German Newspaper Photos

If German-newspaper publishers obscured the text of their articles and revealed only photographs, the average American reader would not know what to make of them. German newspapers reaveal a consciousness of history. They take the reader back in time, so the reader knows where history has taken the nation. They keep us mindful of historical events and characters.

In the first photo, you see a woman sit on top of a Volkswagen Beetle, pulled along by a horse with a license-plate that reads, "PS1 BRD." In German, "PS" means "Pferdestunde." the German word for horse-power. Exactly one horse-power pulls the VW. You can see the single horse for yourself. BRD stands for Bundesrepublik Deutschland, the formal name for West Germany, until the fall of the Berlin Wall and Germany's Reunification.

Although humorous, the image also recalls Germany's experience during the Oil Embargo of 1973, when the Arab nations imposed an embargo on sales of oil to Western nations, for their support of Israel. For all the damage the Embargo caused the West, the loss of oil revenue must have severely impacted the Arab perpetrators, since they had nothing else to export, no other source of income. Other nations gladly stepped in to supply oil in their place.

My college-roommate's brother served in the U.S. Army during this time and remembered his unit's trips on the empty German Autobahn, that haven for speedsters from around the World—emptied by the actions of Arab nations. People were desperate enough to dispense with the car and recruit the old family nag, hang a license-plate around his neck, and put him to use.

During the dark days of the Covid-19 Lockdown, the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) ran a six-hour documentary about Ernest Hemingway, hosted by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, that explored every aspect of Hemingway's complex life. The PBS doc seemed to favor Hemingway's less noble actions and his infidelities to women. I admire the man, since he clearly lived life to its fullest and opened himself to a variety of experiences that changed his life, and ours by reading about them. Hemingway may rank as America's greatest writer, ahead of his time in literary style and in breadth of experience.

After you read Farewell to Arms, who one can forget the confusion of combat, making death such a commonplace experience. Hemingway served as an ambulance driver in Italy and served with the Italian Army. His irreverence and attention to detail make it unquestionably the most greatest book about World War I, enough to get it on the Nazi book-burning shit-list.

The Sun Also Rises hardly justifies the term "fiction," since it recalls so vividly Hemingway's post-war experiences as a journalist in Paris. Before he eats supper, Jake Barnes picks up a prostitute so he won't have to eat alone. The prostitute tries to flirt with Jake, but he fends her off and explains that War-injuries have left him impotent. Jake functions like a man in denial of PTSD, running on empty, trying to fill his tank with booze—getting tanked night after night.

Living in Paris after World War I must have tried his patience. Imagine eating at a restaurant high enough above the ground, that you could actually parachute back to Earth. Talk about living on the edge! Not the best place in the World for a man with PTSD. But Hemingway never shied away from living on the edge.

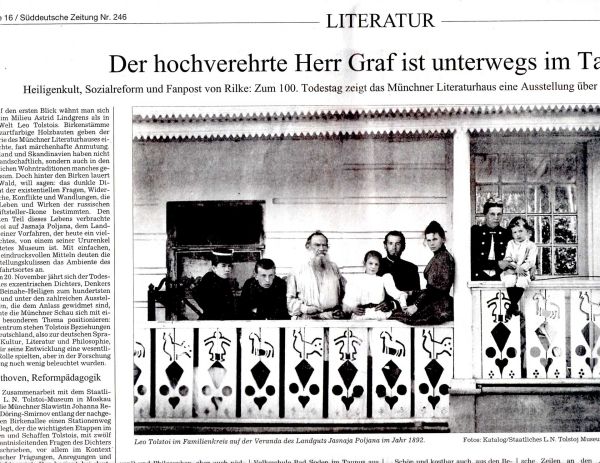

This photo shows the author Leo Tolstoy at home with children and grandchildren, looking aged and grizzled, and wearing peasant costume. Tolstoy actually died in a railway station near his home, and someone drew a profile on an interior wall of the station, showing the dead Tolstoy lying in his deathbed, that remains visible to this day.

I can remember my elation, when I read Anna Karenina, of the nobleman Konstantin Levin taking off his jacket, fetching a scythe, and joining the peasant-serfs cutting hay. In manual work, he found a communing of spirits with the serfs, who watched with misgivings their master engaging in work that was beneath him. When I went to work for my father and had men working under me, I looked for a similar communing of spirits in manual labor. I never found it, but I remember the hay-cutting scene as an enduring personal ideal.

More than that, I remember Tolstoy's human networks, friends, family, and colleagues at work, and the relationships they had. I remember the level of honesty revealed in spontaneous conversations that run for entire chapters—a drop in the bucket of Tolstoy's thousand-page novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

As a writer, I have never wanted to do more than to bring to life characters with the same integrity and personality as Tolstoy's. I remember coaxing a girl-friend to tackle one of Tolstoy's thousand- page novels. She read Anna reluctantly but said to me afterward, "Tolstoy knows women."