Intimidation

Intimidation in 1984

George Orwell's dystopian novel 1984 disturbed me more than any book I encountered during high school. The presentation of a futuristic, dictatorial society was a lot to swallow for an upper-middle class white kid who grew up in the South. Long torture sessions define the second-half of the novel with an immediacy that still gives me the heeby-jeebies when I read it.

In 1984, government officials in a futuristic, dystopian society use Thought Police to defeat dissent and assure the smooth implementation of public policies. They understand that they have to defeat dissent at its origin—an individual's thought process. Everyone should stay so busy, he doesn't have the time to think deeply about anything. The occasional violator undergoes reconditioning until he no longer poses a threat.

A man named O'Bryan directs the torture of a hapless, middle-aged, government employee named Winston Smith, a low-level paper-pusher. The Thought Police had learned that Smith kept a diary to record his frustrations and anger the restrictions. The Thought Police kept Smith under surveillance until he incriminated himself, then took him into custody.

Orwell uses his literary skill to make the reader feel Smith's pain; but the Thought Police don't just want Smith to confess his crimes or to repent. They want to adjust his perception of external reality.

The accoutrements of the modern torturer—shackles, electric "muscle," and endless interrogations, it's all there. On page after page, the reader feels the torture of Smith. How the book has maintained its level of popularity bewilders me.

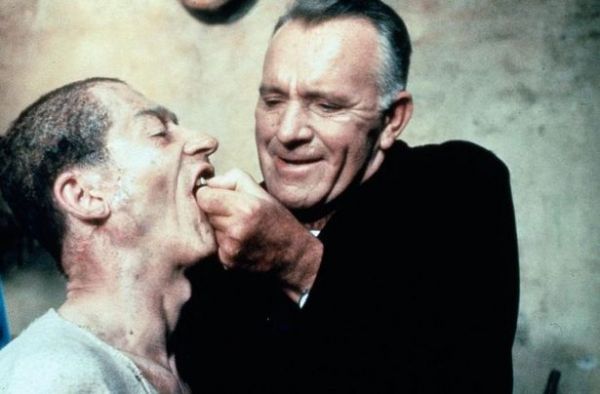

Considering the impact 1984 has had, it has spawned only two unremarkable movies. The director Michael Radford directed the second film in 1984, with John Hurt as Winston and the incomparable Richard Burton as O'Bryan. Burton plays the role of O'Bryan as a sadist, rather than the brisk, efficient government bureaucrat that Orwell intended.

O'Bryan's job is to enforce the society's political correctness to a bizarre degree. The Thought Police attach "two soft pads, which were slightly moist" to the head of Winston Smith. O'Brien turns a dial and causes him a lot of pain, then he holds up his hand and asks,

"How many fingers am I holding up, Winston?"

"Four."

"And if the Party says that it is not four but five—then how many?"

"Four."

The word ended in a gasp of pain. The needle on the dial had shot up to fifty-five. . . .

"How many fingers, Winston?"

"Four."

The needle went up to sixty. . . .

"Four! Four! What can I say? Four!"

The needle must have risen again. . . .

"How many fingers, Winston?"

"Five! Five! Five!"

"No, Winston, that is no use. You are lying. You still think there are four."

There is no question about breaking. You will break, no matter what. And you cannot fool O'Bryan. He can nearly read Smith's mind. Orwell presents him as a perverse psychologist, who can observe Smith's thoughts just by looking at his face. But he is not a crazy outlier. He's a government official who enforces policy. He is not interested in making Smith confess to anything, because Smith has not know anything. All O'Bryan wants is to break Smith. So, on into the next chapter, he continues the torture.

Eventually, O'Bryan reveals his reason for the torture: destroy independent thought and alter one's perception of reality; and at the end of the long, hard, torturous road, he succeeds. He overwhelms Smith's faith in his own perceptions:

"O'Brien held up the fingers of his left hand. . . . "There are five fingers. Do you see five fingers?"

"Yes."

And he did see them for a fleeting instant, before the scenery of his mind changed. He saw five fingers, and there was no deformity. Then everything was normal again, and the old fear, hatred, and bewilderment came crowding back again.

I reacted as you might expect, with grief and disgust at the abject humiliation and emasculation of a man, faced with an enemy who has unlimited resources to hurt him. I also call the reader's attention to O'Bryan's goal—to make Smith see reality the way O'Bryan wants him to see it. Just a few more "treatments," and Smith will believe anything O"Bryan says to him.

On one level, Smith will appear completely normal, but if the media tells him the sky is brown, he will believe it. So that if someone asks him, he will glibly point to the sky and say it is so. He will be adamant about it. O'Bryan's torture of him may fade in his memory, but he'll know better than to think for himself again. He'll know to let the public-media do his thinking.

