Entrepreneurism in Nineteenth-Century Germany

Entrepreneurism in 19th century Germany

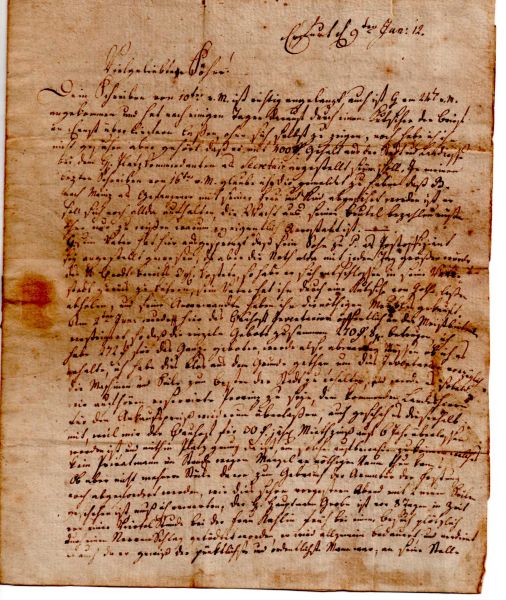

In 1993, my mother told me that she had found a collection of letters in my grandmother's personal effects, perhaps five years after her death. Mother had studied German in school and knew that the letters were written in German. Since I speak German, she asked me to translate them. With the help of German-speaking friends, I did this.

In 1993, I had already decided to wind up my unsatisfying working-life and to start something else. The letters did give me a new start, although in a direction I never expected. I started a new career as a writer, and I knew that I wanted, at some point, to contrast socialism and capitalism for modern Americans, and in a larger sense I wanted to demonstrate the differences between a free-society and an un-free one.

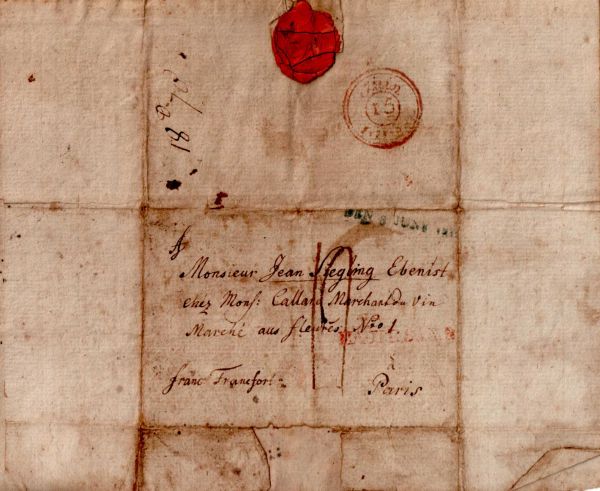

My great-great grandfather John Siegling grew up in Erfurt, Germany. John's father Johann Blasius Siegling wrote him regularly after he left Erfurt. The earliest letter, written in 1812, reached John in Paris; the next, written in 1815 reached John in Amsterdam. Sometime after 1820, he finally settled in Charleston, South Carolina, as the subsequent letters show—until Johann's death in 1835.

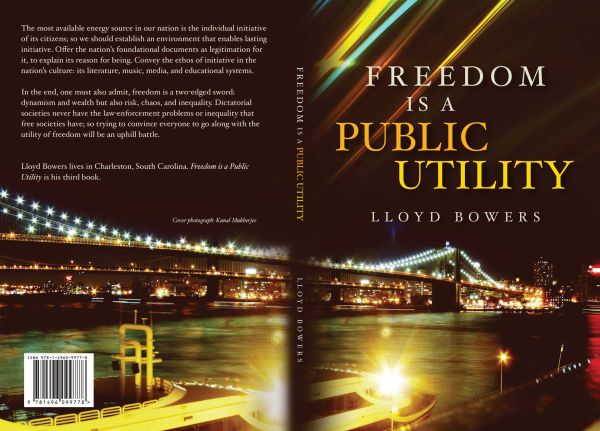

In his letters to John, Johann records the transition of Erfurt from rule by the Archbishop of Mainz to its inclusion in the Prussian Empire. I say "transition" somewhat euphemistically, because the event occured as a sort of take-over. The consequences of the take-over and their impact on life in Erfurt interested me so much, I published a book about it, titled Freedom is a Public Utility, in 2014.

