Go Back to Church, part I

Go Back to Church, part I

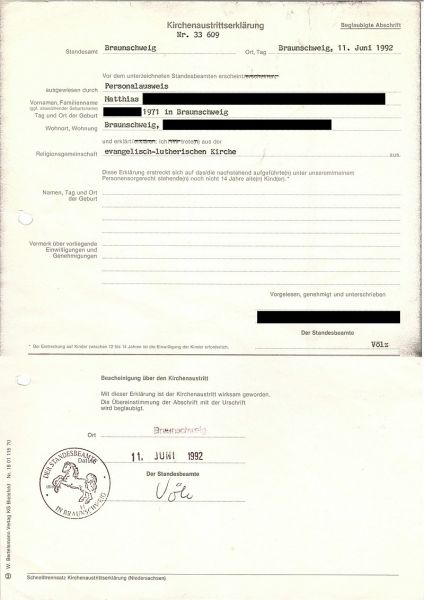

This article appeared in the Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper on July 1, 2022. "Die nachchristiliche Generation" (the post-Christian generation) reports on the increasing number of Germans who declare themselves non-believers, withdraw their membership from the church, and opt out of paying a federal church tax for the maintenance of religious buildings and schools. To exempt themselves from the church-tax, they receive a "Kirchenaustritts-bescheinigung," a certificate from the government that declares them officially "Unchurched". If an tax-official catches them attending a church anyway, can the government invalidate the Kirchenaustrittsbescheinigung and make them start paying the church tax again? The article does not say. See below a typical Kirchenaustrittserklärung, which declares a person's intention to leave the Church.

I no longer read the Bible, pray, or go to church myself, but I don't think I could go as far as to officially unchurch myself. My point-of-view remains essentially Christian, inasmuch as I still love church-music and church art. I also believe that the church culture influences one's personal philosophy, doctrine, and sense of unalterable truth, whether God exists or not.. The church defines a person, and human-kind needs that self-definition, needs a form of corporate identity. Pastors, priests, and the Bible dictate that members shall celebrate their faith communally, so that they can maintain a sense of direction and strengthen their disciplined approach to life. Church leaders warn against acting like lone-wolf Christians.

Human beings should recognize their limits. A value-based life needs encouragement from time to time, wheher you remain a practicing Christian, Buddhist, or whatever. Humans need a doctrine and some instructive materials to help them interpret the insights of the doctrine, whether you make the Desiderata of Max Ehrmann, The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran, or On Walden Pond by Henry David Thoreau the source of doctrines that tells people who you are. Say what you will about Christianity, church attendance shods people in sturdy ideological boots and gives them an orientation to life that makes them willing to risk death for their faith. If you opt out of church, you might as well say you're opting out of the future.

If non-believers have nothing to take the place of Christianity, no philosophy to fall back on, they might want to consider going back to church—God or no God! Someone has to remind you who are, who your friends are, what your enemies look like, to give you a sense of direction in order to keep you moving forward going, and to keep you mindful about your personal values in the hub-bub of daily life—since you are likely to forget, under pressure from others.

I also recognize that religious faith has to co-exist uneasily with an individual's intellect. He has to process experiences and sermons to some extent empirically, even if he doesn't consciously think about it. As the unchurched writer Artur Koestler reminds us, "Faith is not only capable of moving mountains, but also making you believe that a herring is a race-horse." The tension between the two poles may aggravate us. It also defines us as people. So, a forward-thinking person has to assume both.

Without a personal philosophy, or faith in something, we make ourselves vulnerable to authority figures. With no one to define your orientation, the authority figure will define you. You will be better off with the God-or-no-God church than you will with an authority figure. He hectors you from the chip on his shoulder; and his persistent resentment will gradually make you follow his orientation rather than your own. His resentment will turn you against wealthy people, insurance companies, Jews, Blacks, your own country, or some other target. He convinces you from out of his hurt, rather than from his contentment with his life, and shods you in his doctrine, so that soon you will parrot his invective.

This scenario comes out in the novel The Walking Stick, published in 1964 by the British novelist Winston Graham, better-known for his Marnie and the Poldark novels. The Walking Stick tells the story of Deborah, an antiques-appraiser, who falls in love with Leigh, a frustrated artist in London, England. In the movie-still from 1970, Samantha Eggar plays Deborah. David Hemmings plays the charming Leigh.

Leigh rants about the power of wealth, how the wealthy hinder starving artists like himselt, and how capitalism exploits the poor, etc. etc. Sound familiar? Leigh proposes to dish out a measure of payback to the wealthy, and asks Deborah if she will help him and his crew rob the auction-house in London where she works. She has misgivings about it but agrees out of sympathy for Leigh. Her misgivings and sympathy work against her sense of right-and-wrong in this remarkable story. It would help, of course, to have a community of believers supporting her but, with few friends, she has to go it alone. Her ambivalence, the risk of losing the only person who appears to care about her, and her nagging doubts about Leigh's crew sound very familiar to me.