Alternatives for Black Social-Planners

Stretch your tent curtains wide!

Do not hold back!

Lengthen your cords!

Strengthen your stakes!

Isaiah, 54:2

The Qualities of a Leader

The ability of people in a nation to set high goals for themselves and to reach them depends a lot on leadership. The leadership class has to institute a framework for progress. It has to study a problem, supply a solution, and direct it. People rely on their leaders, both for forward-moving measures, and a justification of those measures. The leaders do not rely soly on their own judgment. They also set up documentary parameters, that political people usually call a "constitution," that will continue to direct the nation after they are gone. The constitution teaches the people how to act like citizens by giving them a value system and a mindset that guides their actions.

The word "leader" needs no explanation. A genuine leader leads people. He behaves like a cavalry officer at the front of his regiment. He gives the command "Forward, ho!" and the regiment moves out. He behaves like the trail-boss at the head of the wagon-train leading American settlers out west. The word "forward" speaks for itself. At sea, the ship's watch calls out "Land, ho!" when he sights land. The word "ho" means to "Look ahead and pay attention!"

Sometimes the leader has to soothe the hurt feelings of people in times of defeat and to give them the resolve to keep moving forward, to restore their courage, and to renew their vision of the future. Sometimes the very words of a leader can remain in the everyday vocabulary of people, long after the leader himself has passed on.

President Roosevelt: "Yesterday, December 7th, 1941—a day which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan."

Prime Minister Churchill: "If the (British) Empire lasts a thousand years, men will say 'This was their finest hour.'"

President Truman: "The buck stops here."

President Reagan: "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall."

Martin Luther King: "I look forward to a day when people will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character."

Sometimes a good leader has to stand up to his own people. He has to tell them truths that they do not want to hear, and risk retaliation for saying them. If one single document expresses the terms of leadership, it has to be the poem "If" by Rudyard Kipling:

If you can keep your head when all about you/

are losing theirs and blaming it on you/

if you can trust yourself when all men doubt you/

but make allowance for their doubting too. . . .

If you can bear to hear the truth you've spoken/

twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools/

or watch the things you gave your life to, broken/

and stoop and build 'em up with worn-out tools. . . .

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew/

to serve your turn long after they are gone/

and so hold on when there is nothing in you/

except the Will which says to them, "Hold on!"

The leader has to behave like Moses. He has to keep the people aware of the Promised Land and make them hopeful about the future. He has to delegate the minutiae of everyday life and reserve a place in his head for the "big picture." He has to tell people, "Your sense of the possibilities is too small. Enlarge the area of your tent." He also has to believe in himself, in order to protect his vision from those who want to usurp it.

Black social-planners who want to create their own country should acknowledge that blacks with foreign ancestry have an advantage over the American blacks. Foreign ancestray gives them a position apart from the psychological inertia that afflicts American blacks, because their ancestors lived in independent nations. The American status quo does not have a hold on them. They have a native sense of the benefits of nationhood—people like Marcus Garvey, former Secretary of State Colin Powell, and former President Barack Obama. Their home-countries may have been poor, but they understand how the world confers privileges on passport-holders and how it respects a national consciousness.

Eric Hoffer explains the national consciousness in his book True Believer:

Hitler had managed to exterminate six million Jews without meeting serious resistance.

It should not be too difficult to handle the 600,000 Jews in Palestine. Yet they found

that the Jews in Palestine, however recently arrived, were a formidable enemy: reckless,

stubborn, and resourceful. The Jew in Europe faced his enemies alone, an isolated

individual. . . . In Palestine, he felt himself . . . a member of an eternal race, with an

immemorable past behind it and a breathtaking future ahead.

This should appeal especially to Black-Americans, who likewise have faced their enemies alone. Nationhood offers membership in an eternal race, the ability to put a degraded past behind them and anticipate "a breathtaking future ahead." They can only achieve nationhood if they can identify leadership qualities in people, so they can recognize potential leaders on sight.

This challenge of sorting out the good leaders from the bad will test the judgment of a people. The world has more false leaders as it has false prophets or quack doctors. The search for a leader involves delving through his public statements and patterns of behavior for criminal or self-serving intentions. The longer you look at some candidates, they will start to look like criminal suspects rather than aspiring leaders.

