Leadership is a Given

Leadership basically means that you take responsibility for the actions and the results of something. At the end of the day, you stand under the gun for all that happens. You get either heaps of praise or all the blame. Sometimes, you only have to take responsibility for your own actions. Sometimes, other people expect you to take responsibility for their actions;—or you bail out of any sense of responsibility and let a third party take the blame and assume leadership.

Either way, leadership is a given, whether you assert responsibility for yourself and others, or when you reject responsibility. At some level, it remains your choice. In the Book of Exodus, Moses took responsibility for the Israelites, when the Lord commanded him to do so. At first, they went gladly with him, to get out of their enslaved state in Egypt. Later, however, as the Israelites crossed endless wilderness on their way to the Promised Land, they lashed out at Moses for taking them from their orderly, predictable life in Egypt. Never mind that they lived in slavery, their lives had structure and order, and someone was in charge all the time.

In The Brothers Karamazov, Ivan Karamazov tells the story of the Grand Inquisator who presides over the Inquisition in Medieval Spain. The Lord appears to him. Without saying a word, the Lord accuses him of denying freedom to the people he persecutes. The Inquisitor retorts angrily, "Didst Thou not often say 'I will make you free'? But now Thou hast seen these 'free' men. . . . Yes, we've paid dearly for it."

Yes, in the core of our souls, we make the decisions. Passively or pro-actively, directionally, or in retreat, we make them all. At the center lies our sphere of responsibility. When the Lord appears to us in that sphere, we tell Him we have little use for His freedom, that freedom has little practical value in the Real World. His mute reply will be that we do exercise our free will, for what it's worth. We lead ourselves, even if we hate every minute of it—hate taking the incumbent risks that test our sense of judgment.

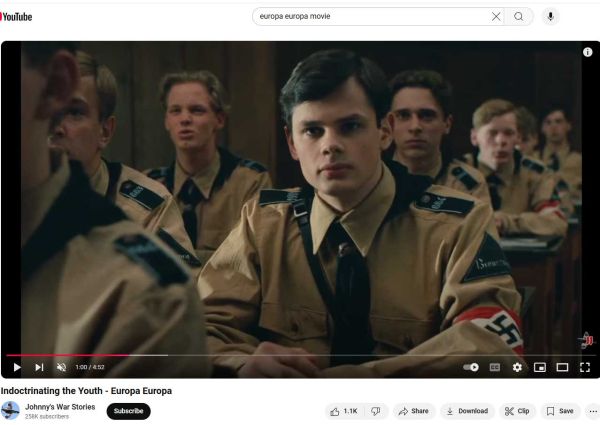

The Nazis understood that the way to subdue people is to organize them. Every German during the Nazi-era belonged to an organization—and most of them to several organizations. Keep them busy! Take up their time with meetings, marches, and so on. They were not just Germans and Nazis, they also belonged to the Hitler Youth, the Bund of German Girls, and the Workers' Front. They sported membership pins and should-patches. They gained a sense of pride in belonging! It was as much as they wanted—anything to defeat the existential angst of not belonging!

But the organization has a double-edged sword. If you belong to it, it controls you. If you abdicate your responsibility for yourself, you let others lead you; and an organization relies on human nature to guide it: It secures the loyalty of its members. It encourages attendance of indoctrination courses and conferences. It puts dissent on a tricky footing: Oppose the party-line and face an accusation of disloyalty and the risk of expulsion.

Eric Hoffer writes about the insecurity and paranoia of members. They know they have abdicated a sense of responsibility for themselves—abdicated their personal freedom for an illusive sense of security and belonging. It makes them peevish and suspicious. They say to each other, "Let's stick together!" so their "Second-Class" shoulder-patches won't stand out. They surrendered self-respect and ego-strength, and they can't win those qualities back, except by going it alone.