Lawn-chair Larry

During the Summer of 1982, I lived with two other guys who graduated from Furman after I did. We did not keep a TV in the house, and didn't subscribe to any newspapers, so we missed the story about a man named Larry Walters, who tied 40 weather-balloons to a lawn-chair, hung jugs of water from it for ballast, turned himself loose, and sailed into the stratosphere. The lawn-chair didn't even have a seat-belt.

I first read about Lawn-chair Larry in Susan Pinker's 2008 book Sexual Paradox. Pinker writes that Larry had dreamed about flying since childhood. He hoped to tour his California neighborhood and the surrounding area—"float up to about thirty feet above his backyard, fly around up there while enjoying the view . . . then shoot a few of the balloons with his pellet gun . . . so that he could float back down."

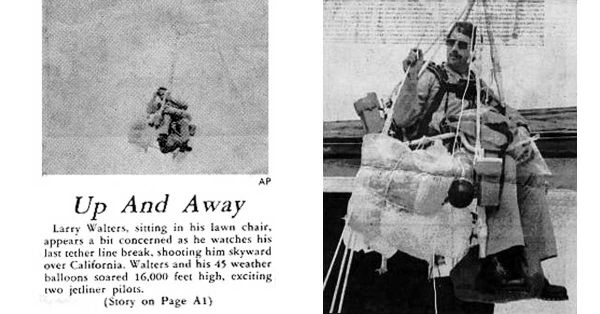

Instead, Larry "streaked into the L.A. sky as if shot from a cannon, pulled by the lift of forty-five helium balloons. . . . He did not level off at a hundred feet, nor . . . at a thousand feet. After climbing and climbing, he leveled off at sixteen thousand feet. At that height, he felt he couldn't risk shooting any of the balloons, lest he unbalance the load. . . . so he stayed there, drifting with his beer and sandwiches for several hours." Press-reports said the temperature at 16,000 feet was 2 °F, and that he began to get altitude sickness and frostbite.

Then he veered into restricted air-space—the Los Angeles Airport. Airline pilots radioed that they had seen a guy in a lawn-chair at 16,000 feet. Larry eventually shot out some of the balloons and drifted back down. Unfortunately, he veered onto a power-line, knocked it out, and blacked out a neighborhood of Long Beach.

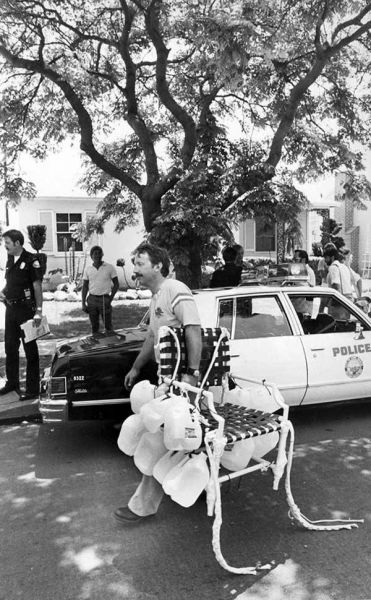

Upon landing, news-reports said, Larry "was swarmed by excited children from the neighborhood. Everyone came out to see what the commotion was about." He even signed a few autographs on the helium balloons. Pinker concludes the story saying that when a news reporter asked him why he had done it, "Larry answered nonchalantly, 'A man can't just sit around.'"

Walters's stunt "earned him plenty of ridicule," and he must have flinched at the $1500 fine he had to pay for violating restricted air-space, and although he appeared on talk-shows . . .

Larry Walters on the David Letterman Show

the poor guy was never able to restart his life and ended up killing himself ten years later.

If only Walters had known that his famous lawn-chair, named Inspiration-1, would later turn up in the Smithsonian's Air and Space Museum. If only he had known that he had awakened such a need in other people to go airborne, that at least a dozen people imitated his feat in the coming years. If only he had recognized how much he had struck a chord in people, giving them courage to pursue their dreams, and ignore the naysayers.

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Lawn-chair Larry did not lack admirers. Wikipedia lists Larry's imitators. It reads like a Who's Who of copycat daredevils:

- New Year's Day, 1984: Kevin Walsh lifts off from Stow, Massachusetts, powered by 57 helium balloons.

- Mike Howard and Steve Davis lift off from Los Lunas, New Mexico in 2001, powered by 400 balloons, to reach 18,300 feet—enough to break Larry Walters 16,000 foot record.

- In 1992, Yoshikazu Suzuki lifts off from Lake Biwa in Japan powered by 23 helium balloons.A Japanese Coast Guard plane spots him 480 miles off the coast of Japan, but he is never seen again.

- In 2007, Kent Couch, a 47-year-old gas-station owner lifts off from his home in Oregon with 105 balloons tied to his lawn-chair. He remains aloft for 9 hours and travels 240 miles.

Wikipedia lists no less than eleven copycats—among them a man who wanted to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Another successfully crossed the English Channel. All are males. The 2009 Pixar-movie Up deals with a man who floats his entire house.

Males being what they are, I suspect that any dramatic change in the society will have to come from them. Women don't have the gift (or curse) of outlier thinking, which was the basic point that Susan Pinker tried to make in Sexual Paradox.