The Leadership Class

The unresolved conflict of Black-Americans in their relations with the whites points unequivocally to an absence of competent leadership. Genuine leaders lead, whether they command soldiers in the field of battle, whether they take charge of civilians fleeing a natural disaster, or when they mediate between feuding civilians on the home-front. A leader utters the memorable words, "Forward, Ho!" The word "forward" speaks for itself. The word "ho" reminds us, "Look ahead and pay attention!" Our leaders give us our marching orders.

In general, the black community lacks this kind of leadership. Black leaders browbeat the whites, act menacingly and outraged, but they hang back and let the whites provide the solutions. For some reason, the problems in the black community keep coming back, and the leaders, limited by their view of the situation and their reliance on the whites, keep making the same demands over and over. So why, I have to ask, are we still governing these angry, defiant black people? Wouldn't they prefer their own country? If they had a nation, they could initiate the problem-solving. They could make the United States Congress take up the issue of nationhood in session. The Congress would vote to give the blacks their own nation—with real estate cut right out of the US.

The current black leadership would likely be shocked: "How the hell do you expect to just kick out a whole population of people? This is our country, too!" Such a response just stinks of dependence and helplessness. Deep down, the blacks know they are selling themselves short.

Each rejection of an independent life dumbs down their estimation of themselves and their ability to succeed in a free society. The lower expectations and self-image create a sort of personal vacuum in their lives. Violence and disorder fill that vacuum. Educators and social scientists know most of this already, but the fear of censure constrains them from going public with it.

Any serious study of black-on-black violence will have to start with the loss of self-respect and the declining self-image. The loss of faith fuels a stew of angry emotions: "Epaminondas! You ain't got de sense you was born wit'!" Epaminondas and his Auntie gives black people the spooky feeling they are reading about themselves. Many black males displace those negative feelings violently on other blacks.

I may be wrong on individual details, but I know something systemic makes black males kill each other. It happens too often to be just neighborhood beefs or gang affiliation. Many blacks have seen those negative emotions up close, so they must know a lot about them but seldom talk about them, at least for the public's ears. Many educated whites have some understanding about them but never say anything. They never say what those negative emotions are, except to lament, "Why, o why are so many young blacks murdering each other?" The emotional cocktail in the black psyche remains something they cannot communicate.

The amount of deception swirling around Black Lives Matter really bothers me. The one group that routinely disregards the worth of black lives is the blacks themselves. Their leaders rarely draw any attention to this fact, rarely make a concerted effort to understand the causes. All they do is shroud the causes in sympathetic photo-ops and condolences, and blame the whites. In Chicago, homicides of blacks account for 79% of the total. Other cities have recorded similar figures in 2019 and 2020 homicide statistics.

Why does no one—civil-rights leaders, journalists, or politicians—go public with constructive and coordinated actions at the government or foundation level? Maybe because they would have to start with an analysis of the causes. An intrusion into the personal concerns of black people would make black people uncomfortable; so they have to tolerate the slaughter, even while they protest it. If they cannot dig in themselves for solutions, then how do they propose to resolve the problem? Free pizza and sports equipment? It's laughable.

I Hate You! Don't Leave Me!

Years ago, I had a girlfriend who made me feel that I could not do anything right. It was the worst year in my life. She criticized me harshly for every little oversight and convinced herself that I did not have her best interests at heart. She expressed her doubts about me so frequently, I had to ask myself if was I the right person for her?

She convinced herself that I meant to ridicule her. Again and again, our conversations had to stop on a dime while she took exception to something I said. She did this so often, I was too afraid to say anything. Instead of welcoming that, however, she insisted that I tell her what I was thinking. It never worked. When I spoke, my words offended her so often, she began to launch pre-emptive jibes, as revenge.

Eventually, she drew up a sort of ultimatum and handed it to me in the morning before she left for work. In it, she said she no longer trusted me to care for her. For that reason, she needed to break up with me. She had deep doubts about my real feelings toward her. Often I had behaved thoughtlessly towards her. She had given me her love, and I was wasting it.

