A Feminist Contrarian

SUSAN PINKER: A Feminist Contrarian

I came across the name of Susan Pinker from an interview in the German magazine Der Spiegel, that ran during the last week of September in 2008. Pinker had gained some notoriety in academic circles for her book Sexual Paradox that she published that year. Der Spiegel published its interview with her under the title "Männer sind extremer" (Men are more extreme). A curious thesis: people are extreme; men just more so.

The Spiegel interview includes a photograph of living Nobel-Prize winners, who are nearly all men. Men also do most business start-ups, not just highly-touted IT firms, but also more mundane brick-and-mortar, as well as on-line businesses—something like 89% of the total; women just 11%.

The article also includes a photo of a typical, overcrowded American prison, where hardened criminals are nearly all males. At any given time, Pinker estimates, 89% of all offenders are male. The female component is just 11%. All the mass-murderers of the modern era—Saddam, Hitler, Stalin, Tojo, Idi Amin, Mao, plus the minor players like the Serbian ethnic-cleaners, the Pashas who led the murders of a quarter-million Turkish-Armenians, as well as the African genocides in Nigeria and Ruwanda—are males.

The difference goes much deeper than that. I have witnessed many fist-fights during my lifetime and have participated in two or three myself. Most boys can tolerate five minutes of yelling at each other, then they will settle the matter with their fists, and if that doesn't work, they might go for a gun or a blunt object. Boys typically store up their memories of a hurt and wait for an opportunity to dish out some payback, and they may wait years for the chance.

Men have a sense-of-self carved in stone. They know who they are; and if their thing is crime or violence, they will pursue that course compulsively for the remainder of ther lives. They may act remorseful of their crimes, but are mostly remorseful when they get caught. They will act remorseful if it helps them get out of jail sooner. After that, they will follow their natural bent again. Recidivism for male ex-cons perplexes and disappoints social workers. They find boys hard to reform.

Pinker says that men excel higher and hit the skids harder. Boys race motorcycles on a highway without a helmet, if they can get away with it, climb the highest mountain by taking the riskiest route, and brag shamelessly about their derring-do. They push the envelope relentlessly. None of this should surprise anyone who has a connection to the real world. Why Pinker's thesis has received so much negative press bewilders me. Even her interview with Der Spiegel, hosted by two of Spiegel's female editors, was testy and contentious.

Some males actually test both extremes—criminality and law enforcement. I guess it makes them better cops to have worked both sides:

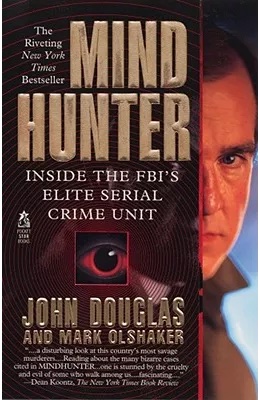

FBI Agent John Douglas gained some notoriety in the mid-1990s when he published a landmark book about criminal-profiling titled Mindhunter. For most of his career, he worked in a division of the FBI called Behavioral Sciences. He could have led the FBI's public-relations department just as easily. Douglas is erudite, charming, and a consumate professional. During college, however, he raised hell, with no sense of the consequences and little personal direction.

Mindhunter recounts some of his wilder exploits—purchasing alcohol as a minor and felony-eluding. He shacked up with a woman at a hotel and had to square off with her husband, who yelled through the door, "Sandy, I know you're in there!" And squaring off with another serviceman in the boxing ring, while in the Air Force. They ended up "beating the holy hell out of each other." The fight broke his nose for the third time, Douglas recalls.

