Founding Father Credo: James Madison

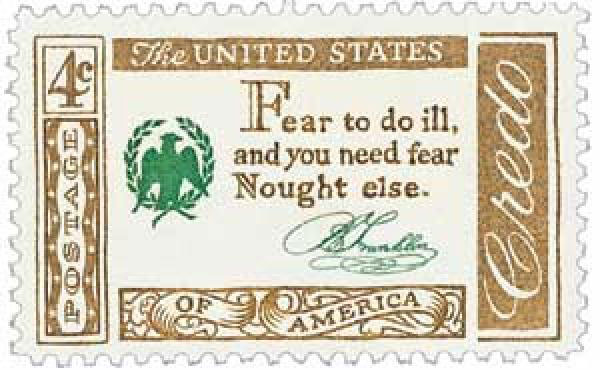

Benjamin Franklin's credo sounds like a generic, laid-back aphorism, spoken from a rocking-chair by someone's retired, church-minister uncle. Numerous academics try to paint Franklin as a sort of hippie-prototype, and he wasn't like that at all. You get a better idea of his personal convictions in Poor Richard's Almanack, published in 1733.

The pithy aphorisms of Poor Richard's Almanack don't really inspire me because they lack a personalized context. Good literature gives a person wisdom with a human face and perspective and a back-and-forth human dialogue, which the Almanack lacks. Here are a few aphorisms from Poor Richard's Almanack:

-1. At a working-man's house, hunger may look in but dare not enter.

-2. Diligence is the mother of good luck.

-3. God gives all things to industry.

-4. Industry gives comfort, plenty, and respect.

-5. Keep thy shop and thy shop shall keep thee.

Accordingly, modern Americans should see Franklin's Credo quote in the same context as the Almanack.

In his own "shop," Franklin invented the lightning rod, he established Philadelphia's prototype of a public library, and served as the young nation's first Postmaster General. He would appeal to Thomas Edison or Henry Ford, more than to Benjamin Spock or Linus Pauling. Having said that, the Post Office Department should have quoted something more interesting or personal in its take on Franklin.

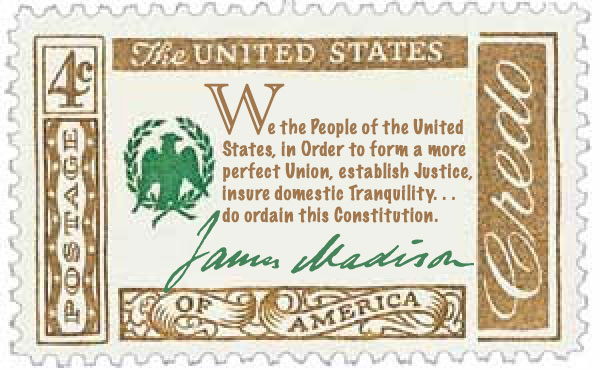

When I thought about redesigning the Credo stamps, I decided to eliminate Franklin altogether and use a quote from James Madison. Franklin supported the Revolution and signed the Declaration of Independence, but he had no further role in writing or framing the foundational documents that we use today.

Madison, on the other hand, basically wrote the text of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights, and then went through the arduous task of defending the documents against the States' Righters and their support of the failed Articles of Confederation.

Madison also wrote essays for the Federalist Papers, which laid down the framework of the new Federal Government. His contemporaries said he functioned less as a theoretician and more as a trial lawyer preparing his case. Like the other authors of the Federalist Papers, Madison understood the problems posed by a democratic government. Madison's words appeal to me especially now:

When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular government . . . enables it to

sacrifice to its ruling passion and interest both the public good and the rights of other citizens.

If Madison came back to life to read this quote aloud to die-hard Democrats and Republicans, they would deny such intentions and only point fingers at each other. Madison and the other Founders understood the human herd-animal well enough to guess his muddled intentions. Democracy alone does not protect a minority or an individual from the majority. A nation needs a constitution and a body of laws to assure our national survival, and there is not much we can do about the endless finger-pointing except divide the nation, so that Democrats and Republicans can operate independently in their own nations.