That evening, when she came home, I told her that I agreed to a break-up. Stunned and exasperated, she started crying and told me she hadn't intended anything of the kind. "Why do you want to break up with me, Lloyd? Tell me one good reason why we should break up."

I wanted to tell her that I thought she wanted to break up with me. I had given our relationship my all, and it hadn't worked; so the best thing we could do was to break up, but before I could say more, she just overrode me and told me how gutless and self-centered I was. She turned self-pitying and browbeat me into submission: only cowards and wimps give up so easily.

I felt like I was damned if I did and damned if I didn't. My shame and confusion just squeezed me in a vise. If only I could explain to her why I wanted out, she might understand. Instead, she argued me to a standstill, her grief growing more shrill the longer I defended myself. I had to let her have the last word, even if it left the matter unresolved.

That she had such extreme opposing feelings—a deep need for me, juxtaposed with an equally deep need to rid herself of me—just left me spinning. I gave up resisting her arguments, but giving up did not bring any respite, either. She didn't want me to give up. She upbraided me for my defeatism and told me I had to argue my point-of-view. The entire set-up of this scene troubled me.

Months later, thoroughly demoralized, I told my girlfriend I had to get out of there. I was at the end of my tether. Predictably, she argued my decision bitterly: how could I betray her so thoughtlessly? She had tried so hard to make me happy. I felt like a shit-heel loser, a spoiled little boy who did not know how to care for another person. How could I be so cruel? Like any truculent two-year-old, red in the face from weeping, nothing could make her happy.

By that time, I knew not to let her draw me into an argument. I could never have convinced her with arguments. She would only brush away my arguments and counter that it was cruel of me to want to leave—even though staying condemned us to the same unsettled state we had endured for too long already. I just gathered up my belongings and moved out, totally spent.

At the advice of a friend, I went to see a therapist. In a session with her, I told her that two dominant emotions controlled my girlfriend's actions toward me: hate and need. She hated me because I tried to dominate her and because I was in her face all the time. She cried bitterly that I neglected her and wondered if I really loved her. She felt disgust and grief when I shielded myself from her. The only way to save my sanity was to leave, with no resolution of anything.

With a knowing smile, the therapist reached across her desk and handed me a paperback-book titled I Hate You! Don't Leave Me! published in 1989 by Doctors Kreisman and Straus. I nearly fell out of my chair. The authors write that their patients "cannot see the big picture" well enough to move forward. One moment, they want someone to take care of them; the next moment, they suspect even their therapists of trying to control them. They carom back and forth like this for days—making one contradictory demand after another—never aware that they are doing it. One moment, they trust the therapist as a child would. The next moment, they fill up with paranoia and tell the therapist off brutally.

The scenario reminds me of an infant going through Terrible-Twos. He wants to be his own man and not have mommy and daddy telling what to do. At the same time, he scolds mommy and daddy for wanting to neglect him. The infant never catches on that he wants contradictory things at the same time. He may act like this for months, never aware that two stages of consciousness inhabit his two-year-old brain simultaneously, like a split-personality; but in the end, the clingy, infantile self yields to a new stage, a child who wants to explore and assert itself.

People like my former girlfriend never quite complete that transition. They can never gain enough independence without wishing to rely on a parental figure. Their tenuous grasp of selfhood makes them too defensive to allow them to merge with a lover. The loss of personal space scares them so badly, they have persistent problems with continuous intimacy, and relate to a partner by pushing and pulling all the time. Kreisman and Straus said their patients exhibit a "demanding dependence," even with a therapist.

The authors had such good intuition about my former girlfriend, they may have known her as a patient. Needless to say, the revelations floored me. Several times, I complained to my girlfriend that she jerked me around—one moment wanting me closer, the next complaining that I was crowding her. "I believe every person needs his or her personal space." When I backed off, she looked at me with fright: "Why are you so distant to me?"

Then Kreisman and Straus dropped the biggest bomb of all: Welfare-oriented societies in the West have a huge influence on the way people develop and live. The authors quote social scientist James Masterson who "notes that governments with extensive social-welfare systems . . . promote a social dependency that discourages autonomy and increases borderline and sociopathic behaviors among the citizenry."

