Aesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables

Of course, I have heard about Aesop's Fables all my life, without knowing much about them. At the beginning of the new millenium, that changed. I read about a construction crew in my great-great-grandfather's hometown in Germany, Erfurt, that accidently dug up a treasure-trove from 1300 a.D. The construction workers turned it over to archeologists in Erfurt.

In the trove, archeologists found silver dishes, jewellery, and silver coins. Among the dishes was a type unique to Germany, the Doppelgefäß, two silver goblets with fitted rims, that the owner could stack in a cupboard. In the bottom of each 13th century goblet, archeologists saw etched, enameled art-work obscured by centuries of grime and corrosion.

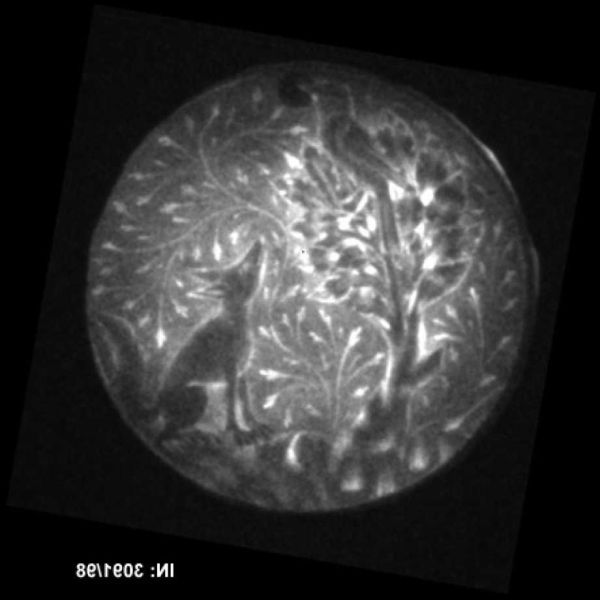

Before they could clean the goblets, the archeologists needed to see what was under the grime; so they x-rayed the base of the goblets and saw enameled images of a fox talking to a raptor, who had captured the fox's kit and eaten it. The enraged fox set the raptor's tree on fire. When its chicks fell from their nest, the fox ate them.

The archeologists later explained that the images represented one of Aesop's Fables, "The Fox and the Eagle." As far as I know, the earliest manuscript of Aesop's Fables dates from around 225 a.D. But truthfully, historians do not know who Aesop was, or if he even existed as a real person, or as a composite of several writers of fables who all date from Antiquity.

Several fables stand out as cultural icons by their own strength, although scholars attribute them to Aesop: "The Goose that Laid the Golden Egg," "The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing," and "The Fox and the Grapes." The fables—parables, really—have a common-sense, psychological depth and insight that endures and can stand its own, among modern, literary masterworks. People can use them as a sort of touchstone, as a philosophical bed-rock that can undergird the culture.

Then, I read that Aesop composed another fable about frogs who lived in a pond and pleaded with Zeus, the Greek god—called Jupiter in Roman mythology—to send them a ruler; so Zeus sent them "King Log." I recognized this story from the British mini-series I, Claudius, which premiered on Public Television in 1976 and has run many times since. My reader can find all of the episodes on YouTube.

The frogs in Frogland had grown tired of governing themselves, and croaked in a bored manner for a government that would entertain them with pomp and circumstance, and "rule them in a way, to make them know they were being ruled." Jupiter sent them a big log that lay in the water near the shore and called it "King Log".

The frogs remarked how "tame and peaceable" King Log was, but the frogs mostly used King Log as a meeting place where they could complain about it; so Jupiter took out King Log and gave the frogs a King Stork instead; but the stork ate frogs for a living. They took to complaining to Jupiter about it, but Jupiter said they would just have to live with the circumstances.

One can take exception to the political systems Jupiter offers the frogs, but I see the insight here as a recognition that we either learn how to govern ourselves, or take a chance by letting someone else govern us, where we risk being eaten.