A Special Teacher

A Special Teacher

I remember my childhood pretty well—a smug, indolent kid who spent long Summer days in front of a TV, munching on Butterfingers and Snickers bars, with few big ideas about anything. As time went on, wild hormones pushed me forward, more or less against my will. But hormones can only go so far in maturing a person. Something else has to defeat the child's passive-aggression and spur him to want something more.

Many factors provided this spur in my case—which I won't go into here. I only want to talk about one special person, Paul Mulkey. He taught me English in seventh and eighth grade, and awakened in me the desire to write. He did that by reading to us in class. We could tell he enjoyed the stories, even if we didn't. I don't think most teachers would do that. They can't spend the class-time reading to their classes, even in a private school. The teachers teach the assigned syllabus, and students basically regurgitate the syllabus for a test.

Paul Mulkey, middle left Grinning classmate, Jane Ferguson behind him.

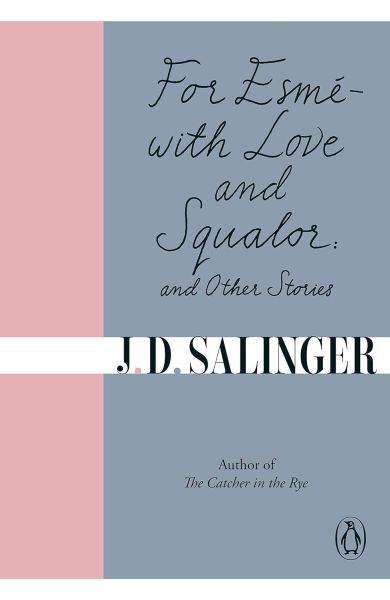

I detect in Paul Mulkey the heart of a frustrated writer. He read to us from works that he—Paul the writer—liked. I remember most of them: "Ransom of Red Chief," by O. Henry, "For Esmé—with Love and Squalor," by J. D. Salinger, and "The Catbird Seat," by James Thurber. I believe he also read to us from "The Laughing Man" by Salinger and "Mammon versus the Archer" by O. Henry. We wouldn't have found these stories in Junior Scholastic magazine, a public school, nor even our cash-strapped private school. The adult situations and themes would have precluded that.

I'll start with "For Esmé—with Love and Squalor," the story by Salinger that appealed to me most. An American soldier narrates the story. In 1944, he drinks tea in a café in England and says that he waits for his unit to ship out at the start of the invasion of France, known as "D-day," June 6th, 1944. He reads distractedly, taking note of the other people in the café, until "Esmé," a thirteen-year-old English girl speaks to him.

Esmé mentions that he drinks tea, as if tea gives him a certain kinship with Britons. She asks him about his role in the impending invasion of France and adds that both of her parents have died as a result of the War, her mother during the London Blitz, her father in North Africa. She speaks to him, she says, because he has a sensitive face and looks lonely. Before Esmé leaves, she and the narrator exchange some contact info, and she then leaves the café.

The story's narrator starts the second-half of the story in second-person, as "Sergeant X," a soldier with all the signs of shell-shock. X cannot sleep, chain-smokes, and carries on distracted, pointless conversations with his tent-mate, "Corporel Z," until Z cannot tolerate his bullshitting anymore and yells at him, "Can't you be sincere?"

Without saying a word, X vomits into a waste-basket. Z cannot comprehend what has happened and excuses himself. Left alone, X studies a stack of unopened mail addressed to him that he finds too challenging to open. Anyone from the insensitive, uncaring outer-world cannot possibly understand how the shell-shock thwarts X's sense of intentionality and direction.

He sees a parcel with an accumulation of postmarks that indicate the parcel has lagged behind X for several disheartening weeks, never able to keep up with the advances of X's Army unit. X opens the parcel and finds a man's wristwatch. Esmé did not forget him and has sent onward her late father's wristwatch and an enclosed letter, where she observes that the watch is "shock-proof."

X feels unbearably sleepy. He has not slept for such a long time, he notices the change right away. He can barely stay awake long enough to assess what has happened to him. Esmé worried, with her precocious vocabulary, whether X would survive the War with his "faculties" intact. X tells her in a fantasy conversation that a really sleepy man will survive with his "f-a-c-u-l-t-i-e-s" intact.

To say that "Esmé" instructs a reader, or teaches its reader valuable lessons about life—the healing power of love, for instance—demeans or depersonalizes the story. It doesn't really pay to analyze it that closely, only to say that the interaction of the characters and the gift of the watch touched me deeply—this little girl's caring for an absolute stranger about to face the greatest peril of his life—sort of haunted Paul Mulkey's 13-year-old students.

RIP, Paul Mulkey, Dalton, Georgia, husband of Cheryl, father of two, grandfather of five.