A government official like O'Bryan can employ many procedures to break a person's will, and they don't all involve physically torturing him. O'Bryan uses the old-fashioned way, by causing physical pain, but other methods break a person just as effectively, such as deconstructing him. The torturers will undermine his selfhood and empty him of personality and will. Shrewd leaders understand that the public does not really know anything. It hasn't the time or inclination to inform itself. It only has time to maintain a rag-bag of disorganized clichés.

If my reader wants to know more about that, he can read a quality work of fiction, by Harold Pinter, for example. Popular writers do not like to tell the truth unconditionally, as it will end their careers. In any case, they would never say it as bluntly as Pinter does.

Harold Pinter: The Birthday Party

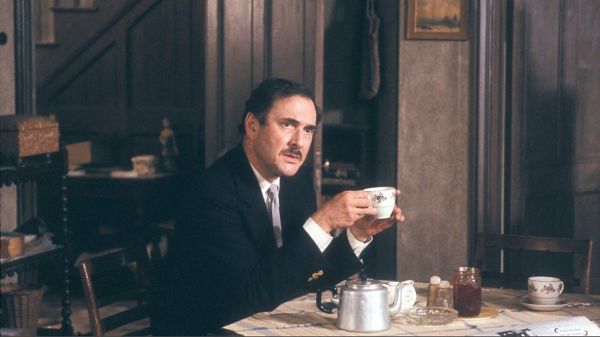

My reader can consult YouTube for two performances of The Birthday Party. Pinter himself appears in one production, filmed by the BBC, that appeared on the TV.

The late Patrick Magee and Robert Shaw starred in another filming of The Birthday Party directed by American William Friedkin. The story concerns a slovenly, solitary man named Stanley Webber, who lives in a seedy boarding-house in an English coastal town.

Two strangers named Goldberg and McCann also get a room there. The have a contract of sorts to ruthlessly break Stanley, for reasons not known. Their deconstruction of him causes him to suffer a nervous breakdown.

Some critics of The Birthday Party, questioned Pinter's using a Jew and a Catholic as the torturers. Pinter explained that he used them because Judaism and Catholicism are the two most dictatorial religions in the world. One can excuse him for excluding Islam in his assessment, but he lived and died before the era of radical Islam.

The creepy plot of Birthday Party frightens the viewer because Pinter does not let him understand why Goldberg and McCann want to break Stanley. They interrogate him with cold hostility that is as senseless as it is ruthless. The demeaning absurdity of it all disheartens the viewer. The two men go at Stanley until he screams with anguish. As with 1984, a reader marvels that such a play could achieve the popularity it has.

Starting on page 40, their interrogation of Stanley begins:

Goldberg: Webber, what were you doing yesterday?

Stanley: Yesterday?

Goldberg: And the day before. What did you do the day before that?

Stanley: What do you mean?

Goldberg: Why are you wasting everybody's time, Webber? Why are you getting on everybody's

wick? [to get on someone's nerves] Why are you driving that old lady off her conk? [to distract

someone severely]

McCann: He likes to do it!

Goldberg: Why do you behave so badly, Webber? Why do you force that old man out to play

chess?

Stanley: Me?

Goldberg: Why do you treat that young lady like a leper? She's not the leper, Webber!

Stanley: What the—

Goldberg: What did you wear last week, Webber? Where do you keep your suits?

McCann: Why did you leave the organisation?

Goldberg: What would your old mum say, Webber?

McCann: Why did you betray us?

Goldberg: You hurt me, Webber. You're playing a dirty game. . . . What does he think he is?

McCann: Who do you think you are?

Stanley: You're on the wrong horse.

Goldberg: When did you come to this place?

Stanley: Last year.

Goldberg: Where did you come from?

Stanley: Somewhere else.

Goldberg: Why did you come here?

Stanley: My feet hurt!

Goldberg: Why did you stay?

Stanley: I had a headache! . . . .

Goldberg: What can you see without your glasses?

Stanley: Anything.

Goldberg: Take off his glasses.

(McCann snatches Stanley's glasses. . . .)

Goldberg: Webber, you're a fake. . . .

Goldberg: Why did you never get married?

McCann: She was waiting at the porch.

Goldberg: You skedaddled from the wedding.

McCann: He left her in the lurch. . . .

Goldberg: What is your name, now?

Stanley: Joe Soap.

Goldberg: You stink of sin.

McCann: I can smell it. . . .

Goldberg: Where is your lechery leading you?

McCann: You'll pay for this! . . .

McCann: You contaminate womankind.

Goldberg: Why don't you pay the rent?

McCann: Mother defiler!

Goldberg: Why do you pick your nose?

McCann: I demand justice! . . .

Goldberg: You're a plague, Webber! You're an overthrow.

