German Newspapers, part III

Boys Risking Everything

I grew up in a neighborhood full of children who were in and out of our house all day, so that none of the mothers locked their doors. We played games all day during the Summer and got our share of scrapes and bruises, but we grew up with a social consciousness—social in the sense of, or opposite to, a solitary consciousness. Baseball and football games were fun and sweet, even if they did not amount to much. Dad played football coach. My mother's cook worked as pitcher. If I feel an ease about dealing with people, it must grow out of my experience of growing up so socially.

That all changed when I reached high school. In high school, you played football in shoulder pads, a helmet, and cleats—and you needed them. You didn't just get scrapes and bruises, you could get sho-nuf beaten up. The other team's players wanted to knock you on your ass whenever they could. Even pick-up football games in the park involved some unnecessary roughness.

Reaching puberty, having all that testosterone surging through us, getting our first adrenaline-rush from doing something risky, escaping injury, and bragging about it to our friends—that was a big deal then. I never thought of it as flirting with death. I never thought of myself as suicidal, playing the risk-all type jackass. Flying down a mountain road on my bicycle, going 120 mph in my BMW, climbing a tall tree, climbing a steep mountain—it was just fun. I had an internal sense of the level of risk I wanted to take. I didn't do anything foolhardy.

Other boys would do anything—to get a laugh, attention from girls, or outdo their peers. Here are a few examples of their prowess. As one critic expressed it: "There's not enough mustard in the world for these hot-dogs!"

The article's title, "Männer kosten ein Vermögen" translates to "Raising Boys Costs a Fortune," to the society. The author Caroline Ferstl includes some statistics about boys in Germany and all the craziness they get up to—65 billion dollars worth.

Included in the expense of raising boys includes:

- juvenile incarceration;

- drug addiction;

- domestic battery;

- gambling and day-trading;

- extra school tutoring;

Billions of dollars spent on boys who hurt themselves and others. And if all that isn't bad enough, the boys grow up and become executives, and don't hire enough women. They preserve the sexual inequality of boardrooms and executive staffs; and political men don't promote enough women to stand as candidates.

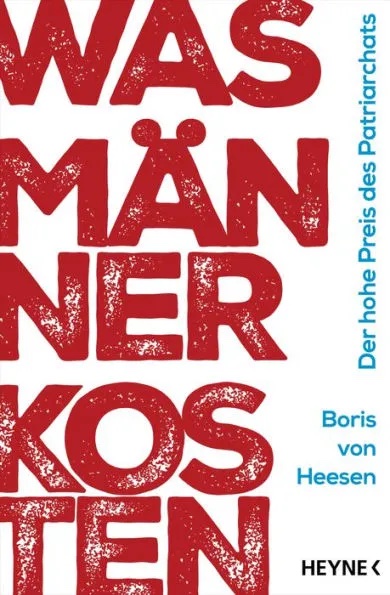

All this negativity about the male sex appears in a new book by Boris von Heesen, Was Männer kosten. Caroline Ferstl's article basically critiques von Heesen's sweeping conclusion, that men do all the damage, that men cause all the problems of the society, that they do nothing redeeming for the society, and that women have to do all the work of cleaning up behind them.

Ferstl's article also questions von Heesen's arbitrary measures to the problems men cause. She says the measures work against the principles of a freedom-loving society. They regiment life in a way that most people—men and women—would find unbearable.

Ferstl also draws attention to gaps in von Heesen's view of men, because men create most start-up businesses in our country, furnish most of the start-up capital, and develop most of the gadgets that we take for granted.

Women start relatively few businesses—11% of the total number of new businesses in this country. When women do start a business, their lives become fodder for all kinds of criticism and ridicule; so most women get the drift and don't even try. There are also fields of work that women would not touch with a ten-foot pole: cleaning sewers, cutting down trees, fighting forest fires, not to mention the military and military-related industries—that employ almost entirely men.

Ferstl writes that von Heesen will have a time trying to promote his book. Ferstl describes a typical feminist bookstore, with tables and shelves already sagging under the weight of combative feminist publications, each trying to stand out from the others.