How to Increase the Entrepreneurism of Women

How to Increase the Entrepreneurism of Women

This article appeared in the Sunday edition of Die Welt newspaper on 26 November, in a special section titled "Better Future Conference." The article bears the title "Wachsen aus eigener Kraft," which translated into English means "Growth Through our own Efforts." The Conference's promoters wanted to discuss the ways and means of involving more women in business start-ups and ownership.

But two big oversights hobble the intentions of the article. Firstly, a man writes it. Why not assign the article to a woman for consistency's sake? Secondly, the article begins with a confrontational statement from the feminist-activist Niddal Salah-Neldin, during her opening speech for the Conference: "Talent and achievement are not attributes peculiar to men." That statement is pretty tame compared to other statements Salah-Neldin has made. She wanted others to understand her level of authority: "Ich bin kein Zirkus-pony!" or in English, "I am not a circus-pony!" She also made it clear that she intends to alter the status of the "Boys-Club" who control everything. She also said that a woman should not subordinate her career to children and house-hold chores.

I know Germany pretty well, and I know that Germany has a discouraging number of men and women who never marry. Such challenges as one hears from feminist-activists do not help the sexes grow closer. The only concerns she addresses involve competing power-issues, not opportunities for women in the business arena. I just keep thinking--Hell! The two sexes should work as a team, not as competing near-enemies. It reminds me of the verse in the Song of Songs that refers to "the little foxes that spoil the vineyards of love."

So, I had to ask myself what Salah-Neldin and people of her ilk really want. From a young age, my father asked me what I really wanted to do with my life. As I grew older, his questions became more insistent. My replies only reflected my age and level of consciousness, which showed that I was no high-falootin' genius. My ineffectual replies never bothered Father. He continued to pose the question to me, and he wanted me to keep posing the question to myself.

Salah-Neldin does not do this, but harps on the fact that only 21% of businesses are started and owned by men. Instead of asking women if this disparity really bothers them, she should ask them, "What do you really want to do with your life?" Pose the question mostly as a confirmation of freedom and volition.

Many women will probably answer, in all honesty, that they prefer to sing for their supper, and will do whatever it takes to gain acceptance, so that they can chow down in peace. Give them a recognized standard, a career-bar, and they will strive to jump through whatever hoop is offered them; but away from the frayed fabric of the divided culture, most will say they want nothing more than to marry and raise a family.

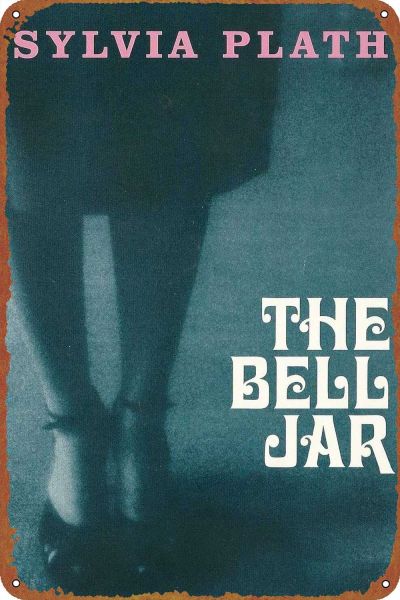

The author Sylvia Plath ponders this dilemma in her novel The Bell Jar, published in 1963. Her main character Esther Greenwood works as an intern for an important women's magazine in New York. Esther's superior at the magazine appears perplexed by Esther's hard work. Esther seems to lack personal motivation; so JayCee asks her pointedly, "Doesn't your work interest you, Esther?"

Dutifully, Esther answers, "Oh, it does. It does."

JayCee continues, "What do you see yourself doing in five years?"

Esther answers in a disembodied voice, "I don't know." She tells her readers that she has worked hard all her life to make straight-A's and to perform better than anyone in her class. She attends college on a full scholarship. All her life, she has done little else but impress other people who might help her. But this toilsome position does not make her like them much, because she lets them define the scope of her life.

Put under pressure by people like Salah-Neldin, most people will say that they will do what they must to earn their supper, but like Esther, they do not regard a pushy woman like Salah-Neldin with personal warmth. In the culture of activist-feminism, events like the "Better Future Conference" employ watchers to look for disaffection among the attendees and question their motives for being there. If pressed, the attendees will probably say they need someone to push them, to get themselves off the hook.

Rather than act confrontational toward boys, whom they mostly do not know anyway, or worry over abstracts like the disparity in business start-ups or the mathematics of hiring quotas, Feminists should ask themselves what market they want to exploit and go for broke. What new products or services can women offer the public? Can they offer them faster, better, and cheaper? Services and products define the free-market establishment, not gender-hostility or quotas.