Do You Know the AfD?

Do You Know the AfD?

This photo of German politician Bernd Lucke makes an unfortunate impression on a viewer, inasmuch as he waits in the background, looking like a golf-ball that lands in the rough, while the white poodle prances past in the foreground. The photo reminds me of Bernd Lucke's political career. He was an economics professor who helped to found the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) political party—a protest party that split right-wing voters in Germany the same way Donald Trump split the Republican Party in the U.S. After infighting, Lucke lost his hold on the directional agenda of the AfD. He resigned to start his own political party, the Liberaler-Konservative Reformer, and almost disappeared from the political scene.

"Kennen Sie die AfD?" the title asks. (Do you understand the AfD?) It appeared in the July 19, 2015, Frankfurter Allgemeine-Sonntag newspaper. The title resonates with Germany-watchers who have to admit they do not understand the AfD. Its leadership has changed often and acrimoniously, that many wonder if it can survive. How much have the changes altered its talking-points and policy-initiatives? How much have the leaders' controversial remarks discredited the Party?

Lucke wanted Germany to pursue market-oriented economic policies to safeguard its stability and high standard-of-living. Pressured by the AfD's other leaders, Lucke had to step aside in favor of his deputy, Frauke Petry, who wanted to concentrate on other issues, like third-world emigration to Germany, the rise of Islam, and the threat to the nation's historical Christian culture.

Other points argued by the AfD include Germany's membership in EU, the European Community, and its use of the Euro currency. The idea of a single currency in Europe worked for the same reason that the Dollar works so well as the only currency in this country, namely that it facilitates trade. Europeans can visit any member-country of the EU and use the same currency.

I can still remember the old days, when a tourist had to change money at the border—Spanish Pesetas to French Francs, Francs to Italian Lira, and finally Lira to Austrian Schillings. Money-changing stations at the border-crossings made a killing off poor tourists.

If only the member-nations had behaved responsibly, the Euro would have made a killing, too, reproducing itself as well as the Dollar, but some of the EU nations did not behave responsibly, and German voters hated having to bail them out—nations like Spain, Greece, and Italy, that did not live within their means. The EU threatened to remove them from the Euro-zone, but to little effect.

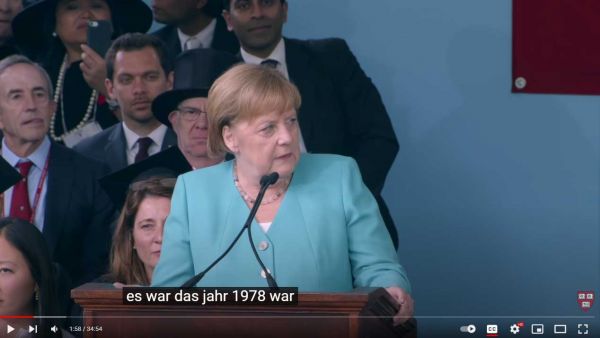

But few of the critics of the AfD mention the main reason why the Party succeeded so well—former Chancellor Angela Merkel's neglect of the provinces of East Germany. The Germans in Saxony, Brandenburg, and Thüringen—the AfD's core supporters—hated Merkel's turning her attention to the refugees, neglecting the problems of East Germans.

Merkel's credibility has one other problem in the East. She has no children, therefore no investment in the future, no hostages to fortune, no continuing connection to life in the present—unlike Bernd Lucke who has five children. Lucke's successor at the AfD Frauke Petry has six. The first AfD party chairman Jörg Meuthen also has five; but once Merkel departs this life, her connection to it ends.

The heavy toll in leadership personnel and idealism that the breakaway AfD Party has experienced should serve notice about the risks of stepping out of the mainstream of politics. Whatever the Republican and Democratic Parties do not have, they do have accrued endurance and some philosophical stability—or wiggle-room—which tends to elude breakaway parties.