I nearly fell out of the chair again. This went way beyond a problem with a dysfunctional girlfriend. Kreisman and Straus give a fairly important warning about American society, and it lands squarely on black Americans, who cannot reach the individuation stage. They hang back and let the whites take care of them, rather than risk the responsibility of nationhood. They have to accept the loss of personal initiative and self-respect as the cost of hanging back.

The blacks need to reevaluate the high cost of gaining security through affiliation with the whites, inasmuch as affiliation leaves them personally insecure and conflicted. Maybe the whites will stop taking care of them. Maybe they will re-enslave the poor black people all over again—damned if we do, damned if we don't.

Who Are the Black Leaders?

All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that

right, they freely determine their political status and freely pursue

their economic, social and cultural development.

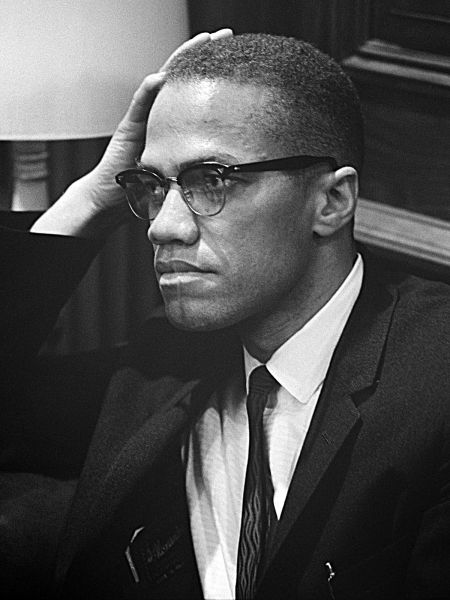

Malcolm X before the United Nations

General Assembly, December 10, 1966

To recapitulate the opening theme of this post, let me say again that the leadership class in a nation gives the citizenry its sense of collective identity. It initiates solutions to problems. It also prioritizes problem-solving, tackling the most pressing problems first. The leadership class also has to keep its ears to the ground to pick up whispers of citizens' stress or disappointment, then backtrack away from their goals, so as to not overtask the citizenry. The leaders must also maintain an awareness of the nation's constitutional parameters, to keep it on-track, steering the public toward recogition of those parameters.

Several groups of people constitute black leadership: politicians, organizers, academicians, and athletes. Missing from this list are business-leaders. There simply aren't many black business-leaders, which limits their sense of the opportunities for wealth and power. Even so, the writers interest me the most, since they define the human culture. The other groups get their talking-points, their justification, from the writers. Sometimes the reputation of a writer promotes him to "philosopher" status, inasmuch as he loves (philos) knowledge (sophia). He may find it a Quixotic role, inasmuch as other people doubt he has his feet on the ground.

He may find that he achieves about as much success and satisfaction as the mythological character Sisyphus who tries to roll a stone up the hill, only to watch it roll down again. No matter how hard he tries, the stone always rolls back down the hill. The philosopher tries to turn his failure into success by making a principle of his failures. Among other things, he has to explain logically that mankind behaves illogically, and that our chaotic world has at its core a sense of order—divine, meteorological, or just dumb luck. The philosophy professors I knew during college smoked like chimneys. They had a rough life.

In the photo, Malcolm X appears to ponder his fate as a philosopher. His comment about self-determination and political status did not resonate well in the black public, since they preferred to stick with the whites. As a spokesman, as a philosopher, he may have had to backtrack away from nationhood, if the government offered it to him, since the blacks had already rejected it for him? Like my ex-girlfriend who wanted to leave me, but refused after I had offered to let her go, the blacks will insist on staying with the whites. It says to me that they have lost faith in themsleves and adopted a second-class mindset.

I have had to read so much in preparing this post, I could not cover all the bases, but such evidence as I have seen suggests that Malcolm X did support at least separation from the whites, but whether he wanted a separate nation outside the U.S., or a black enclave inside it, is unclear. He may have wanted the black enclave to serve as the way-station before a return to Africa. Entrenched racism by the whites made him conclude, as another civil-rights leader expressed it, "this black-white thing doesn't work."

