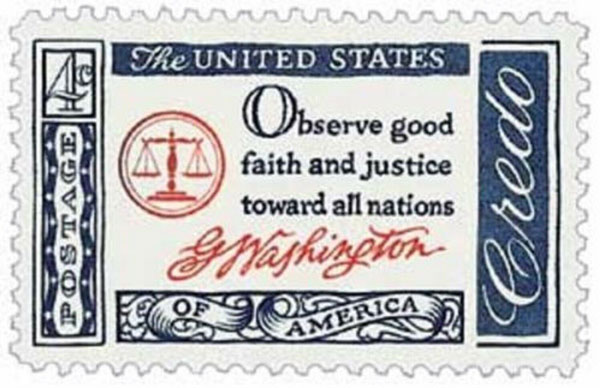

Founding Father Credo: George Washington

George Washington spent much of his life commanding the Continental Army of the future United States against the British Army and keeping the fight alive, and then serving the young United States as its first civilian President. The artists who designed the Credo stamp series did well to frame the Washington credo in blue and red, the colors of the Continental Army.

But the quote attributed to Washington—"Observe good faith and justice toward all nations."—fails to sum up the man, his beliefs, or gravitas. Any moralizer could talk about "good faith and justice". We hear stuff like that all the time. The quote is too generic, too laid back. So I prefer this quote from a letter that Washington wrote to James Madison:

We are united, or we are naught!—Like, "That's the end!" This is hands-on thinking. He defines unity and disunity as different camps. Friends and critics alike described Washington as a hard, stoical man, accustomed to the discomfort of the military life. He drove his men with a fixed sense of purpose and tolerated foolishness from no one. He shared the privations of his men, which earned him their undying loyalty, and he never lost sight of the goal of independence.

When the Revolution ended in an American victory, Washington expressed his wish to return home and tend to his plantation. But he could not do that, now. He had helped bring a new nation into existence and made it a hostage to fortune. Having worked so hard to bring the nation into existence; he had to commit himself to preserve it and his own legacy. His second-in-command Alexander Hamilton told him, "You will permit me to say, it is indispensible (that) you should lend yourself to its first operation." Hamilton knew Washington was a keeper.

Washington had proven himself indispensible on numerous occasions before—perhaps no occasion more critical than during the Newburgh Conspiracy. The conspiracy started in 1783 when officers and men of the Continental Army decided to mutiny. They had not received their wages for over a year from the cash-strapped, amateurish Continental Congress. For that reason, the mutineers wanted to force the Continental Congress to give them their back-pay.

Washington gathered intelligence on the mutiny, then confronted the mutineers and shamed them into abandoning their plan. He told them they should oppose anyone "who wickedly attempts to open the floodgates of civil discord."

Besides, he had a better idea—not a mutiny, but a second revolution to overturn the original organizational concept for the new nation, namely a Confederation—creating in its place a centralized federal republic, equipping it with constitutional protections and a tripartite government—executive, legislative, and judicial, and setting up a centralized banking system with a single currency. Hamilton and others coaxed Washington to attend the Constitutional Convention in 1787, guaranteeing that the Constitution passed.

Washington will always be a keeper; and when I think about the restiveness in modern America, the deep political divisions, and the risk of a new mutiny, I believe we need to remember Washington's watershed statements about unity. Before he left office, after serving as President for two terms, he gave a "Farewell Address". Thanks to him, every President since has delivered a farewell address—although none as memorable as his.

Just look at the figures. In the first thirteen pages of his Farewell Address, he used "unity" fourteen times. "The unity of Government which constitutes you (as) one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main Pillar in the Edifice of your real independence . . . your tranquility at home, your peace abroad, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize."

Washington knew that America's independence and strength depend on unity. Once Americans can retain it, they will never settle for less; and the only way we can regain it is to divide the Disgruntled, Disunited States and let the resulting nations govern themselves. A third revolution.