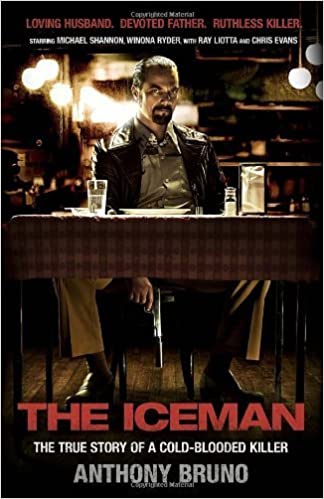

The ATF agent Dominick Polifrone appears in another book, The Iceman, tells the story of the infamous Richard Kuklinski, a hit-man for the Mob. To catch him, law enforcement sent one of its best men, Polifrone. Polifrone had a youth much like Douglas's. Anthony Bruno, author of Ice Man, writes that Polifrone spent his "sophomore year trashing bars on Friday nights and spending the night in jail."

But a police sergeant recognized Polifrone's innate talents and suggested he change his major to law enforcement. The sergeant guessed there wasn't enough mustard in the jar for this hotdog—just the man they wanted to handle really hairy assignments, like taking down the Ice Man.

Additionally, most of the people who commit suicide each year are guys. They go off the deep-end after spend too much time alone in a spiritual wilderness, sorting out personal problems. I don't recommend the solitary approach, because you can't get any input from others; but boys prefer it that way. The call of the wild awakens in them as they turn 12 or 13 and drives them into the forest to hang out with other lone wolves, even if they lack the maturity to live a life apart from their parents.

Pinker's research should not surprise anyone. But so much propaganda obfuscates the truth about men and women, her decision to go public with it brings a lot of attention and criticism down on her. The critics may cause some to doubt her conclusions; but all Pinker really does is confirm what anyone with an open mind and interaction with other people already knows from first-hand experience.

That so many women reject the conclusions of a contrarian-professional bothers me a lot. They should hold onto their horses and maintain some skepticism, if not a cynical eye, of media outlets that try to butter them up with an expansive self-definition that doesn't hold water. Trying to keep it from leaking causes a defensive shift in relation to information or experience that challenges it.

Pinker's Book: Sexual Paradox

Pinker introduces Sexual Paradox on page one with a clever question: "Why can't a woman be more like a man?" She explains that the question comes from the musical My Fair Lady, composed by Alan Lerner and Frederick Loewe in 1956, and made into a famous movie starring Rex Harrison and Audrey Hepburn in 1964.

I listened to bits of it on YouTube and found it not merely old-fashioned but bizarre. Henry Higgins complains about Liza Doolittle. He has done so much for her, and she is not grateful to him. She just mopes:

Why can't a woman be more like a man. Men are so honest, so thoroughly

square. . . . Why can't a woman learn to use her head? Why must a woman

do what her mother did? Why don't they grow up and act like their father

instead?

Higgins speaks his lines in rhyme, and the cadence reminds me of the Wizard of Oz. Watching this prissy, unsexed man, played by Rex Harrison, turned me off. He looks seedy, with a hidden bottle of cheap whiskey in his pocket.

Lerner and Loewe derived their musical from the play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw, which became a famous film in its own right in 1935, starring Leslie Howard and Wendy Hiller. Pinker notes that the play has an interesting plot-line, not explored so much in the musical: Can Professor Higgins coach a dirt-poor, uneducated flower-girl and pass her off as a duchess?

Shaw makes a point in his play, that social stratification depends on social-constructs, training people to act a certain way—not on their personal character. Feminists see womanhood itself as a social-construct, based on how men define them. They want to make the feminist selfhood serve as the norm for women; but it is an expansive self-definition that may leak, if nudged too often. What can they do except substitute one dictatorial social-construct for another?

I took a break from writing this post, logged onto YouTube again, and listened to the song "I Enjoy Being a Girl" from the 1961 movie-nusical The Flower Drum Song. Flower is a cultural hybrid based on the 1957 novel by the Chinese-American Chin Yang Lee and turned into a musical by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein in 1958—all of them guys, in other words. Critics described the movie as an "opulent" production, the first that employed an all-Asian cast.

Pinker recalls the feminist reaction to the male-dominated culture during her youth: "Women were conditioned to have the characteristics of a castrate." Only if "women rejected their conditioned roles by refusing to be men's handmaids . . . dumped their female personae, and took on men's roles, would they truly be equal."

