Founding Father Credo: Immanuel Kant

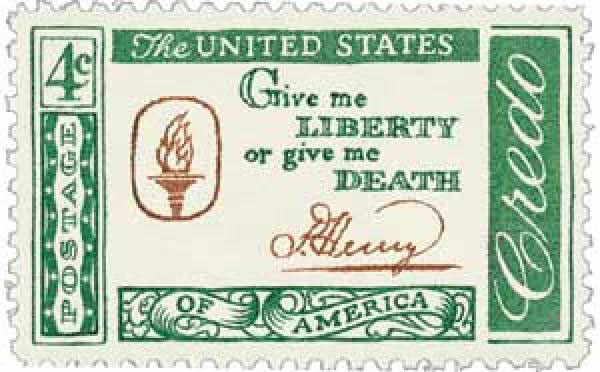

Patrick Henry started advocating American independence from Great Britain in the 1760s, with the enactment of the so-called Stamp Act, which required colonists to pay a tax on all printed matter. The colonists also latched onto the hated Tea Act, which required them to pay a tax on tea purchases. The administration of King George III insisted the government needed the tax revenue to pay off the debts from the Seven Years War, known in America as the French and Indian War.

In one speech, Henry suggested that someone assassinate the King of England. The quote in the Credo stamp series came at the end of a debate in St. John's Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virigina, he requested the funds to create a militia, in anticipation of armed conflict against the British authorities.

It is not too late to retire from the contest. There is no retreat but in submission and slavery! The war in inevitable and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come. . . . Peace, peace but there is no peace. The war is actually begun. . . . Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purhcased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

Other people before and since have stated similar ultimatums; but before we go along with Patrick Henry's, we want to know what he wants to do with his liberty. "Liberty" gives people a buzz, but without clarification, his ultimatum is too generic to carry weight in the world of competing causes.

He led Virginia delegates to support the revolutionary cause, and after that, the introduction of a new constitution, title the Articles of Confederation; but after three, their implementation caused so many problems, the Founders knew they needed some other foundational document, Henry could not reconsider his position or a more viable nationhood format. He continued his support of the Articles of Confederation and its emphasis on sovereign states and government at the state-level—leaving no more than a rump federal government.

The young nation's recent history had more than proven that the Articles did not work, and that the future of the recently-created American States depended on adopting a federal concept over the old confederation model; but Patrick Henry remained adamant and refused to support a federally-based constitution. He refused to give ground, even after the support for a federal model left him at the way-side. At wit's end, Thomas Jefferson wrote to James Madison that there was no way to deal with Henry, "except to ardently pray for his imminent death."

Henry and Madison had their showdown during the Convention, with Henry failing to convince the other delegates. Madison handled the debate the way he approached his other work—with a level of preparedness comparable to a trial lawyer's.

Henry tried to convince the delegates that the Confederation Congress had performed well, during the years of the Revolutionary War. Madison had to remind the delegates that this was completely untrue. Few of the States had supplied the necessary money and materiel to provide for the Continental Army, during the dead of Winter.

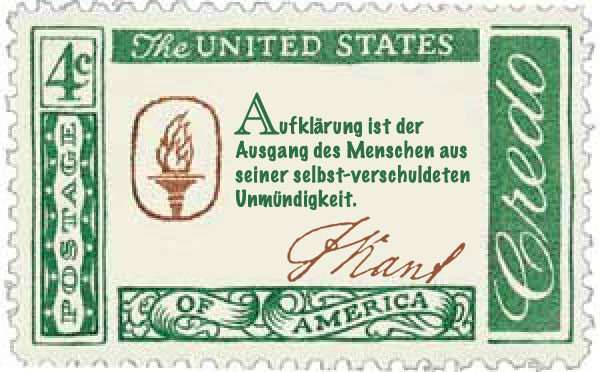

So in place of Henry, I decided to use Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher and proponent of the movement known today as "The Enlightenment." Few among the Founders had ever heard of Kant, or knew German. The well-read Founders like Hamilton, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison knew of the Enlightenment through English-language proponents like Isaac Newton, John Locke, and David Hume, and French proponents like Descartes, Pascal, and Montesquieu.

Kant came along near the end of the line of Enlightenment writers; but he was also one of its most important spokesmen. I include the Kant Credo in German. As a German-speaker, I can say that his words stand immutably. No English translation adequately sums up the import of his statement; but I will do my best to interpret it.

For one thing, Kant interprets "Enlightenment" as "Aufklärung". Lots of religious movments claim to provide enlightenment to their believers; so the use of "Enlightenment" gives off negative vibes for some people. In German military terminology, on the other hand, soldiers who do reconnaisance and intelligence-gathering are known as "Aufklärer". The personal initiative and spirit of enquiry that "Aufklärung" suggests for German-speakers defines it as forward-moving. You make determinations about your physical environment to give yourself the necessary information on how to proceed.

Kant says much more. He defines Enlightenment as a watershed in human development, inasmuch as, from now on, neither the royals, the church, nor even the government, defines the world for us. We do it ourselves. In fact, we have to do it ourselves. "The Enlightenment," says Kant, "gives man a voice and delivers him from his self-imposed lack of a point of view."

It does more than that. It summons mankind from a sort of pre-Enlightenment comfort-zone of enforced ignorance and stupidity. In the Enlightened world, the old theories about the world have to undergo empirical tests to see if they hold water; but even after the old theories fail the tests, many people remain loyal to them. The old theories and superstitions hang on in closed circles. The rest of us have to maintain an independent fact-finding faculty to serve as our guide. We cannot allow the blind and intellectually handicapped to intimidate us into submission. The Enlightenment has to serve as the Credo for people and institutions to define the world for us.

The Enlightenment is what America is all about—what Washington and the other Revolutionaries wanted. "Sapere aude!" said Kant. "Dare to know", or "Have courage to use your own powers of reasoning."