Life is Personal

LIFE IS PERSONAL

I remember well the old Simon and Garfunkel song "Mrs. Robinson," which Paul Simon wrote for the movie The Graduate, directed by Mike Nichols. He and Garfunkel also included the song on their 1968 album Bookends. Simon changed the name of his song from "Mrs. Roosevelt" to "Mrs. Robinson" to fit the name of the movie's main character, played by Anne Bancroft. The third stanza of the song deals with bourgeois futility and ennui:

Sitting on a sofa on a Sunday afternoon,

Going to the candidates' debate,

Laugh about it, shout about it,

When you've got to choose,

Every way you look at it, you lose.

The song reminds me of social gatherings I have attended, where the guests argue issues with a harmless bourgeois futility, and no one gets hurt. They bring along a check-list of political and cultural talking-points, or else shoot some innocuous everyday breeze—their politics, the World Series, whether Trump is the worst President, or Biden. It just sounds like a masquerade. Who are these people behind the masks, and what do they really care about? The farther we live from the centre of things, the more we can flaunt the masks, the less connection we have to real things.

You can wreck a nice social gathering, if you get the right people going on a controversial subject. In my parents' generation, defined by the Great Depression, World War II, and the lingering threats posed by the Cold War, you could touch off a row by bringing up the Alger Hiss Case. Guests would start looking for their coats and hatss. In Paris, in the late nineteenth-century, party-givers sent out invitations, promising that no one would discuss the Alfred Dreyfuss Case, which, like the Hiss Case, involved espionage and treason. No one wants to attend a party, if they have to listen to battling parade horses.

In modern-America, party-givers might decide not to allow anyone to mention abortion. Not even the Trump-Biden rivalry can match the strife that abortion can cause; so tell them to shut up about it, or take it outside. Besides, politics is a mask. Life is personal.

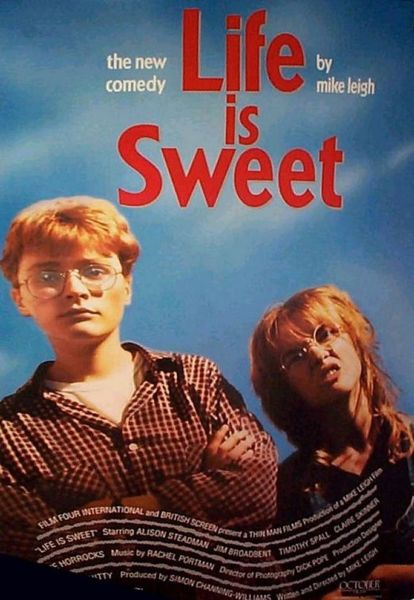

Before people start debating whether "Women's Rights" should take precedence over "the Rights of the Unborn," they should watch a British movie from 1993, titled Life is Sweet, directed by Mike Leigh. If you attend a party, you may not want to talk about abortion, but you could talk about Life is Sweet, which deals obliquely with it.

The movie deals with a middle-class family struggling to make ends meet and create some happiness for themselves and each other.

Life may or may not be sweet, but we live it on a personal plain. It may not turn out sweet, even with a healthy psyche governs and a sense of personal continuity. Our yesterdays guide our tomorrows. People interact and influence each other.

Personal experiences influence us, and we tell others, and they relay their comments back to us. A lot of that kind of stuff goes on in the lives of average people.

In Life is Sweet, Nicola behaves like a lot of highly-intelligent, over-sensitive, dysfunctional girls.

She smokes and drinks, and is sexually mature, but in conversations with her mother, she looks like a disgruntled, grieving little girl, with a querulous, nasally voice. Nicola doesn't need an abortion. She only wishes that her mother had had one, instead of giving birth to her, so that her messy life would never have happened.

Nicola's mom tells her she became pregnant when just a teenager and married her eighteen-year-old boyfriend, who had only just started training in the hospitality industry. He had to give it up and go to work. She delivered twins during a difficult beginning with her new husband. Nicola just could not tolerate the thought that her birth wrecked her parents' chance to create a stable environment for their marriage, to get an education and to make plans for the future. Nicola has little sense of self-worth anyway. It makes a poignant scene.

Her mom tells her she could not bring herself to abort her children. She were not simply blobs of protoplasm but "two little lives."

The movie does a good job of expressing a root problem for Whites, that we like to plan things and for everything to be perfect. We do not react well to unwelcome surprises and for things to end in a muddle. We'd rather scrap our plans and start over, or else not invest in plans, rather than having to spend a lot of time fixing a snafu.