Negative stereotypes set feminists off more than anything, Pinker remembered. When the children's puppet program Sesame Street added Miss Piggy to the cast, the only female puppet, feminists reacted indignantly. Pinker said they worried that "girl-type features would play into stereotypes," the Cookie Monster as anorexic or bulimic, for instance.

Plenty of males groused over Lerner and Loewe's characterization of Dr. Doolittle, at the way it played into feminist stereotypes about chauvinists. Just the few minutes of watching Rex Harrison turned me off too, even as I reflect on how many guys whom I have known behaved like him. A freedom-loving, intelligent culture offers negative models of ourselves, and the public laughs at them, and at themselves. That a book or a movie can criticize with humor and make money in a competitive society should get respect rather than criticism. The negative characters dissuade us from behaving like them. We all accept that.

Perhaps Andrew Carnegie, J.D. Rockefeller, Bill Gates, and Steve Jobs would like control what we see on TV and the cinema, but they cann't. Movies show plenty of negative characterizations of industrial robber barons. A free society allows it, and the TV and movies make money showing them. So why should we make an exception for feminists? Why allow only positive representations? Why force on the public a lifestyle that works fine in theory, but not so well in practice?

Once again, I just wonder how these people expect to inculcate the population with this foolishness. Common everyday experience tell us we have to make a judgment-call about each individual's abilities—not rely on some all-encompassing definition. A thinking person understands that sexual roles and the configuration of relationships depend on many personal factors. Marrieds set up their protected areas, rely on each other according to their needs, with their own in-house support system.

Business enterprises base their decisions on prospective employees by the parameters peculiar to them: reliability, performance, speed, social skills, and personal judgment, not the sex of the applicant. A business alone should make decisions about the kind of person they want, not legislators and disgruntled feminists.

But Pinker writes that the feminist rhetoric convinced her at first. Her book reads as a sort of Bildungsroman—learning first the theories, then hard experience: "I was sure that a woman could do any job a man could." She read Simone do Beauvoir's book The Second Sex and believed that de Beauvoir "had it all laid out. Biology was not destiny." She quotes de Beauvoir: "One is not born, but rather, becomes a woman." Pinker says she believed "There was no such thing as a maternal instinct. Humans were not like animals. We were above all that."

Now Pinker believes that "there are more male outliers—and more 'normal' women overall." But her research ran into problems from feminists. A lot of women did not simply disagree with her research on sexual differences. They did not want to hear about it, period. When others talked about it, they caught hell:

Sex differences . . . was one of the issues that sank the former president of Harvard

University, Larry Summers. . . . Summers had made a speech to a science and

engineering diversity conference on the origin of sex differences. . . . His remarks

launched more than a thousand articles in the press, sparked a year of bitter dissent

at Harvard. . . . By 2006, he was forced out.

Pinker addresses the same issues in her book and received a similar reaction, namely that feminists could not handle sex-difference discussions. They stick with their view that men and women are the same; sex differences are a social construct; they sink or swim with this view. Pinker relates a typical reaction in her book:

When I asked a female social scientist why she thought successful women might be

making different occupational choices from men, she burst out angrily, 'Not that,

again!' I naively asked, 'Not what, again?' 'Not that choice thing, again.' I had

unwittingly touch a sore spot.

Pinker goes on that "a chill had settled on many researchers' willingness to talk about their work." Who can blame them? When Pinker started interviewing subjects for her book, she found that "the chill" had affected them too.

The interviews with the men and women took on a self-reflexive quality, as all the

women asked me to give them pseudonyms and the majority of the so-called fragile

men insisted that I use their real names. . . . Three of the high-achieving women

subsequently had second thoughts about participating—even with pseudonyms and

a change of costume and hair color.

"The chill" in this context really means a lockdown on connected persons' wish to air their contrary views. No one wants to end up like Lawrence Summers, fighting with feminists to hold onto his job. The need to hold this line against dissent remains one of the principal downsides of feminism as most people know it.