Dr, Antje Bauer

Dr. Antje Bauer, director of the Stadtarchiv (City Archive) in Erfurt, Germany, looks over the pile of projects that she oversees. The challenge of sorting them out does not seem to faze her. As director, she wears many hats—event-organizer, publicist, publisher, cultural custodian, historian, librarian, lecturer, and of course as a writer. My reader can detect the variety of challenges in the desk-clutter. In the next photo, she delivers a lecture in a reception room at the Erfurter Rathaus, the City Hall. Iit's a remarkable building.

One day, she took me on a tour of the Stadtarchiv. On one floor, the Archive stores issues of every newspaper ever published in Erfurt. On another, it keeps records of all kinds of transactions going back to the 13th and 14th centuries. Each day, someone has to check the air-conditioning to keep the humidity at the desired level, in order to preserve the old documents.

In addition to all that, each departing administration of the local government turns overs its records to the Archive, which stores the records for historians. In addition, when important people in Erfurt pass on, they bequeath their personal correspondence to the Archive. Great-great-great-grandfather Johann Blasius Siegling was close friends with Field Marshall Neidhardt von Gneisenau, a military leader from the early 19th century. The Archive actually published some of their letters.

Institutions like the Stadtarchiv occupy a high position in German culture, much higher than in this country. For all the depredations of the Nazi and Soviet-eras, the Archive has retained a remarkable level of completeness. Like any museum or art gallery, it has to negotiate occasionally with private citizens for the purchase of old documents.

I first met Dr. Bauer in 2010 when I was writing a book about my Siegling ancestors. Great-great-grather John Siegling emigrated to Charleston, South Carolina, in about 1818. We Bowers children had heard all our lives how our immigrant-ancestor braved the odds and journeyed to America to seek his fortune.

Then, in about 1993, my mother found a collection of letters from great-great-grandfather's lifetime and asked me to translate them. I was still working at the time and did not have much time to spend on them; but the letters interested me enough, so that I squeezed in the time—more and more time as my interest grew.

The Siegling letters mentioned names and places I had never heard of, so when I started to write my memoir of the Sieglings—published in 2014 with the title Freedom is a Public Utility—I went to the Stadtarchiv and asked for help.

Antje was in her office and agreed to help me. I told her about a letter from 1812 that Great-great-great-grandfather Blasius wrote to John in Paris, while Napoleon's army occupied Erfurt. Antje said that two scholars of the Archive, Rudolf Benl and Walter Blaha, had co-authored a book on Napoleon's occupation of Erfurt, titled Erfurt als Domäne Napoleons in 2008, to commemorate the experience two hundred years after the fact.

Antje said that Blasius and some other citizens had registered their tiny protest to the high taxes the French levied on them. The French sternly warned Blasius not to complain again. They even read his outgoing mail. When I learned this, I re-read Blasius's 1812 letter to John and realized Blasius must have known it, too.

John Siegling's sister Ottilie wrote him several times during the turbulent years of the Revolution of 1848. When I asked Antje about it, she said the Archiv had published a book about the Revolution in 1999, titled Königstreue und Revolution. She contributed to it, along with Benl, Blaha, and other scholars at the Archiv.

In around 2005. a musician friend of my mother's told me about concerts he had played in Erfurt in the 1970s. He complained that the night-time air in Erfurt during the Winter was so toxic, he could not go outside. I mentioned his story to Antje, who explained that Erfurters typically burned high-sulphur brown coal to heat their homes during the Soviet East-German era. The burning produced acidic, sulphur-dioxide smog that hurt a lot of people. Antje directed me to the Archive's monthly Stadt und Geschichte magazine that published a study in 2005 on Erfurt's air-pollution during the Soviet-era.

