From the Old Economy to the New Economy

Bill Gautsch, stone-mason

I have an old friend in Greenville named Bill Gautsch. I speak German and recognized "Gautsch" as a German name. I also know that many Germans, and by extension, Americans of German descent, take their names from the professions that their ancestors practiced. A Gautscher in Medieval times participated in the manufacture of paper. John F. Goucher, founder of Goucher College in Maryland, descended from a German immigrant who gave his name to the immigration officer, and the officer spelled it phonetically on the immigration form.

Bill Gautsch's Medieval ancestor may have been known as Wilhelm of Darmstadt. Wilhelm had a friend Otto of Darmstadt, but when Wilhelm joined a paper-making firm, he changed his name to Wilhelm Gautsch. Otto, on the other hand, started working at a brewery—"Brauerei" in German—and changed his name to Otto Brauer. An American immigration officer may have anglicized his name to "Brower." David Brower, for instance, served as the contentious director of the Sierra Club for many years, and was an accomplished mountain-climber.

Gautschen eines Druckerlehrlings 2004 in Düsseldorf

In the first photo, honorary members of the printers-guild re-enact the initiation for a new member, with a ceremonial dunking to replicate the member's participation in the manufacture of paper; but in the old days, when the guilds ran everything, the initiation involved a clear act of submission to the authority of the guild. The guilds, in turn gave Wilhelm and Otto a sense of organization and an identity. They took care of their members, but also limited their members' ability to rise in society, or gain any independence from them.

from Wikipedia article

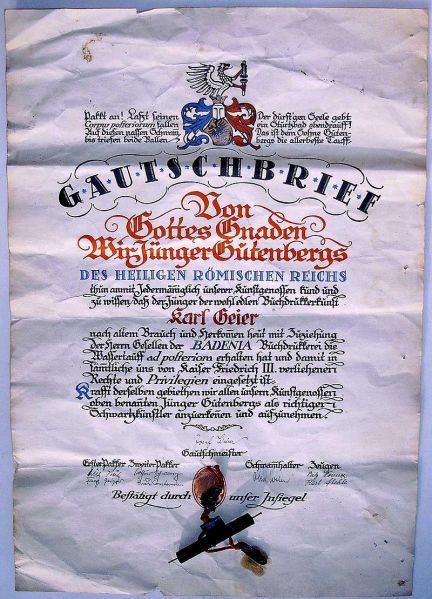

In the second photo, the newly-inititated Gautscher receives a "Gautschbrief," a certification that he has proven his ability in the manufacturing of paper. With that document, he could move anywhere in Germany and obtain employment as a Gautscher.

My great-great-great-grandfather lived in Erfurt, Germany. In his letters, he complains that Prussia took over the leadership in Erfurt and instituted something called "Gewerbefreiheit," or freedom of professions. After Gewerbefreiheit, anyone could start a business. They didn't need to belong to a guild; and if they could hook up with a venture capitalist, the capitalist would help underwrite the business-owner's need for equipment and expansion. That connection of entrepreneur and capitalist became the basis for industrialization, the new mode of manufacturing.

With the power of the guilds depleted, the people who had depended on them as the basis for their livelihoods lost out. The guilds no longer had the means to support them. With nowhere else to turn, they could take a factory job, surrounded by people they didn't know and had no human connection with, they could do as my great-great-grandfather did and immigrate to America to start a new life, or they could join one of the revolutionary cells cropping up to protest their poverty. Indeed, a poll of the participants in the Revolution of 1848 revealed that many had held positions in the guilds and had lost their livelihoods as a result of industrialization.

Each "New Economy" does that. It displaces the people who had done okay in the old one. A "New Economy" today does not create the poverty and displacement of great-great-grandfather's time in Germany, but displacement of the "Old Economy" causes a loss of status and personal dignity for many, and creates a lot of resentment toward anyone successful in the New Economy. Much of the resentment shows up in places like Facebook and even carries the Marxist message propagated by Karl Marx. His publication of Communist Manifesto in 1848 set in motion the Revolution of 1848, and the defeated guilds provided the manpower for it.