As dialogue, the effect creates a street-life collage of voices to depict an over-controlled, paranoid society. They pull poor Stanley apart and scrape his character to the bone. Goldberg and McCann do a deconstruction job on Stanley that employs elements of the absurd. The dialogue gives the play a zany, scary gloss that you won't forget easily. At the end of the play they lead the docile Stanley to a car, dressed in a "dark, well-cut suit," as the play's instructions dictate, and drive off into the night with him.

The viewer reacts to this scene as he reacts to Winston Smith. He laments the breaking down of the human spirit; but the process does have intentionality—to achieve correctness. The clothes Stanley wears should convey that.

The Fragility of Selfhood

What is the point of such horrible literature? Why should anyone read 1984 or The Birthday Party? I have read both works several times, and I agree with the negatively phrased questions—and reply that most readers probably should read something else. At the same time, they should see the books in the light of what historians and psychologists have known for eons, that people break more easily than we like to think. A term like "heroism" loses any relevance in 1984 and Birthday Party.

The British TV series from the 1960s, The Avengers, had one episode titled "The Fear Merchants."

It concerns an insanely ambitious industrialist who tries to take out all his competitors by driving them to nervous breakdowns. He employs a team of criminal psychologists who create a profile of the industrialist's rivals, pinpoint their psychological frailties, and exploit them. In one case, a rival has a fear of open spaces, so the psychologists' henchman drop him off at a huge soccer stadium in London and pipe in the noise of cheering crowds, leaving him terrified. The psychologists detect a phobic fear of spiders in a second rival, so the henchmen put spiders in his office, leaving him in a static, infantile state. In a more pedestrian setting, you would think of practical jokes gone wrong.

Every person has an achilles heel. A psychologist can profile him to find it, but his friends probably already know what it is. Nobody really needs violence to break a person.

The novel Walking Stick, published in 1967 by Winston Graham, makes this point. Nobody knows you better than the people around you. They can see the real "you" in your body language, in your personal choices, in conversation. Walking Stick appeared as a film in 1970 that starred Samantha Eggar and the late David Hemmings.

Hemmings plays an artist, Leigh, who courts Deborah, played by Eggar. She works for a firm that appraises antiques and holds auctions to sell them. Little by little, the reader learns that Leigh is not really in love with Deborah. He works for a gangster and gains Deborah's confidence in order to rob her employer.

The gangster learns from Leigh that Deborah cannot tolerate closed spaces. Since childhood, she has had a condition called claustrophobia; so he arranges a meeting in a loud, overcrowded bar to break down her will-power and make her assist in the robbery-plan. The same sort of ruse works in innocent, pedestrian situations as well, and of course as a practical joke. If people know you, they also know your weaknesses, and we all have a few. Only a nefarious person takes advantage of our weaknesses by manipulating them.

The Browbeating Culture

Intimidation occurs when the prevailing culture keeps casting suspicion on you. Press reports keep hinting at your perverse sexual proclivities—date-rapist, child molester, chronic sexual harrassment. The Nazis touched all these bases in the process of villifying Jews, leading up to the Holocaust and the World War. We like to think that everyone has learned the bitter lessons of the Nazi experience and will never practice Nazi methods again; but hey, why not? The Nazis, after all, only borrowed the methods that other people had already used.

The defeat of Nazi-Germany did not end tyranny, not by a long shot. Every dictator wants to rule a nation, a continent, or the entire world. He realizes that there are no polite ways to accomplish that.

Political parties understand the same principle. Nice guys finish last. If you want to win, you have to play dirty, ruthlessly and vindictively.

At the same time, using violence is so yesterday! There are better ways. Whisper-campaigns and unofficial hate-clubs, promoted in a hostile press, accomplish more than beatings or imprisonment can, and leave less collateral damage. Whisper-campaigns and hate-clubs blunt a person's natural resolve, undermine his personal philosophy, and cast suspicion on his political values. You learn to toe the line quick.

"But why?" you ask. "What's the point of putting people through all that, if we can more easily buy a car or book a vacation?" It happens because Mother Nature hard-wires conquest and acquisition into the human character. Don't ask me why, but is it the oldest profession on the planet—including even prostitution. And people latch on quickly to a moral imperative, no matter how much it affects their personal comfort-level, or their daily routines.

Defining religion in its loosest sense, religion is as religion does. It consists mostly of carrying a set of beliefs to the conquered enemy and forcing them to accept those beliefs as their own. People get a thrill and feeling of self-empowerment by forcing their will on others, whether the work involves religious practices, a prevailing philosphy, a political system, or cultural norms. Truth takes second place, even under the best of circumstances, to the will of the victor. Tolerance and diversity are just words, open to a lot of interpretations, but usually involve practices dictated by the victor onto defeated persons. We must not forget that it is just another form of conquest.

America's conflicting moral imperatives are wrecking the country. What we should look for, in the rhetoric of the opposing sides, is not live and let live, but "Live the way I tell you!" The only way to save the country now is to divide it. We can live and let live only within our own dominions.