Bernard Shaw's Major Barbara

Bernard Shaw's Major Barbara

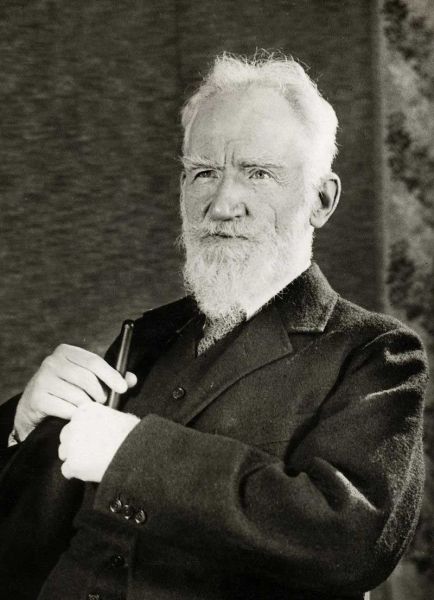

George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) shares the fate of most famous literary figures—that few people actually read them. In the case of Shaw, they may remember "The rain in Spain falls mainly in the plain" and "I could have danced all night," from the musical My Fair Lady, based on Shaw's play Pygmalion, and they may also remember the opera The Chocolate Soldier by Oscar Straus, based on Shaw's play Arms and the Man; but active knowledge of his work resides in no more than three percent of people in any country, Britain or the U.S.

Part of the modern disaffection towards older writers derives from the evolution of the language. People simply don't talk like the characters in Shaw's plays: they speak nineteenth-century English and talk about horse-drawn carriages and "cinderellas"—the poor women who clean the fireplaces and coal-stoves every morning. Shaw also loves to create characters who speak with working-class dialects, which modern people can't understand.

Shaw is also full of surprises, which readers don't like—a Marxist who champions the individual, a Socialist who champions Capitalists, or a Pacifist who champions a strong military. Shaw likes to engage in subtle criticism, rather than openly. It works against popularity amongst over-entertained, modern people who read on the run. His characters represent the commonplace, pedestrian society where everyone wants to get ahead, with subtle insights embedded in the dialogue.

Shaw simply doesn't fit the norm. The political Left would like everyone to believe that Capitalism effectively limits great accomplishments to the upper-class of privileged, connected people; so they have difficulty explaining how George Bernard Shaw, the son of an alcoholic who left school when he turned fourteen, could have accomplished so much. He is, after all, one of three most-important playwrights in Western literature.

He apparently read voraciously. How else could he have written Caesar and Cleopatra, Androcles and the Lion, or Saint Joan? Shaw also liked to create characters who rise in London Society by pretence. Mrs. Warren's Profession, for instance, tells the story of a London woman who emerges from poverty to become a celebrity "Madam". The social-cost of her rise to prominence requires a day of reckoning from her well-to-do children—how they should live.

For this post, I will talk about another Shaw play, Major Barbara. Barbara Undershaft, a major in the Salvation Army, lives with her mother, Lady Britomart, in London. After many years, Barbara and the rest of her family reunite with their estranged father, the armaments-manufacturer Andrew Undershaft. Their names remind me of Charles Dickens's characters.

Barbara informs everyone that unless she can get more money, her little Salvation Army mission in the West Ham section of London will close. Her father offers to buy the mission to save it, but she refuses, believing that his manufacturing of weapons taints his money. Undershaft shares some of Barbara's humane intentions, but has a different approach. He would rather put people to work than give them hand-outs. His dialogue with Barbara's fiance Adolphus Cusins expresses his vision of the ideal society:

Cusins: Excuse me: is there any place in your religion for honor, justice, truth, love, mercy, and so forth?

Undershaft: Yes: they are the graces and luxuries of a rich, strong, and safe life.

Cusins: Suppose one is forced to choose between them and money or gunpowder?

Undershaft: Choose money and gunpowder; for without enough of both, you cannot afford the others.

Contentious argument defines Major Barbara—sometimes bitterly contentious arguments—over the inequalities in a freedom-loving society, people sitting in the cold thwarted by poverty, and the idea of a society driven by profit, even profits derived from armaments manufacturing. Major Barbara seems to invite audience participation.