Since Malcolm X's assassination in 1963, his life has undergone some revamping in order to bring him in line with the new official view established by people like Cornel West, Michael Dyson, and others—that black-nationalism works better without nationhood. They also did not want to go to Africa because it did not have the modern conveniences that they had already become used to in America.

Or else they had second thoughts about a nation based on Marxist socialism advocated by Malcolm X. They didn't need a rocket scientist to explain to them that a Marxist government only succeeds if it can exploit existing wealth. If a government wants to build highways, bridges, and hospitals after the money runs out, then it will have a problem. Where will a Marxist government get the money to pay for those things—the UN? Blacks in Malcolm X's day must have already known that Germany had tried to divide into two nations with competing economic systems—one Marxist and the other capitalist—and realized that Marxism did not work. So why try it again in Africa or anywhere else?

Besides, Marxism offers Black-Americans just a gussied-up version of a plantation society. Except for government officials, everyone is equal—that is to say, they are all second-class. The blacks of Malcolm X's day could recognize a second-class culture, since they had already lived in one, and did not want to live in another one. In a Marxist society, the sticklers for equality will remind them not to act superior.

If Malcolm X's Marxist economics has its way, then the government will confiscate the wealth of private Americans. Do Marxists realize what will happen next? The stock-market will tank. All of the teachers' and nurses' pension funds, charitable foundations, and college endowments supported by the stock market will collapse to a fraction of their present value.

Why does this happen? The stock market is the most amazing animal—a money machine. It works based on the future prospects of the economy. The wealth that we use today is actually wealth tele-transported from the future. Try to steal it, and it reverts to the future. It says, "Beam me up, Scotty! There's no intelligent life here!" and disappears.

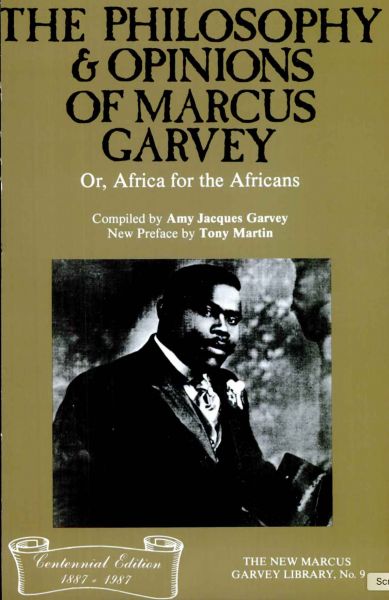

Who Builds Black America, Marcus Garvey . . .

Marcus Garvey is the only "modern" Black-American who has unequivocally advocated a separate nation for blacks. Not surprisingly, he also wanted to replicate the American economy. He wanted a capitalist economic system, which typically offers start-up capital to enterprising business people to finance a new business. Business-owners often pay their investors in stock, so a capitalist economy normally includes a stock market. As a business increases in value, the value of the stock increases in value, too. Everyone else wants to climb on board so that their money will grow as well. Pension funds and college endowments all want to grow their wealth in the stock market,

Garvey wanted to encourage business start-ups with investment. He would tax the wealth generated by commerce to finance improvements to the infrastrructure of the nation. Again, he believed that wealth provided the key to a successful, black nation. Garvey's plan does not surprise me. He grew up in dire poverty in Jamaica and knew how much poverty impacted his life and the people around him. He knew that wealth, if correctly employed, can multiply itself, but a nation can only increase wealth if it remains in private hands.

Garvey boasted that "Black millionaires (are) a possibility." The whites had their Rockefellers and Carnegies. "Why should not Africa give to the world its black Rockefeller?" In another way, he is really asking why blacks shouldn't own wealth? "Now is the chance for every Negro," he continues, "toward a commercial, industrial standard that will make us comparable with the successful business men of other races. . . . All that Africa needs is proper education."

Blacks need to do more than that, unfortunately. They need to resurrect Garvey's market-orientation toward wealth-production. They have lived with a second-class mindset for so long, it has stunted their sense of the possibilities.

