and hardly know it. A lot of them end up on the sideline watching the tumult of society pass them by—held back by internal blocks—and turn resentful. . . .

Kill On Command

John Frankenheimer filmed The Manchurian Candidate in 1962 with Frank Sinatra and Angela Lansbury. For Americans who grew up in the Cold War years, the film remains a milestone, both for its treatment of Soviet expansionism and tacky American false-patriots. . . .

The opening scene of an American platoon during night patrol is titled “Korea, 1952.” Soviet soldiers rise up from the dark and ambush the Americans. Green helicopters with a red star on their tail fins take the Americans away. . . .

The Americans are taken across the border to Manchuria, where a Sino-Soviet task force led by a cosmopolitan Chinese psychiatrist starts work on them with an “implantation team.” The psychiatrist later tells task-force members he has heard of “brainwashing” from news reports, but boasts the Americans’ brains “had not merely been washed, they had been dry-cleaned.”

The purpose of it, he tells his audience, is to advance revolution in the United States. He will use a programmed assassin to kill on command and not remember it. To this end, he has selected Sergeant Raymond Shaw, a member of the patrol and an average-looking man, to carry out his plan. . . .

The psychiatrist paused to get his audience’s attention and declares, “It is difficult to define true resentment,” but he knows Shaw has it and values him for that reason: “[T]he resenters, those men with cancer of the psyche, make the great assassins.” (page 43)

Hatred in a person focuses on a particular hated target, which the psychiatrist does not want. He wants a resenter who feels the same contempt or disregard for all. A resenter cares little for understanding and is indifferent to others’ feelings. Moreover, he is socially and sexually timid, “and this weakness of will is compounded by his need to lean upon someone else’s will.” (page 43-4)

The psychiatrist proves this when he asks Raymond:

“Whom do you dislike the least in your group who are here, today?

“The least?”

“That’s right.”

“Well—I guess Captain Marco, sir.” [Raymond’s commanding officer]

The psychiatrist nods his approval and says to the assembly, “Notice how he is drawn always to authority . . . .”

“Pity Raymond, if you can,” the psychiatrist says enigmatically. . .

The 2003 edition of The Manchurian Candidate (contains) a curious introduction by an American academic Louis Menand. He makes observations that are, in the balance, more disapproving of the novel than approving. He writes that . . . Condon’s knowledge of psychology is slapdash. Besides, the novel’s story about brainwashing soldiers to become assassins is mostly a product of anti-Communist hysteria. In other words, read something else. (page vii-xiii)

I suspect that, however good or bad it really is, The Manchurian Candidate and its hair-raising story of an American Everyman’s secret timidity, resentment, and need to lean on someone else’s will, touches nerves among the intelligentsia. . . .

“Let us say a weakening of the personality to the compulsive process,” says a Dr. Reichman in Ramona Stewart’s similarly slapdash novel from 1971, The Possession of Joel Delaney.

Hitler is my Weapon

Dr. Josef Goebbels, PhD: writer, propagandist, and kingmaker, was responsible perhaps more than anyone else for promoting Adolf Hitler in the burned-over, receptive soil of post-World War I Germany. His gifts were extraordinary: he was musical, literary, he loved art, and he had wrestled a Ph.D. out of the stingy university in Heidelberg. . . . In his diary, however, which he calls his Beichtvater, or priest-confessor, he makes a grave admission, describing himself as "eine Demagoge, schlimmster Sorte," or demagogue of the worst kind.

Goebbels admits to telling more lies to the German people than seems possible, and proclaiming myths about the Third Reich that were preposterous on their face. “I didn’t believe them myself,” he writes, “but I wanted to.”

The German news magazine Der Spiegel went public in 1987 with a story about the Goebbels diary, titled "Meine Waffe Heißt Adolf Hitler," or “My Weapon is Named Adolf Hitler.” The title is interesting—not Hitler wielding Goebbels, but Goebbels wielding Hitler, and to what end?

“Revenge!” Goebbels snarls in his diary. “Who cares for what reason!” But essentially because he is a spindly man with “an oversized head and a club foot.” In his diary, he makes no secret of his desire for power; so he does what resentful people do, leans on someone else’s will: “The more power I imagine my lord to have,” Goebbels writes, “the more majestic and powerful I become!” It is a source of competition between the power-seeking followers of Hitler. Thus, Goebbels admits to hating most of the other leading Nazis.

Goebbels admiration of Hitler led to a certain radicalization: “His mission burned in him like a pyre.” Goebbels describes himself laughing with glee over “the destruction of everything holy and civil.”

Goebbels’s mission was not just to wield Hitler as a weapon, but to exploit the average German as well—the “weak, lazy, and cowardly Volk.” Whatever the Germans really thought of the “ruling Nazi bandits,” Goebbels writes, they were not to know he felt only contempt for them . . .

“A special weapon for dumbing down the German people,” Der Spiegel quotes Goebbels, “is broadcasting.” Broadcasting is, “the spiritual weapon of the totalitarian state . . . . Every German home shall have a radio.” With broadcasting under the control of the Nazis, they could “disseminate Nazi indoctrination continuously,” and make it an “emotional roller-coaster. One moment, shrill pathos and touching remembrances; the next moment, open threats, followed by heavenly promises . . . brainwashing [Gehirnwäsche] by the millions.”

William Sheridan Allen writes in his remarkable book The Nazi Seizure of Power that other Nazis thirsted for pay-back. Allen studied the emergence of the Nazi Party in a German town by combing through its official records and by interviewing eyewitnesses. To conceal the town’s identity, Allen named it, “Thalburg.” The town’s nervous residents asked Allen to conceal their names, as well; so he did. The local Nazi leader in Thalburg is “Kurt Aergeyz.” The pseudonym Aergeyz is pronounced the same as Ehrgeiz, the German word for “ambition.”

The news magazine Der Spiegel bought a copy of Allen’s book and did some sleuthing on its own. It discovered the next year that “Thalburg” was in reality Northeim in Lower Saxony. The magazine also unmasked many of the townsfolk whom Allen had interviewed. “Kurt Aergeyz,” for instance, was in reality Ernst Girmann. Allen must have winced at the liberties Der Spiegel took, but the magazine’s editors were clearly intrigued with his research.

Girmann was no ideologue, Professor Allen writes in his follow-up edition. When the respectable, “ideological” Nazi Wilhelm Spannaus wanted Girmann investigated for misusing Party membership dues, the Nazi higher-ups told Spannaus to keep quiet about it. They knew Girmann “was just the man they wanted.” (page 246)

Since ideological loyalty did not weigh heavily in Girmann’s actions, Professor Allen wondered what drove him to succeed as a Nazi:

Nothing is more difficult to discover than the truth about personal motivation, but many of the actions taken by Girmann and his closest friends suggest they were the product of social resentment. Girmann was of the lower- middle class, and this undoubtedly made its mark upon him in a town where government and society were dominated by an elite that freely expressed its cool sense of superiority. (page 300)

The Nazis must have had a proofing plan similar to that used by the psychiatrist in The Manchurian Candidate, since they understood which type of person produced the results they wanted.

The level of resentment in a society is the best measurement for the risk for dictatorship. How resentful are its players? Resentment exists mutely in the shadow of freedom, biding its time with gnawed fingernails and vindictive thoughts, and waiting for someone to organize it.