Founding Father Credo: Alexander Hamilton

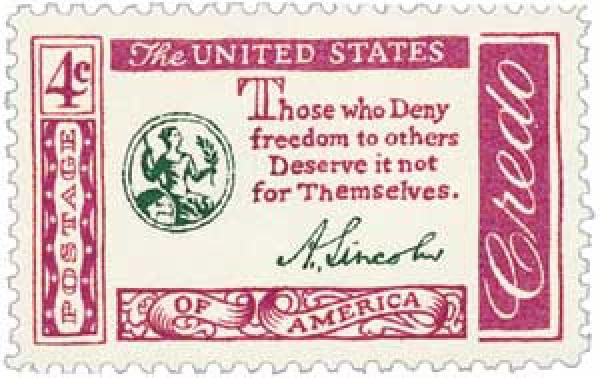

Abraham Lincoln more or less lucked into the Presidency—or unlucked into it, depending on how you view his career. His rugged looks and rural, ax-wielding background lent more to his reputation than it should have. The duration and level of destruction caused by the Civil War suggests that he lacked the education, diplomacy, and basic social skills to enable him to coax the opposing forces to a stand down instead of going to war. Lincoln was too much a creature of his political party, in debt to the power-brokers, and it limited his own exercise of leadership.

In short, the Civil War should never have happened. We always say that about war and wonder why it keeps happening. A lot of ingredients create circumstances ripe for war. The ingredients include a succession of slights—many, many, miniscule slights, the brusk handling of sensitive issues, and a more or less macho-approach to problem-solving at every level—more or less like the stand-off that afflicts America, today.

Madison, Washington, and Hamilton could have finessed the situation better, I believe. Historians must secretly know this, and regret that newly-elected President Lincoln did not get a better grasp of the significance of the events to guide his negotiations with the warring parties over the volatile, regional issues.

The Confederacy basically blundered into the Civil War—starting in Charleston, South Carolina—when it bombarded an off-shore U.S. military installation. This incongruous action set into motion the mechanics of war. Confederate apologists have a difficult time explaining the rationale for it. Bombarding Fort Sumter brought war to America's door-step, long before Americans had digested the consequences of the "opposing-sides" thing—a state of war between the people of the nation.

The call to war was really Lincoln's call. He had an obligation to step away from the party-bosses who had given him his career. Egged on by patriotism and the women in their lives, the young men of that era marched blindly into battle, many thousands of them dying in suicidal charges—mowed down by musket-fusillades and cannon-fire. Such a pity!

The Confederacy really lost the War before it even started, given the disparity in economic might. The Northern industrialization and immigration gave it a much better standing, against the Southern tiered, agrarian society. Lincoln should have taken the gentleman's approach and invited the Southern leaders to a state-dinner and explained the problems they would have faced in a war with the North. He could have profiled Southern leaders ahead of time to learn more about their motives.

A psychologist-profiler can pick on the defensiveness over the loss of faith in a value-system, that reveals itself in incompetent, blustering diplomacy. But such things happen often when disunited people brood and obsess on each others' evil intentions, more or less like the situation America faces today. Gripped by the paranoia of unseen enemies, clueless people lash out blindly against each other.

The pity is that the Confederate States had already achieved the most important step in resolving the disunity in slavery-era America. They seceded from the Union. They pulled it off, established their own government, elected officials, and built an independent life. Interestingly, the government of the Confederate States basically replicated the Federal Government of the United States, but on an independent footing. Regardless of what a reader thinks of the Secession of the Confederate States, they showed that a division is doable. That Confederate bar-hoppers lost their heads and started the War does not discredit the creation of a new nation.

Lincoln's reputation rests on a number of poorly-defined presumptions about the achievements of his Presidency. The presumptions contribute to a kind of cosy view of him, which no one has had the heart to challenge, in view of his assassination by a conspiracy of Confederate sympathizers.

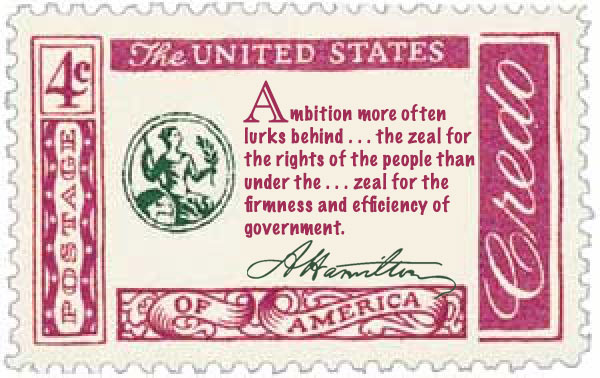

Alexander Hamilton Credo Stamp

For that reason, I decided to exclude Lincoln from the Credo stamp series, along with Benjamin Franklin, Francis Scott Key, and Patrick Henry. I would not mind including them in a series of ten or more Credo stamps, but Lincoln—his quote and nearly everything else about him—suggest a man who lacked the decisive, insight-driven leadership of a forward-thinkng statesman.

Simply put, Lincoln was not a Founder, not a visionary. The Founders performed exactly as their name implies: they founded a nation—a truly great nation! And we can have it again, if we play our cards right. I don't think Lincoln could have held his own with the Founders. I don't think he would have carried much weight during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, enough to secure his invitation to it.

Like John Adams and James madison, Hamilton read voraciously. He studied the history of nations and philosophy, in order to determine what kind of nation worked best. Like Adams, he developed a negative view of Democracy. He liked a Republic, a "nation of laws, not of men."

Based on his research, Hamilton predicted that America would evolve from a constitutional republic into a partisan no-man's land. This perceptiveness about the tendency of democracies deepens my respect for Hamilton, even while it scares me. He wrote in the Federalist Papers:

To judge from the conduct of the opposite parties, we shall be led to conclude that they will

mutually hope to evince the justness of their opinions, and to increase the members of their

converts by the loudness of their declamations and the bitterness of their invectives.

An enlightened zeal for the energy and efficiency of government will be stigmatized as the

offspring of a temper based on despotic power and hostile to the principles of liberty.

Hamilton lets a reader infer that the partisanship of political parties corrupts the democratic process. He knew this 220 years ago. Most of the Founders did. The more partisan the parties, the less stable the nation.

That is the reason the Founders supported a constitutional republic over a democracy, to make the partisanship of the politicians less of a problem. The legal structure of the Constitution mandates the limits of political power and prevents the parties from changing the direction of the nation. Since we no longer have a constitutional republic, we need to let the political parties evolve into independent nations, or we take our chances in the no-man's-land of a volatile, paranoid public, and a second civil war.