A Nation of Shopkeepers

A Nation of Shopkeepers

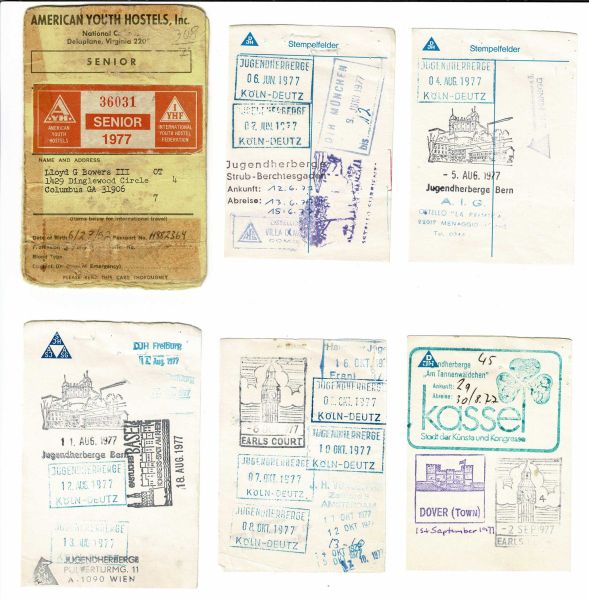

After college, I started working and lived fairly quietly for 18 months, worked hard, started a savings-account, and learned German in the evening from an old Austrian widow. I already knew I wanted to go to Europe, and I intended to stay there for a while. After 18 months, I felt I had saved enough and quit work. I flew to Frankfurt-Main Airport in Germany, aboard a military charter, and stayed with relatives in the military who lived near there.

For five months, starting in late-May, I travelled all over Europe with a Eur-rail pass and a Youth-Hostel membership card. Every evening, I checked in at the local youth-hostel. The wardens added my name to the registry, assigned me a bed, and stamped and dated my entry and departure dates. The hostels provided safe, supervised accomodations. On one occasion, the warden joined a group of hostellers at a pub.

Every day presented an opportunity to meet people my age from other countries. We ate meals in a common-area, on tables that sat six to eight people, and slept in large rooms with perhaps fifteen beds to a room. Many of them were university students on holiday and spoke English well. When I looked up the Earl's Court Road Youth Hostel on-line, it looked unchanged from the time I stayed there.

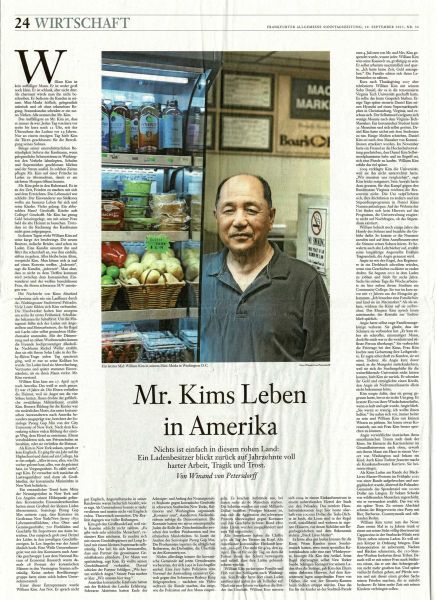

During the day, I was on my own. I spent whole days in the National Gallery, the Tate Gallery, or the British Museum, whose front-steps have the distinction for Marxists, as the place where Karl Marx wrote Das Kapital. I ate breakfast at the Youth Hostel, but lunch I had to manage by myself. Luckily, I found a small grocery store on the other side of Earl's Court Road, which Britons call an "off-license," meaning that you can purchase alcohol that you consume off the premises. Lunch was pretty basic: tinned sardines on rye-crisps, a pork-pie, or baguette and cheese.

I liked London so much, I spent more than a month just knocking around. The longer I stayed in London, the more I noticed that Asians staffed and ran things like off-licenses, the McDonalds, the local Marks and Spencer outlets, and cheap hotels. I remember sitting in a hotel lobby drinking tea, while at another table, the hotel's Asian owner discussed with his solicitor his plan to buy another hotel.

Immigrants play a similar role in this country. When I was a college student at Furman, I remember that Greeks ran all the greasy-spoon type restaurants. In the 1980s, Chinese restaurants sprang up on nearly every important street. Indians ran all the cheap hotels. An old man tended to maintenance, while the women cleaned the rooms. A thirty-ish man checked in guests, while his wife tended to the accounts. In the evening, the children sat at a table and did their homework. Since then, another wave of immigrants has arrived from Central and Southern America. We find Hispanic restaurants on nearly every street. Immigrant ownership of businesses in this country amazes me.

Adam Smith used the phrase "nation of shopkeepers" in his writing. Napoleon also described the British grudgingly as a nation of shopkeepers. The ethos of shopkeeping remains the same in free societies. It remains as true today, as it did in the days of Smith and Napoleon. You can immigrate to a freedom-loving country and start a business with a minimum of hassle. For some reason, only the immigrant-outsiders want to exploit this freedom. Native Britons and Americans become too socialized to stand apart.