CHAЯLY

Do you know about the Paris Commune? B. F. Skinner? The Children's Crusade, or Nietzsche? If you hang out with intellectuals in high school, they may expect you to know. You should expect these tests to go on from people who want to know if you are really "one of us." I hung out with intellectuals and had to anticipate the interests of the other guys and inform myself, so that I would know a thing or two about them when they asked me.

My reader should remember—if he does not already know it—that membership in a human group worth its salt involves testing its members for their level of loyalty or engagement. Everyone wants to know, "Are you with us?"

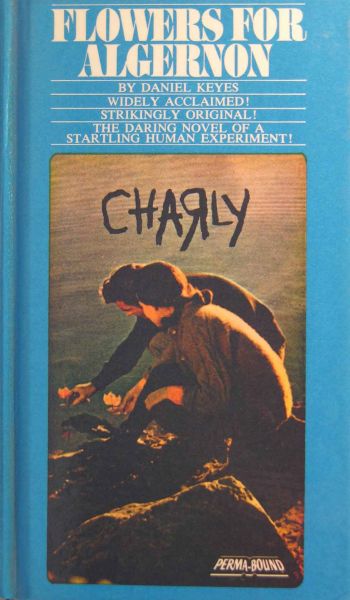

I don't remember when Flowers for Algernon came into my life. Someone else may have discovered it and passed it on to the rest of us. There is a kind of showmanship in "discovering" books. You try to look like you've been lying on the floor for some hours and can only slowly gather yourself up from the blessedness of encountering a really incredible piece of writing. As you dust yourself off, your clothes sparkle, as if you have actually lain on a bed of stars. The ritual of learning gains a touch of magic that way, which the classroom could never impart. Knowledge gains a human dimension, apart from the foie-gras farmhouse where it lives most of the time.

Discovering a book or a writer before anyone else gave me a competitive edge over the others in the group. Just high school boys, we always tried to prove ourselves as worthy of inclusion in the "Intellectual" clique. That striving kept the vitality of our group in shape.

Flowers for Algernon touches intellectuals in a number of ways, since it deals with an intellectually handicapped man Charly Gordon, a ward of the state, who undergoes experimental surgery and grows into a genius. With his improved brainpower, Charly can challenge even the researchers and surgeons who helped him, and challenge them he does! He remembers how they laughed at him before he had the surgery.

Tension and competition characterize even the relationships among the scientists and their supervisors—bitching and backbiting between the haves and have-nots among the highly-educated—lots of egos riding on Charly's performance. He bristles a little at his guinea-pig status.

Charly has to deal with an irreconcilable dual life, and he knows that his old life will have to give way to a new one. He would rather stick with his old life, even if he lives as a retarded man with a menial job in a bakery. It gives him the security of a social group among likewise mentally-challenged men. The circumstances of his life change when his boss asks him to mix the flour to make bread. Charly's predecessor needed two-years training to do this. Charly mixes the flour with no training.

It stuns the other employees. He even mixes the flour better than his predecessor did; but soon their feeling about Charly changes. His superior intelligence convinces them that they don't want Charly around any longer. He is no longer one of them. They tell their union reps, and Charly's boss reluctantly fires him to keep the peace among his workers. This loss of identity among people he had considered his friends hurts Charly deeply. The insight about human-kind, that he craves a group of others like himself, impressed me.

Charly has all this new intelligence, but he does not feel entirely comfortable among the scientists who have given him a new life, and he starts to goad them resentfully. Like any high school intellectual, he wants to find his place in this new environment. He is not just their guinea pig but their equal—one of them.

Charly hates the supervisors Nemur and Strauss for their arrogance, their bossiness, and tendency to put down their subordinates—even though they pioneered the very surgical techniques that revitalized Charly! He realizes they only did it for the glory of another professional achievement. They care little for him as a person. Charly is only an asset, like the laboratory mice.

Perceptive high school intellectuals will realize a few things about Charly that apply to them, too. Although Charly becomes a genius in middle-age, he remains a child at heart—an innocent. He cannot see the motives or character of high-achieving adults except in a negative light. In terms of personal orientation, he can only see adulthood as foreign territory—like Holden Caulfield! And of course, all of us intellectuals had read The Catcher in the Rye and remembered Holden haranguing Sally Hayes about "phony" grown-ups.

Charly interrogates his medical supervisors vindictively: how much do they know about anything?

I found out.

Physics: nothing beyond the quantum theory of fields.

Geology: nothing about geomorphology or stratigraphy. . . .

Little in mathematics beyong the elementary level of calculus of variations. . . .

I slipped away to walk and think this out. Frauds—both of them.

One of the junior scientists listens to Charly run down his supervisors, and he tries to help Charly understand the plight of professionals. The angry vitality of the dialogue in this book left an indelible impression on us high school intellectuals—still under the influence of Holden Caulfield:

"Take it easy, Charlie. The old man is on edge. This convention means a lot to him.

His reputation is at stake."

"I didn't know you were so close to him," I taunted, recalling all the times Burt had

complained about the professor's narrowness and pushing.

"I'm not close to him," Burt looked at me defiantly. "But he's put his whole life into

this. He's no Freud or Jung or Pavlov, or Watson, but he's doing something important,

and I respect his dedication. . . ."

"I'd like to hear you call him ordinary to his face."

"It doesn't matter what he thinks of himself. Sure, he's egotistic, so what? It takes

that kind of ego to make a man attempt a thing like this."

Becoming an intellectual made learning a personal matter, something extracurricular. Not only did knowledge matter to me. It also mattered to the other guys in our clique, who wanted me to hold up my end of the learning process.

Likewise, reading Flowers for Algernon turned my growing up into a personal thing. I think it had that effect on all of us. Charly acted as a proxy by confronting our own angst about the process. He gave adulthood a face in transition. That was an experience we could follow. We had enough of an inkling about that adult face to see what was in store for us.