German Newspapers, part I

The New Kissinger Book

This article ran in Die Welt German newspaper on July 8th, 2022, to introduce a new book by the 99-year-old former statesman Henry Kissinger, titled Leadership: Six Lessons surprised me. I didn't even know that he was still alive—99 years old and still writing!

I read an excerpt of it in the Welt article when I was in Germany, and without having seen the actual text of the book, I will translate a portion of it into English, as it appeared in the article, starting with the very first line:

Most leaders do not have the capacity for visualizing the future. They work from a well-defined job-description, which involves mostly maintaining day-to-day business achored in the context of the status quo. . . .

The limits of such leaders appear during crisis periods—war, for instance, or radical changes in technology and industry. Trying to treat these issues with mere managerial technique, to blindly maintain the status quo against the upheaval, can have disastrous consequences.

Thanks to our democratic system of government, transformational leadership emerges to either mend the status quo, or replace it. . . .

Informed statesmen understand that they basically have two continuing tasks:

- Protect the functioning of the society. Statesmen must promote better functioning when they can and monitor its parameters;

- While creative thinking helps the society advance, it should not alter the basic character of the society. The society maintains its core values and orientation.

During my college years in the early-1970s, few figures in national politics stirred more controversy than Dr. Henry Kissinger. His presence in the Nixon and Ford administration carried more influence than any other official. His high-handedness made him plenty of enemies, but he accomplished a lot during his tenure at the State Department and the National Security Agency.

Kissinger, left; Vice-President Nelson Rockefeller, center; President Gerald Ford, right

With his pronounced German accent and restrained continental manners, he invited impersonation from a variety of actors and detractors. John Belushi does one of the best for Saturday Night Live, sitting for an interview with Barbara Walters, played by the actress Gilda Radner. Radner imitated Walters' speech impediment hilariously, introducing herself as "Baba Wawa."

Washington Post journalist Robert Timberg writes about American foreign policy at the end of the Vietnam War in The Nightingale Song, published in 1995. Timberg himself served in Vietnam in the Marine Corps and writes that military servicemen returning from Vietnam accepted important positions in the National Security Agency and the State Department. One serviceman, Lt. Colonel Robert McFarlane, remembers meeting Kissinger for the first time when he joined the NSC. Kissinger spoke curtly and almost dissmissively: "Are you willing to work like crazy for no reward whatsoever? . . . You know, I'm not in the business of hiring self-promoters."

Imtimidated, McFarlane answered, "I'll do my best, sir," or something like that. He really does not remember how he answered.

A colleague later asked McFarlane, "How'd it go?"

"He didn't say anything positive," said the dejected McFarlane.

"Did he say anything negative?"

"No."

"Then you're in. He (Kissinger) never says anything positive." No one who worked with Kissinger had better than mixed feelings toward him. As a statesman, he moved by his own drummer—as a strategist of historic proportions—brilliant, scheming, and ruthless. His doctorate at Harvard, titled "A world Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh, and the Restoration of Peace," lets everyone know he thinks globally.

Behind Kissinger's back, McFarlane "did a terrific Kissinger impersonation," friends told Timberg, but in those days, "Everybody did good Kissinger."

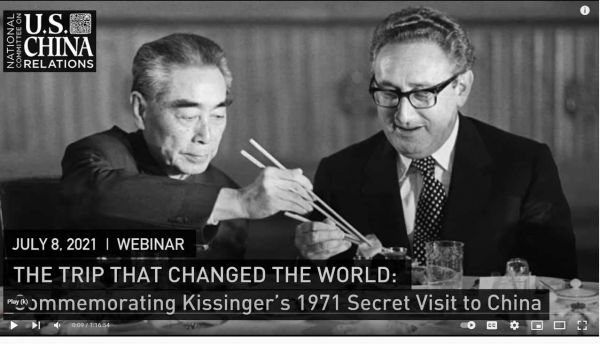

More seriously, Timberg writes that, "On orders from Kissinger, . . McFarlane . . . passed highly sensitive intelligence on Soviet ( war) capabilities" to the Chinese. "In return, the Chinese 'gave us access to invaluable sites for intelligence gathering on the Soviet Union.'" The fact that the Soviets

had to maintain a military against two adversaries drained their treasury. "However, had Congress known about the exchanges," Timberg writes, "they would have been immediately curtailed."

Timberg writes that McFarlane got to know Kissinger well. He knew that Kissinger had "withheld information from Congress. . . . Yet in doing so, he undeniably nurtured a relationship of profound importance to our security. The Nixon-Kissinger strategy to outflank the Soviet Union . . . was a historic stroke of geopolitical wisdom."

One may disagree with Kissinger's ideas, or mistrust him for his actions while Secretary of State; but we can still marvel at his ability at 99 years of age to write so well.