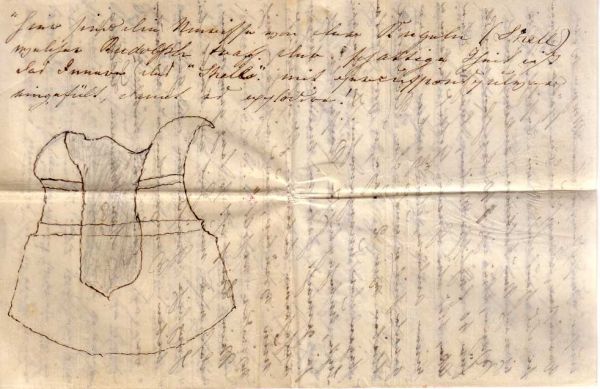

And so, over time, Antje became my go-to person, if I had questions about my Siegling ancestors. During one visit to Erfurt, I showed her the photo of a piece of shrapnel that had injured my Great-grandfather Rudolph Siegling during America's Civil War. She said the Archive had something that might interest me. It was a letter from Rudolph's father John to his sister Ottilie in Erfurt. Ottilie must have bequeathed the letter to the Archive at the time of her death. In the letter, John even sketched the piece of shrapnel. I could hardly believe my eyes!

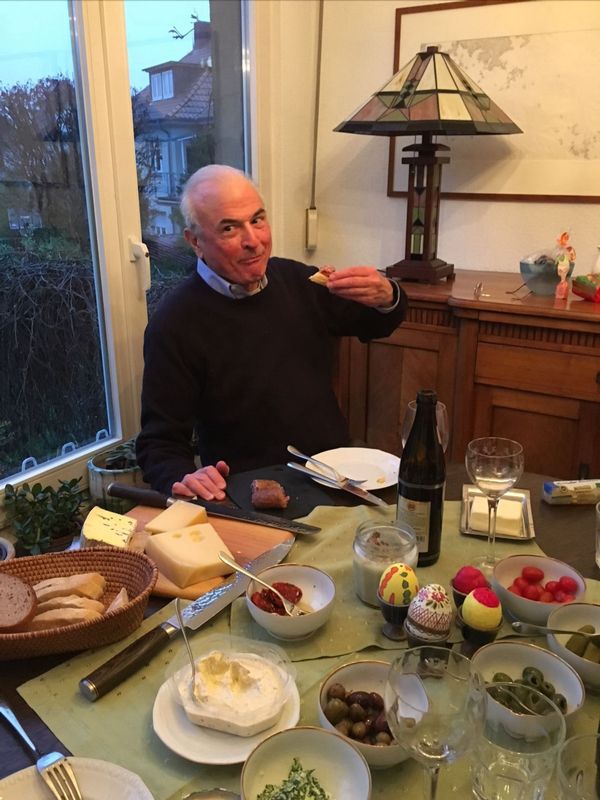

As time went on, I became friends of the Bauers and visit them each time I stay in Erfurt. You can see my child-like delight, sitting beside Dr. Bauer—confronted with so much good food and drink.

Her husband Jens, a physician in Erfurt, sits beside her in the second photo.

During another visit, they snapped a photo of me eating the best Wurst I have ever tasted—from a small village in Thüringen named Aschara--but hot and spicy!

During my August visit to Erfurt, the Bauers took me to Wartburg Castle near Eisenach, 40 miles from Erfurt. The Wartburg has an important role in the history of Germany. It was the residence of Frederick the Wise, Duke of Saxony, an early supporter of Martin Luther. With Pope Leo X and the Catholic nobility threatening to abduct Luther and take him to Rome for trial, Frederick carried him off to the Wartburg to keep him safe. During his stay in the Wartburg, Luther translated the Old Testament from Hebrew and the New Testament from Koine Greek. You can even see the tiny, spartan room where Luther worked, Such a humble settting for such a momentous event.

And so the Wartburg has particular significance for Lutherans. Luther didn't just translate the Bible. He gave the German language a kind of linguistic template.

Antje and Jens downloading the Wartburg's on-line tour.

To get from the car-park to the Wartburg, we must have climbed a thousand feet. The view from the wall was fantastic. We could see across the valley for miles. That explained to a large degree why this particular castle is still here, not like the hundreds of ruins that one can find in almost every part of Germany. It is a big place, and Frederick the Wise must have fixed up nicely in his day; so that it presented a big problem for potential invaders.

For the residents of the Wartburg, however, the need to maintain a staff and delivery of provisions must have presented some problems. There is only room at the top for a small garden and a small pen for livestock. Donkeys had to bring in supplies from the outside.

Antje told me that, as a child, she rode up to the Wartburg on the back of a donkey. During the days when everything moved by donkey, the donkey-trains bringing supplies to the Wartburg must have kept the staff busy 24/7.