So many whites remain childless through their lives, they have lost track of the on-the-job training involved in child-rearing. If parents overprotect an infant, the infant learns to behave passively and dependently from the cradle onwards. The infant will likely rebel against the controlling regimen, without really knowing why, since its upbringing lacks a holistic orientation toward independence and intentionality. "Give the blacks a chance," demands Garvey. "If the Negro is inferior, why circumvent him; why suppress his talent and initiative; why rob him of his independent gifts?" Garvey says he read Booker T. Washington's Up From Slavery, and it led him to ask, "Where is the black man's government. . . . Where is his President, his country, and his ambassador, his army, his navy, his men of affairs?"

Modern American blacks might respond that the whites have already taken care of that problem by instituting quotas. They set aside a minimum number of positions in any field for people of color—including Presidents, ambassadors, and generals. The United States Congress does not actually have a law to that effect. Admitting tokenism to that degree could embarrass them, but everyone knows the government has to set aside positions in every field for minorities.

Quotas free black people from the fear of rejection and makes their inclusion in decision-making a matter of law; but it still represents second-class thinking. The whites' reflexive stepping into the breach stunts the blacks' response to challenges and their ability to self-start anything. Nothing conveys this better than the near-absence of black business start-ups, which figure importantly in Garvey's self-improvement plan.

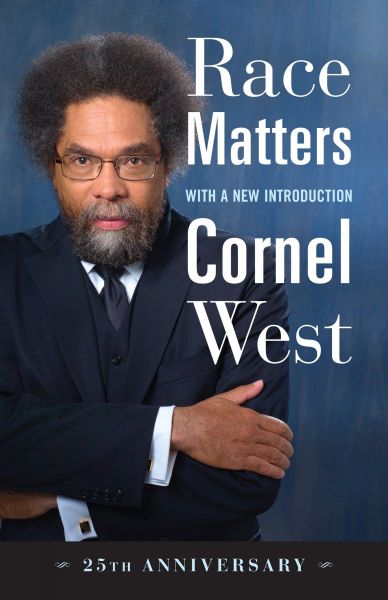

. . . Or Cornel West?

Modern Black-America hears mostly from noisy neo-Marxists like Cornel West. Since Marxism can only exploit existing wealth, not create it, the blacks remain dependent on the whites to create it. The dependence has become status quo. It maintains the second-class mindset that dumbs down their personal expectations. Ask someone like Professor West how to remedy this situation, and he will invariably answer that the whites need to do more for the blacks. Such routine intervention has become the norm, and casts the relationship into a paternalistic mode, from which the blacks cannot break free.

But West makes a case for Marxism stridently: "Industrial capitalism . . . boasted of its overt racist practices such as its Jim Crowism . . . its exclusionary immigration laws . . . and . . . containment of Mexican and indigenous people. . . . Multinational corporate capitalism, with its bankrupt and authoritarian-like state and administrative-intensive workforce, turns its pricipal racist ammunition on the black and brown."

In another diatribe, West continues his rant. "The most brute fact about the American terrain is that the U.S.A. began as a liberal capitalist nation permeated with patriarchal oppression and based, in large part, upon a slave economy."

After such denunciations, one would expect West to want to lead black people out of the racist U.S. and into a new nation that exemplified his wish for equality and Marxism; but he does not do that.

For one thing, like Malcolm X, West would find Black-Americans hesitant to leave the U.S. if they cannot find the modern comforts they are used to.

But this does not stop West from criticizing heatedly: "The repressive state apparatus in American capitalist society jumped at the opportunity to express its contempt for black people. . . . The drug industry, aided and abetted by underground capitalists, invaded black communities. . . ."

This sort of b.s. makes me want to say to him, "Come on, Professor, you're putting us on." The late Manning Marable did not laugh at his antics: "Few black intellectuals today maintain an authentic, organic relationship . . . among working-class and poor people."

The reason, writes Mark David Wood, is "they are, in large measure, 'hand-picked' by white elites and consigned the task of communicating the reality of black life to predominantly white audiences in a way that does not challenge the status quo." West's approach to policymaking stresses gaining power against the whites, rather than gaining independence from the whites. The scenario suggests children trying to gain power against their parents. But as the parents give way, the children scold them for neglecting them and begin to behave more chaotically, needing guidance.