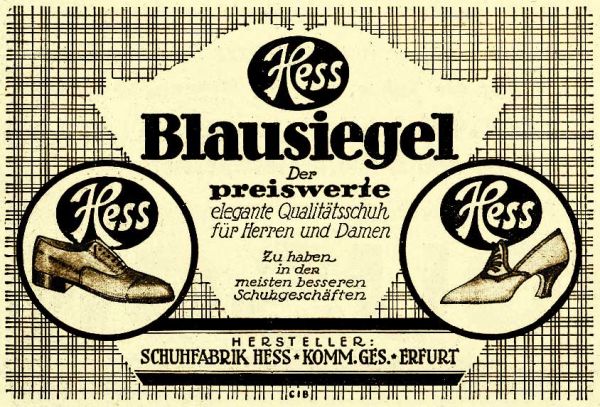

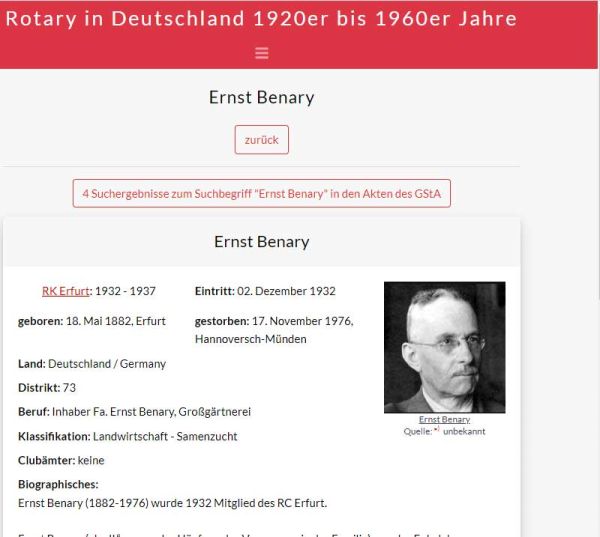

Among other things, Prussia offered citizenship to Jews. It also introduced free-enterprise, meaning that just anyone could start a business. He only had to pay for a license. Venture-capitalists offered capitalization to entrepreneurs—more or less as capitalism works today. These things happened just in time to enable the Industrial Revolution to unfold. Many people became rich as a result, some of them Jews. In Erfurt, the Hess Shoe Manufactory and the Benary Nursery are two examples.

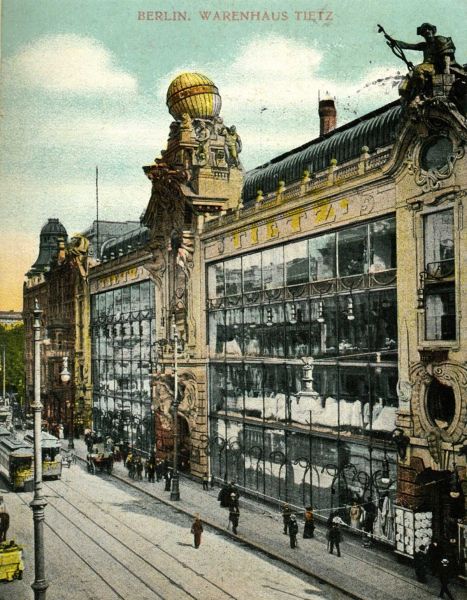

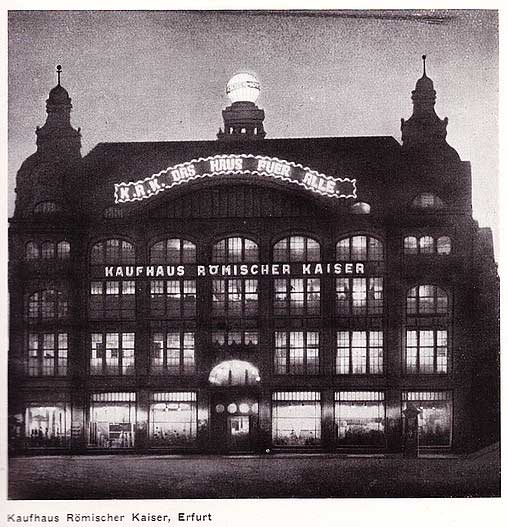

Ernst Benary sold plant-cultivars to landscapers and home-owners; Maier and Louis Hess started a shoe-manufactory; a family named Tietz opened a chain of department stores. The Tietzes wanted their customers to stay a long time, so they designed the interior as a rich, exotic atrium with skylights; they provided restaurants, spaces for small children, and they were a rip-roaring success. Among other stores, they owned the WarenhausTietz chain and the Kaufhaus Römischer Kaiser in Erfurt. Not only were the Tietzes Jews, they were also free-masons and declared their allegiance to free-masonry with a masonic-globe on the roof, that lit up at night.

The wealthy in Erfurt wanted their own place to relax, socialize, and dine; so they created a private club called Die Erfurter Ressource. As the name suggests, they did not merely enjoy their free-time at the club, the club also gave them a private space where they could restore themselves and interact with others like themselves, either to share opinions or to talk business. People of that time rated the Jewish entrepreneurs as part of the Establishment, and a lot of people hated them, more or less like modern times. The political markers aside, a portion of every modern society hates the "Establishment."

Not surprisingly, all this led to some push-back. In Erfurt, for instance, Walter Corsep published his cartoons against Jews and Capitalism. Historians describe him as an anti-capitalist and anti-semitic conservative. For a modern American, this was too much: conservatives against Capitalism? But in the nineteenth century, "Conservative" meant loyalty to the monarchy, the Church, and the military. Curiously, these same people denoted entrepreneurs as "liberal."

The entrepreneurs, after all, had started the "Industrial Revolution," the most revolutionary action since the Reformation. The Revolution caused many German craftsmen to lose their livelihoods. Shoemakers lost out to shoe manufactories. Window-builders and brick-masons lost out to factory-made products. My Great-great-great-grandfather Johann Blasius Siegling, for one, hated that the Industrial Revolution caused the decline of so many self-employed artisans. Modern Americans need to see our current nation in the same light. It's like a birthing.