Eric Hoffer and the Dynamics of Hatred

In True Believer, Eric Hoffer studies the components of a mass-movement, in order to explain its origins, instigators, and intentions, and its role in rebellions and revolutions. True Believer deserves renewed attention in contemporary America, in light of the renewed risk of revolution shaking the earth under our feet, as we speak.

In chapter 14 of True Believer, Hoffer deals with "Unifying Agents", the forces necessary to get a mass-movement started. In the first section of chapter 14, Hoffer takes up the subject of "Hatred" as a unifier.

From Axiom 65:

Hatred is the most accessible and comprehensive of all unifying agents. . . .

Mass movements can rise and spread without belief in a god, but never without belief in a

devil. . . .

Hoffer also quotes an early Nazi-defector who said that, if the Jew-enemy did not already exist, the Nazis would have to invent him. Hoffer says similar things about the Soviet Union who, right after the end of World War II, turned their propaganda-machine against the U.S.

Continuing with Axiom 65, Hoffer writes,

It is doubtful whether any gesture of good will or any concession from our side will reduce

the volume and venom of vilification against us emanating from the Kremlin.

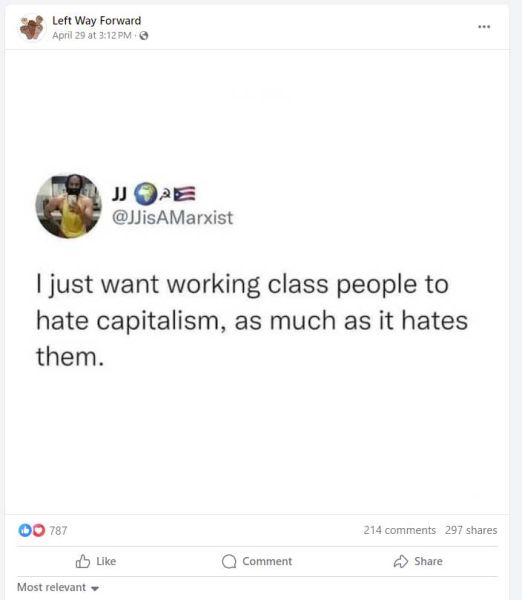

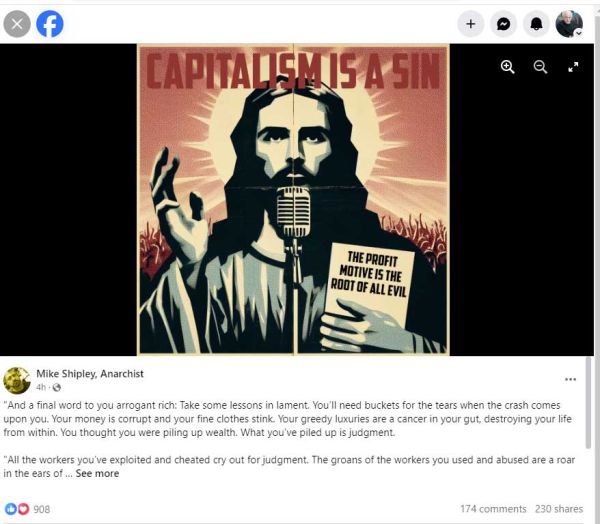

This kind of implacable hatred reminds me of left-wing bloggers that I see on Facebook. As with the Soviet Union, I doubt that "gestures of good-will" or "concessions from our side" will mean a thing to the bloggers. Hatred has awarded them a precious energy, too important to allow others to water it down.

I keep querying the bloggers, "How will you replace Capitalism? How will you redesign society, after you have destroyed it?" Hoffer explains that the nihilists do not think that far. In Axiom 74, he writes the following:

They see in a general downfall an approach to the brotherhood of all. Chaos, like the grave,

is a haven of equality. Their burning convictrion that there must be a new life and a new

order. . . . The old will have to be razed to the ground before the new can be built. Their

clamor for a millennium is shot through with a hatred for all that exists, and a craving for

the end of the world.

Hoffer continues his line of thought into Axiom 68:

When our hatred does not spring from a visible grievance and does not seem justified, the

desire for allies becomes more pressing.

Hoffer then tells the reader about the origin of "unreasonable hatreds"; they grow out of a loss of faith in oneself. If you no longer believe in yourself, and you tear yourself down, day after day, the accumulated rage has to go somewhere. Ending Axiom 68, Hoffer writes,

Self-contempt produces in man the most unjust and criminal passions imaginable, for he

conceives a mortal hatred against the truth that blames him and convinces him of his faults.

He continues this thought into Axiom 73:

It is easier to hate an enemy with much good in him that one who is all bad.

A mass movement may feel contempt or condescension toward its inferiors, but those feelings do not fuel the unifying hatred that a mass movement needs. Likewise, it lacks the outrage to condemn thieves and murderers. It would rather condemn the leadership of the government and its powerful institutions. It saves its hatred for those above them, or better than them—such as Americans. Hoffer writes about Americans,

Americans are poor haters in international affairs because of their innate feeling of superiority

over all foreigners. An American's hatred for a fellow American . . . is far more virulent than

any antipathy he can work up against foreigners.

Finally, in Axiom 77, Hoffer issues this warning:

When we renounce the self and become part of a compact whole, we get rid of personal

responsibility. There is no telling to what extremes of cruelty and ruthlessness a man will

go when he is freed from the fears, hesitations, and doubt . . . that go with individual

judgment.