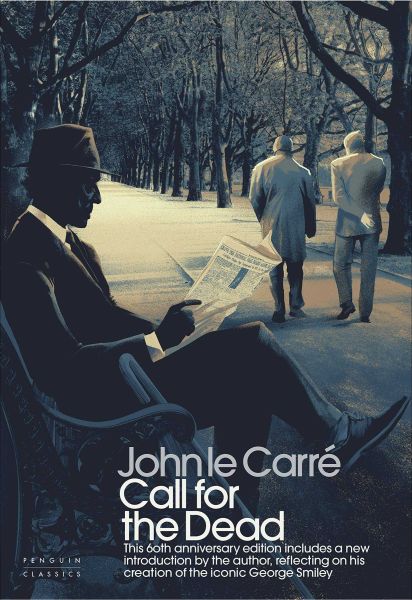

Call for the Dead

Call for the Dead, by John leCarré

I remember watching a British film, whose title I did not bother to learn, during the late 1960s, in my parents' home in Columbus, Georgia. Mostly, I remember the last scene where two old friends, who have become reluctant enemies during the Cold War, get in a fistfight on a pier beside the Thames River in London. One man falls off the pier, and the river-current pushes an old barge over him, crushing him brutally against the pier.

Somehow, I stored the film away in my brain. Then, twenty-odd years later, the BBC filmed a mini-series production of John leCarré's novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, starring Alec Guiness. I liked it so much, I resolved to read every novel that leCarré had written.

His first novel Call for the Dead came out in 1961. As I read it, I had a sensation of déjà vu. At the end, two middle-aged men fight on a pier beside the River Thames. One man pushes the other into the river, where an old barge crushes him. So I did some research on Call for the Dead at the local library (pre-Internet) and learned that the film-director Sidney Lumet had filmed it with a different title, The Deadly Affair, starring James Mason, Simone Signoret, and Maximilian Schell. Lumet also changed the name of the main character from George Smiley to Charles Dobbs.

The plot concerns a foreign-service officer Samuel Fennan, in London, who commits suicide after the British government's counter-espionage agency learns about his past relationship and current sympathy for Britain's Communist Party. A counter-espionage officer, George Smiley, who handles the case, has to visit Fennan's widow Elsa, "and so far as good feeling allows, question her on all this."

The "good feeling" does not go very far in Smiley's meeting with Mrs. Fennan, who hides her anger behind weary defeatism.

She browbeats him for his interrogation of her husband—"about loyalty!" she adds with a restrained, incredulous lilt, laden with grieving exasperation: her husband, a loyal British citizen, a Jew, and refugee from Nazi tyranny:

"It was a game," she said suddenly, "a silly balancing trick . . . it had nothing to do with him or any real

person. . . . Go back to Whitehall and look for more spies on your drawing boards. . . . It's an old illness

you suffer from, Mr. Smiley . . . and I have seen many victims of it. The mind becomes separated from

the body; it thinks without reality, rules a paper kingdom, and devises without emotion the ruin of its

paper victims."

Stung and hurt, Smiley counters, "Look, Mrs. Fennan, that interview was almost a formality. I think your husband enjoyed it. I think it made him glad to get it over."

"How can you say that?" she asks him bitterly. "How can you? Now, this. . . ."

The ringing telephone interrupts her. Smiley answers the phone himself and hears a woman's voice tell him it is the wake-up phone-call he requested. But Smiley did not request a phone-call, and he knows Mrs. Fennan did not order it, either. She has already told him she is an insomniac and sleeps little; so Smiley suspects already that her dead husband ordered it—hence the novel's title.

Later, Smiley receives a letter at his office from the dead husband that asks for a second interview. Smiley concludes that he was murdered to prevent the second meeting. He subsequently puts Mrs. Fennan under surveillance. His team follows her to a meeting with her East German spy-controller, Dieter Frey. Based on what he sees, Smiley realizes that Frey is her lover, as well, and that he used Mrs. Fennan to spy on her husband and to read the classified papers that he brought home from his office.

What an extraordinary deception Mrs. Fennan has perpetrated! But Smiley works in an agency that tracks down spies, for whom stealth and deception come with the turf; and he takes her actions in stride. Mrs. Fennan has theatrical ability that may earn her star-billing, once she gets out of prison. As I closed the book, I wished I could have asked, how much of her display of defeatism and grief was genuine?

I wish Smiley could surveil a few browbeaters in our current American society, and find out who their real lovers are—not the social justice and diversity they claim—who enable them to rail about right-wing witch-hunts, racism, sexism, and homophobia. I feel the same wonder Smiley must have felt—how these people live with themselves, poisoning the society with their performances? For the rest of us, the constant browbeating has left us cynical and dismissive, which is too bad.