"CHARLY" the movie

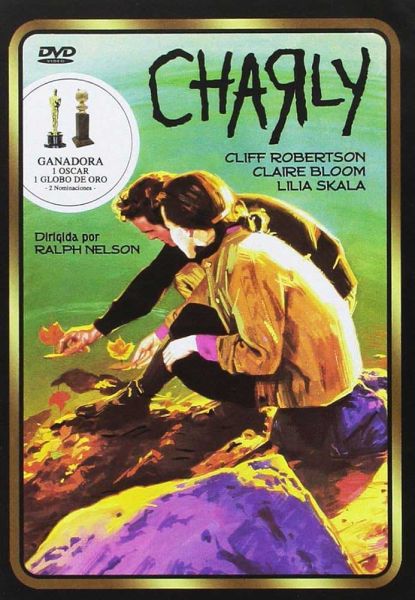

The movie CHARLY came out in 1968, starring Cliff Robertson and Claire Bloom. Ravi Shankar, the Indian sitar-player, provided the soundtrack. It had a high-end, 1960s orientation that allowed it only a short run in theaters, then it disappeared from view. I did not actually see it until the late '70s when the public library in my hometown showed CHARLY during a weekly film program that it hosted. My readers can watch it for free, now, on YouTube.

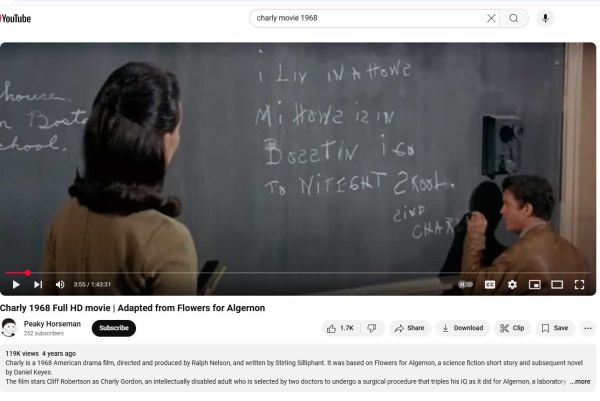

They may not connect to CHARLY like I did. It is the kind of movie I can never forget. In the snip from the movie, the viewer can see middle-aged Charly Gordon in night-school struggle to write a simple sentence on the blackboard. He is left-handed like me, and although his spelling is terrible, Charly never stops trying. He has to try. Learning does not come easily for him.

Not long after I saw the movie, I found a copy of the novel Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes that forms the basis for the movie. Keyes published it in 1966, hardly two years before the movie came out. The producers must have seen it coming and snatched it up. But by the time I bought my copy, it lay moldering in a little second-hand bookstore, aptly named "The Bookworm".

If the tone of my writing impresses my readers as melancholic, I can tell them there is a reason for that. The movie CHARLY concerns a retarded man who undergoes brain surgery to improve brain function. Before the surgery, he worked in a bakery as a janitor. In spite of his disability, he works diligently and sincerely. In his core-self, he glows with a gentle good-nature, accepts being the butt of his co-workers jokes with good humor, and shrugs off their occasional cruelty to him.

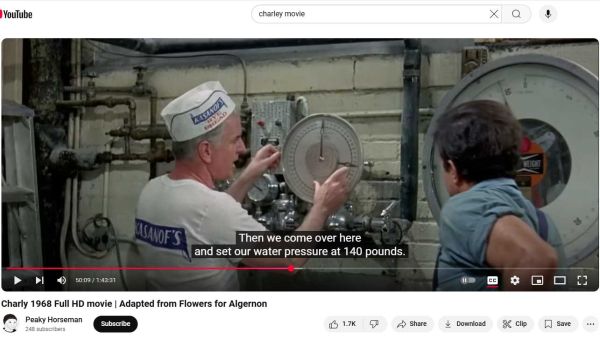

After the surgery, everything changes for Charly. His co-worker Gimpy challenges him to run the bread-making machine. Gimpy explains to the others that if Charly screws it up, they can take the rest of the day off and go home. But Charly doesn't screw it up. Gimpy gives him the instructions, and he runs the machine flawlessly.

The other workers tease Gimpy over his needing two weeks to learn how to run the bread-machine, and it sours Gimpy's relations with Charly right away. Charly is no longer Gimpy's mental inferior, but much more intelligent, now. As Charly becomes more capable, the other workers can no longer tolerate him. Daniel Keyes never mentions a labor union. He only says that the other workers told the bakery-owner they did not want Charly there any longer and demanded that he turn Charly out. His increased intelligence turned the other workers against him. His high intelligence cost him his routine and his main peer-group. The losses deeply affected Charlie.

Like Charly, I did terribly in school, thanks to dyslexia. Year after year, in spite of my hard work, I suffered humiliation for having poor grades. I hated having to show report cards to parents, but they only said to keep trying. Then, I graduated and started work and realized gradually that I had some brains, after all. So, I feel a lot of kinship with Charly Gordon.

And like Charly, I had a decision to make: remain at the metaphorical bakery with my homies, wait for them to turn me out, or strike out on my own. I'm guessing or extrapolating that most of us have to make similar decisions, that it's just part of growing up—leave behind the wide, confiding smiles and happy hi-jinks of youth. It helps if you continue to try to learn, like Charly.