Hoffer and Conservatives

I had a curious feeling when I started studying the history of political philosophies and economic models. Most intelligent or engaged Americans identify themselves as "Liberal" or "Conservative", or politically Left and Right. But "Liberal" in the late-19th century referred to the burgeoning new class of wealthy entrepreneurs, who benefited from the capitalization of industry. Liberal politics defined the freedom of a citizen to start any business he wanted, without government permission. He only had to purchase a business-license.

The Swiss political party, "die FDP, die Liberalen", started life as "die Fresinnigen Demokraten". The archaic german word "freisinnig" means "liberal-minded", or "orientated toward freedom". In Germany, the Kaiser implemented a similar policy called "Gewerbefreiheit", meaning any citizen could start his own business. "Gewerbe" means profession or occupation. A man could choose any business he wanted and did not need royal sponsorship.

On the other hand, a "Conservative" in the nineteenth century meant a supporter of the monarchy, the aristocracy, the Church, and the military. The nobility with its vast land-holdings depended on the peasants to till the land and to pay taxes to the nobility. When factories in the cities of Britain and Europe promised a better life for the peasants; they relocated en masse to the cities, leaving the nobility to fend for itself.

The British writer Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a description of a destitute aristocrat in his Sherlock Holmes story, "The Adventure of the Speckled Band". The Roylott family "was at one time among the richest in England, and the estates extended over the borders into Berkshire in the north, and Hampshire in the west. . . . Nothing was left save a few acres of ground, and the two-hundred-year old house." About the house, Conan Doyle writes "In one of the wings, the windows were broken and blocked with wooden boards, while the roof was partly cave in, a picture of ruin."

The working class may have resented the pushy entrepreneurs and their restless work ethic, but I doubt their resentment compares to the hatred that the aristocrats, living in their ancient, dilapidated homes, felt toward the entrepreneurs. British aristocrats like Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, and Guy Burgess got revenge against the entrepreneurs by joining the Communist Party and spying for the Soviet Secret Service—against the entrepreneur class.

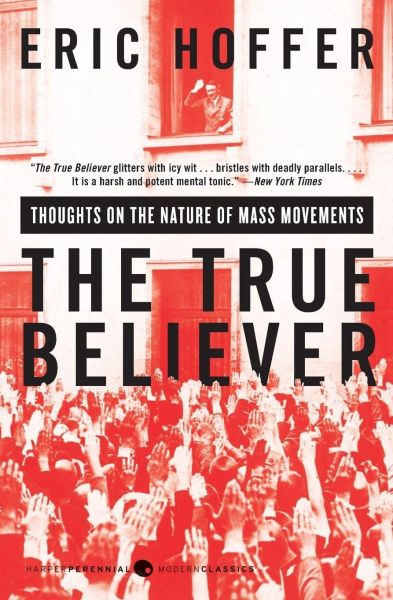

Eric Hoffer expresses an interesting ambivalence toward conversatives in his book True Believer: In Axiom 51, he writes,

The well-adjusted make poor prophets. . . .

A pleasant existence blinds us to the possibilities of drastic change. We cling to what we

call our common sense, our practical point of view. Actually, these are but names for an

all-absorbing familiarity with things as they are. The tangibility of a pleasant and secure

existence . . . makes other realities, however, imminent, seem vague and visionary.

The conservative's unwillingness to respond pro-actively to threats bothers me. Hoffer explains the problem, saying "The conservative doubts that the present can be bettered, and he tries to shape the future in the image of the present. He quotes one historical figure saying, "I wanted the sense of continuity." Hoffer continues this thought into Axiom 54. "People who live full, worth-while lives are not usually ready to die . . . for a holy cause." In an end-note to Axiom 54, he writes,

There is an echo of this disconcerting truth in a letter from Norway, written at the time of

the Nazi invasion: "The trouble with us is that we have been so favored in all ways that

many of us have lost the true spirit of self-sacrifice. Life has been so pleasant to a great

number of people that they are unwilling to risk it seriously."

Perhaps, instead of zoning out with Netflix in the evening, a few Republicans will take Hoffer's warnings seriously and think more deeply about our future as a nation