For a Marxist, Professor West has some curious, contrasting elements. He has taught mostly at elite white universities. He feels he has to dress the part in a three-piece suit with an accompanying fob- watch. West's car, he boasts, "is a rather elegant one."

Apropos of that, he faced criticism at Harvard for missing classes, neglecting serious scholarship, and instead spending his time on "economically profitable projects." Black-leadership by West, this suggests, even if the blacks choose to remain part of the U.S., will mean leadership by a man with divided, contradictory loyalties. Compare him to Garvey, even considering Garvey's impoverished beginnings in Jamaica and limited education, and West will lose out. Garvey spoke forcefully and fearlessly throughout his life—campaigning to regain self-respect for blacks through independence and nationhood.

To Their Own Nation

. . . (The slave) said, in answer to further inquiries that there were many free negroes in this region (Rockingham, North Carolina). Some of them were very rich. They bought black folks, he said, and had servants of their own. "You might think, master, dat dey would be good to dar own nation, but dey is not. I will tell de truth, massa . . . and it's a fact, dey is very bad masters, sar. I'd rather be a servant to any man in de world, den to a brack man."

From A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, by Frederick Law Olmsted

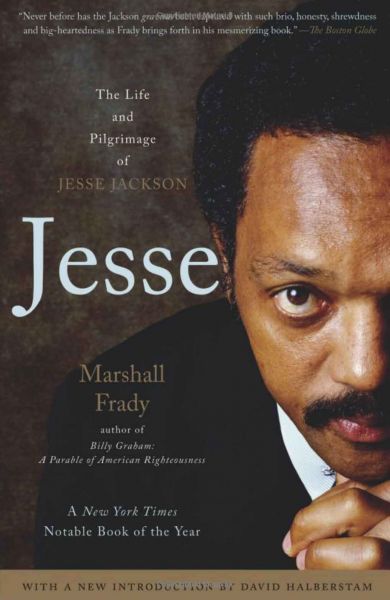

The biggest hindrance to black-nationhood might be mistrust of black leaders. The ambivalence of blacks about their leaders shows up especially well in their feelings about Jesse Jackson. He worked tirelessly for civil rights and black career-opportunities, but when he ran for President in 1988, the most important people who endorsed him were white: future presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, Senator Paul Wellstone, The Nation magazine, and Senator Ernest Hollings.

The Greenville News in Jackson's hometown Greenville S.C. published an article on the presidential campaign he had run and took him to task for his treatment of campaign volunteers. Campaign-manager Preston Love complained that "Jackson had a habit during the 1984 campaign of showing up in a city and blasting local volunteers if preparations were not exactly to his liking." Jackson regularly humliated people publicly, "constantly tell you what you're doing wrong, never what you're doing right."

Again and again, Jackson reveals himself as a fanatical self-promoter, more than a civil rights . Martin Luther King said to him, "If you want to carve out your own niche in society, go ahead, but for God's sake, don't bother me!" After King's assassination, Jackson showed up for an interview in Chicago, 500 miles away, still wearing a sweater with King's blood on it. "It's the same dynamic that took place around Jesus at the crucifixion time," Jackson explained. Everyone wants a relic.

Jackson's brother Noah Robinson asked him about a local volunteer. Why not pay him something? Jackson was not moved: "'Cause he ain't got good sense. He doesn't have the sense to take care of his own affairs."

Later Jackson caused a minor fiasco during a TV interview when he engaged in some trash-talking of his presidential-primary opponent Barack Obama, claiming he would like to castrate Obama. He did not know the mike was still on. Obama for his part accepted Jackson's apology and, for the most part, conducted his presidency with dignity and elegant speech. He carried out his duties as a seasoned official and as a tough, resilient President. With his foreign ancestry, he maitained an independent point of view. Many of my white friends voted for him.

He expressed his toughness, once in a while. On one occasion, he kicked open a door he could have opened as easily by hand. If Black-Americans want real leadership, they need to think in terms of Obama rather than Jackson or West, who serve too much their own egos and appetites. Neither has an intentionality toward nationhood.