A Dissident's Dictionary: Fahrenheit 451 2

Note Barack Obama's complimentary quote.

Guy Montag meets a teenager named Clarisse McClellan at the beginning of the book. She goads Guy to review his life and start on a new course:

Page 9: He was not happy. He recognized this as the true state of affairs. He wore his happiness

like a mask, but (Clarisse) had run off across the lawn with the mask, and there was no way of

asking for it back.

Page 60: What was it Clasrisse had said one afternoon? "My uncle says there used to be front

porches. And people sat there sometimes at night, talking when they wanted to talk, rocking, and

not talking when they didn't want to talk. Sometimes, they just sat there and thought about things,

turned things over. My uncle says the architects got rid of the front porches because they didn't

look well. . . . they didn't want people sitting like that, doing nothing, rocking and talking; it was

the wrong kind of social life."

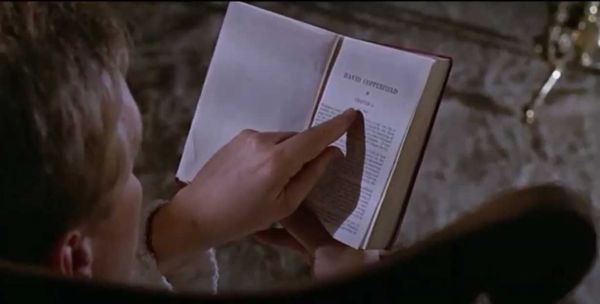

Books exert a strange magnetism on Fahrenheit's main character Guy Montag, who frets over his empty life and meaningless marriage to the other main character, Mildred. Guy is so indoctrinated, he cannot detect his loss of personal values, cultural orientation, and sense of direction. Maybe the books will give him some clarity or perspective. Note that he is reading from David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens.

Bradbury published Fahrenheit in 1953. Just think: in 2023 Americans will celebrate its seventieth anniversary. My reader can pick up a copy of Fahrenheit for a song. Its Amazon page has received over 20,000 mostly positive comments! Schools should make it required reading, but they probably won't. It just rankles too many people, even now.

Many Americans may start Fahrenheit 451, but it will upset them so much, they will stop dead in their tracks—when they realize how well Bradbury predicts the future. He calls the first techno-toy a "Seashell," like ear-buds:

Page 10: "In her ear, the little Seashell, the thimble radio tamped tight, and the electronic ocean

of sound, of music and talk and music and talk, coming in on the shore of her unsleeping mind."

The "parlor walls," basically large, flat-screen TVs that broadcast inter-active programs:

Note how the TV commentator pays dues to "Tolerance and Diversity."

Page 42: What was it all about? Mildred couldn't say. Who was mad at whom? Mildred didn't

quite know. What were they going to do? Well, said Mildred, wait around and see. . . .

A great thunderstorm of sound gushed from the walls. . . .

When it was all over, he felt like a man who had been thrown from a cliff, whirled in a centrifuge

and spat out over a waterfall that fell and fell into emptiness and . . . never quite touched anything.

The thunder faded. The music died.

"There," said Mildred.

And it was indeed remarkable. Something had happened. . . . and you had the impression that

someone had turned on a washing machine or sucked you up in a gigantic vacuum. You drowned

in music and pure cacophony.

Americans are so used to the music and cacophony, they hardly notice it. Bradbury had predicted the Modern Age to that personal a degree, and he understood the angst and insecurity prompting it.