Antiques Roadshow

Seasons Greetings!

The Truth About Antiques Roadshow

First of all, few Americans know that the Public Broadcasting Corperation (PBS) basically pinched the format for the show from the British, who had their own Antiques Roadshow going long before the Americans started theirs; but my guess is that Britons prefer the American programme over their own original. The British show is too tepid and sedate for Americans. It also appears out of focus or "pre-exposed." Film-makers sometimes pre-expose film to wash out some of the color and give the images a somber or colorless tone.

A British Antiques Roadshow host appraises an Oriental bowl

The American Roadshow consists of average citizens in different cities bringing their paintings, jewellery, and other objects for the Roadshow hosts to appraise. Often the camera focuses on the faces of the average citizens, on the gleam of expectation in their eyes. A favorable appraisal of their objects may send them into a state of shameless rejoicing.

Although American viewers rate the Antiques Roadshow highly, PBS itself reacts ambivalently to the programme. If PBS needs to broadcast a special, they invariably pre-empt the time slot for the Roadshow. For one thing, the Roadshow indulges its guests and viewers in wishful thinking and materialism, when they should show more concern for social justice, tolerance and diversity, and the environment.

PBS has to face the fact that people don't want only social justice and tolerance. They want money and nice things. America may have an advanced infrastructure and humanitarian social programs; but people want stuff that is worth good money. If they have nice things, they want more! Getting a favorable appraisal makes them speak off-the-cuff. Afterward, they regret howling so openly over their good luck.

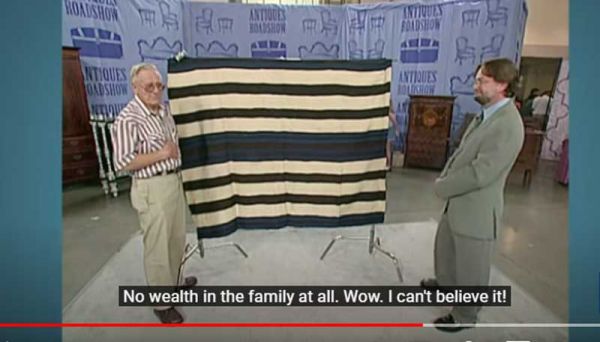

This happened in 2001 to an Arizona man named Ted Kuntz. Ted brought a Navajo blanket into the Antiques Roadshow in Tuscon. Appraiser Donald Ellis looked at it in disbelief and told Kuntz that it could sell for as much as a half-million dollars. Kuntz could hardly believe his ears. He had grown up with the blanket and never regarded it as anything special. He said, "It was just laying on the back of a chair!" His voice choked up, and he was near to weeping.

Ted Kuntz:

"Wow. I can't believe it. My grandmother, you know, were poor farmers. They didn't, uh—She

had, uh—Her foster father had started some gold mills and discovered gold and everything, but

there was no wealth. No wealth in the family at all. Wuh! I can't believe this. . . . Jeez, I had no

idea it could be worth anything like that. I thought maybe six or seven thousand dollars at the

most—it could be worth, which would have been a big something, at that time."

It's so interesting to listen to the guy cry. You'd think he had some idea of the cultural significance and history of the blanket. All he could think about was that it involved serious money, much more than he had ever had before.

In a capitalist system—that is to say one powered by freedom-loving concepts that enable a market, everything has a value. The free-market lets objects float up and down, but they retain a negotiable value. The man who bought the blanket from Kuntz donated it to a museum in Detroit. Let's face it. That's like putting it in prison or a cemetery. He took it out of circulation. Museums are end-stations for nice things because so few people ever go there—a cultural retirement home.

Nice things in museums belong to the government, now, and hang on the wall collecting dust. In a free society, everything belongs to someone. Scientific processes, literature, and other intellectual property, films, newspaper cartoons, and rap videos, as well as the traditional stuff like silver, gold, money, and real estate—they all belong to somebody.

Likewise, in a free society, the human elements all belong to somebody, even if the bonds that hold them differ. Employees, husbands, wives, and children belong to somebody. In a free society, that should be the norm. Children belong to you, me, or someone else. The idea that Americans need to take care of "America's children" smacks of fraud. In a free society, "America's children" are all in jail or some other government end-station.