Competing Ideas

Gerard Baker, former editor-in-chief of the Wall Street Journal wrote an opinion piece on the same page as Senator Sasse's article. Gerard starts his article by stressing intentionality and positiveness. The start of the New Year, Bakcer writes, should give us "optimism, that timely annual infusion of resolve." But Gerard has passed the age of sixty now, "and the iron of realism has take up residence in the soul."

In the third column, near the middle of the page, Baker states his appropriately central thesis, "Can we strive to keep two competing ideas in our heads at the same time?" His wording is unfortunate. If we come to a fork in the road, if we absolutely have to choose one path or the other, how will we decide if the "competing ideas" involve one path or the other—and we can't straddle them.

We will need more than a debate of the advantages and disadvantages of each. We need orientation and a manual to guide our actions, because we may have to decide quickly—like, yesterday. If you fly a plane and encounter a problem, you consult a manual for directions. You may have to make a decision quickly; so you have to access solutions easily. Competing ideas won't work in a situation that requires a quick response. That is why we have a constitution, our policy manual. The debating preceded its ratification.

Our U.S. Constitution has worked pretty well. People on the Left criticize America's "constitutional originalism," but if leftists do not like the Constitution, as written, why change it? Why not create a constitution of their own? Any debate you have about the content will have to precede ratification. A constitution gives a government a wholistic approach, delineates responsibilities and powers, and organizes its functions. With a constitution in hand, the Left can break off from the Right and create its own nation, that embodies its values as a given.

If my reader can continue reading down the middle column, you will come to a central question of Baker's article: "Can we start to work to eradicate the binary mind-set that has seized our thinking?" He means, can we stop thinking about a solitary right way and lots of wrong ways? And recognize that any of a number of solutions will suffice?

He continues, "It's ironic that Americans, who have created the most dynamic and brilliant country in history have become so seized of this binaryism." Again, America did not get its dynamism and brilliance by considering the alternatives. It succeeded with constitutional orientation and structure.

We simply haven't the time to consider lots of options. Everyone wants action yesterday.

Baker insists that "This isn't a call for some kind of intellectual relativism. . . . It is a call for a hint of skepticism in the face of absolutism."

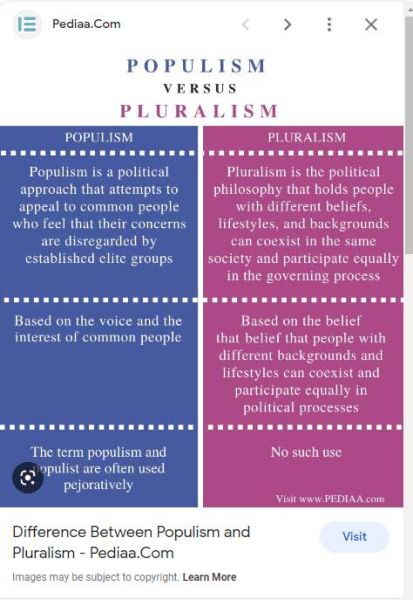

But if he wants to talk about absolutism and binary-thinking, he really should direct his attention to leftist writing in places like Facebook. Just look at Pediaa.Com's simplistic definitions of pluralism and populism. The Right also cannot match the Left's arbitrariness to force the issue.

Baker concludes the article with "Our domestic political and cultural differences are significant and enduring. But are they really an existential challenge to our way of life?" In the end, he equivocates: "I'd say not. But I could be wrong." I'd say you need the answers before the questions begin.

I suspect Baker, like most successful conservatives, lives in a peaceful, leafy suburb, far away from the tumult in society. In public schools, churches, organizations, and city squares, the heated debate goes on, excacerbating the divisions. The divisions will only end, in fact, when we divide—like the Czech Republic and Slovakia—peacefully—or like British India and Yugoslavia—in conflicts that result in the deaths of thousands.