Freedom for Women is Fragile

Freedom for Women is Fragile

Dr. Marie-Luise Goldmann teaches in the Department of German Studies at New York University. Besides occasionally writing for newspapers, she also publishes high-end academic articles. Though their subjects vary widely, they mostly concern German-language literature:

- Ghosting: Narratives of Noncommunication in the Digital Age (studies of three modern German novels written by women);

- The Novella's Everyday Peril: Reflections of Jeremias Gotthelf's Die schwarze Spinne;

- "Gebannt! Gebannt!" Zur Poetik und Historiographie des Banns in Wilhelm Raabes Else von der Tanne.

Goldmann's article appeared October 16, 2022, in the Kunst & Kultur (art and culture) section of Die Welt, as noted at the top of the page. Putting poetic-license above common sense would make sense in the context of art and culture. People would see the photo of watermelon slices spilling on a woman's head in that light.

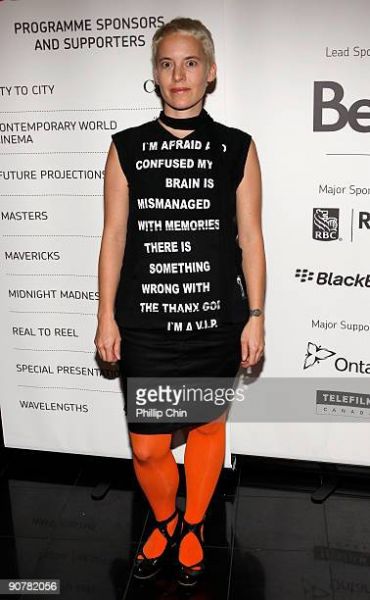

An emended version of the article also appears under the title "Why Freedom for Women is Still Endangered" on October 18th, under the section-heading "Machtfragen" (demands for more power). The photo of the reclining amputee in lingerie epitomizes the paranoiac nuttiness and vulnerability of radical feminism in scary terms. Who the hell are these people?

Goldmann based her "weibliche Freiheit" article on an art-exhibit by the feminist Candice Breitz in Basel, Switzerland. Goldmann pulls together the arcane forcefulness of Breitz's art to use for her own purposes. In her depiction of child-birth, the child emerges from the mother's womb, but does not like what it sees—"Testasteronismus" (testasterone-fueled terrorism)—and crawls back into the womb.

Breitz also exhibited her art in Wolfsburg, Germany, (home of the Volkswagen Corporation) under the title "Feminist Empowerment," along with fifty similar artists. "Im Zentrum," writes Goldmann, "steht die Frage, wie Unterdrückung in Macht zu transformieren ist." I speak German, but honestly, I am not certain what this sentence means. I have enough trouble understanding American feminists like Naomi Wolf. It seems to ask, can feminists transform oppression into empowerment? I always need to ask a counter-question: "Why are these angry, defiant feminists still here?" Don't they want their own country?

Women pelted with watermelon slices and amputees in lingerie do not transform easily into a wish for nationhood, as much as they suggest more browbeating and arm-twisting to get stuff from the males—stuff that they should get by their own efforts.

With my available information, I can only conclude that timidity, dependence, and existitial angst—not feminist striving for self-determination—drive Goldmann's article and Breitz's exhibits to take such a hostile stance toward males. We are supposed to be partners! The males received their traits from nature—concern for creating safe habitats for families, having enough balls to father children for a new generation, and an acquisitive instinct to provide for them—not this crazy stand-off that the feminists propose.

How in the hell can Goldmann demonize the male mindset and his sexuality—which she describes as "Testasteronismus," as if testasterone is the enemy of women. Maybe she would rather women have children by artificial insemination, if they want children at all. Besides all the other traits that I ascribe to Goldmann, let me add envy and neurosis. There is simply no excuse for a professor at a state university to hold such views.

Die Welt is Germany's most important conservative newspaper; so I wondered why it published her articles. Maybe Die Welt deems Goldmann less influential—more easily dismissed than a thoughtful, analytical feminist.