An Echo of Theresa

An Echo of Theresa

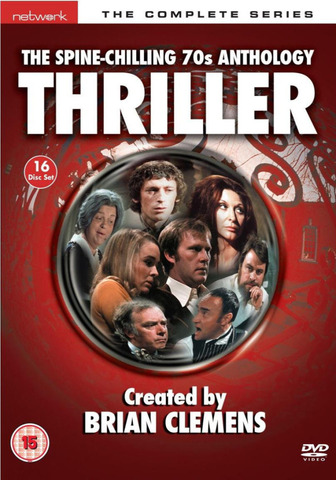

After I finished college at the end of 1975, I returned to my home in Columbus, Georgia, and started working for my father at his livestock-feedmill. While the U.S. endured a lagging reputation and a lackluster economy, I remember a number of innovative, high-end TV shows from Great Britain, among them The Prisoner, The Benny Hill Show, and Monty Python. Some of them originated in the late 60s. There was another series during this period, but I could no longer remember its name and had to look it up on-line. From the few actors and story-lines that I remembered, I came upon the nameThriller, a show that ran for a few years on British TV, before the British exported it to the U.S.

One episode, "An Echo of Theresa," features two American characters, Brad and Suzy Hunter, a married couple visiting London for the first time. They enjoy some vacation-time. while Brad works on a product-line licensing-deal with a British company. He sits over coffee in his hotel room, opens the daily edition of the British newspaper The Times. and stares at it fixedly without reading it. Then, he folds it and tears out one corner, leaving a heart-shaped hole in the middle. Something about the newspaper puts Brad in a kind of trance.

His British counterpart arrives to discuss business, and Brad, casually introduces his wife as "Theresa". Hurt and confused by the suggestion that Brad has multiple wives, Suzy leaves the two men alone. "Women!" Brad scoffs dismissively. Later, Brad tries to explain to Suzy that he does not know what came over him. The viewer can see, however, that Brad has changed in that short time. His good-cheer is now mostly a product of artifice.

Polly Bergin as Suzie, Paul Burke as Brad

Later in the hotel bar, Brad asks a waiter to bring him some cigars—the best he can find. Suzy looks surprised and tells Brad he doesn't smoke. He never has. Brad is sort of beside himself and scolds a waiter for wanting to put ice in his glass of Scotch. He's about to jump out of his skin, and neither of them knows why. Unaccountably, he runs from the hotel and hops into a taxi. Suzy follows him and hears him tell the dazed driver to take him to Manchester Square off Oxford Street. Once again, Brad appears to be in a sort of trance. The driver politely asks if this is the couple's first visit to London. Tthey tell him it is; but when they arrive in Manchester Square, Brad shows evident familiarity with the area.

"Where is the brick building that was here?" he asks the driver. A modern building occupies the site. The taxi-driver looks at him in surprise, "I thought this was your first visit." They tell him it is their first. The driver explains, "Funny, there was a brick building—stood just there."

It rekindles Suzy's worry that Brad has been seeing another woman—possibly Theresa—and that he must have met her on an earlier business trip, while Suzy stayed home with their their baby. Brad insists he has never visited London before.

With Suzy pestering Brad to tell her about Theresa, Brad threatens Suzy. It scares the daylights out of her. He has never done anything like that before; and he just gets worse. He calls for another taxi, without Suzy, and visits another building. He goes inside, stops in front of an apartment and rings the door-bell. When an unknown man opens the door, Brad asks for Theresa. The man answers that there is no Theresa there. Brad has brought a copy of the The Times with him, with the signature hole in it, and leaves it.

When he arrives back at the hotel, he finds Suzy with a private detective. Brad's threatening her was the final straw. With the private detective questioning Brad about everything that has happened, he finally admits that—not only is Theresa his wife, but his own name is really Charles Merrow. He is a British citizen who attended Ferngate College in Hampshire, England. The headmaster was Leslie Cromer.

The private detective calls on Suzy a few days later and tells her that there was a Ferngate College in Hampshire. He pauses and tells the couple to hold onto their hats. The former headmaster was Leslie Cromer. Brad and Suzy look at each other in complete confusion. Then the private detective takes Brad for a ride in another taxi. They wait in a side street and watch a well-to-do man and woman climb into a car, and drive away. "That," the private detective tells him, "is Charles and Theresa Merrow." Brad admits that he does recognize Charles but hasn't a clue where they could have met.

But neither the private detective nor Brad realize that the Merrows are also keeping track of Brad. Their crew descends on Brad and Suzy at their hotel room and carries them off. One member of the crew injects Brad with truth-serum, and Charles Merrow starts interrogating him. Suzy sits next to Brad, bound with rope, She has never heard him talk like this. He served in the U.S. Army in Korea, was captured by the Chinese, and became a POW. He had to submit to brainwashing administered by Soviet agents, who tried to implant an alternate personality. They failed and turned to another POW, namely the present Charles Merrow. This explains how Brad recognized him.

It becomes clear to the viewer that all of Merrow's mannerisms—regarding quality cigars, Scotch without ice, his assertiveness, brashness, and implied sexism—reflect the Soviet brainwashing effort. Brad had resisted it on one level—completely absorbed it on a deeper level; so that when he opened an issue of The Times, it triggered his old alternate identity. He tore the hole in The Times to alert the members of his cell, just as he should have done. Brad began to act out a persona that he had never lived. By the time all this happened, Merrow and his crew had been inactive for twenty years, so the encounter with Brad took them by surprise.

The crew complains that they can no longer handle an issue of this type; but Merrow insists that the interrogation go forward and introduces Brad to Theresa. Theresa holds The Times in Brad's face to maintain the control. The sinister-looking Basil Henson plays Charles, and Meriel Brooke plays Theresa Merrow.

Left to Right: Meriel Brooke, Basil Henson, Paul Burker, and Polly Bergin behind him

I won't give away how the story ends. I was mostly interested how Brad's experience illustrates the concept of "cognitive dissonance," which means essentially the holding of contradictory opinions, beliefs, and presumptions. Cognitive dissonance causes psychological stress, inasmuch as a person naturally wants consistency and single-mindedness.

In his own life, Brad acts like a corporate executive, a man used to supervising networked, corporate personnel. The Charles Merrow persona, on the other hand, acts like the boss in any and every situation. The Soviet profilers and psychologists who brainwashed Brad and Charles concluded that other people would most likely follow a man with ego-strength and a command-mentality.

Wikipedia writes that "In A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957), Leon Festinger proposed that human beings strive for internal consistency to function mentally in the real world. A person who experiences internal inconsistency (like Brad) tends to become psychologically uncomfortable and is motivated to reduce cognitive dissonance."

One important scene in "Echo of Theresa" bears out this point. The private detective asks Brad if he ever visited Vienna. He said no, but the detective told him, "You said you met Theresa in Vienna."

"Yes, we met in Vienna," Brad admitted, again as if in a trance, "in Vienna."

"So you have been to Vienna?"

"No," Brad repeated with nervous insistence, "I have never been to Vienna."

The permutations of this scene are interesting. A person can maintain contradictory views, even if it costs him peace of mind. A person can also hold two different identities, even if it causes him a great deal of stress. That is the reason we strive for consistency. A stable personhood depends on congruence in the sum of his views—his point-of-view.

American disunity involves a lot of cognitive dissonance. All you need is a few outlier egotists who have nothing better to do than to browbeat the people around them, until they agree that they have never been to Vienna, even if they met Theresa there. We give different answers to different people, depending on how much pressure they exert on us. We hate them for bullying us, even when we go along with it. If we want to talk truthfully about American psychological discomfort, we must take this into account.