Loyalty to Whom, to What?

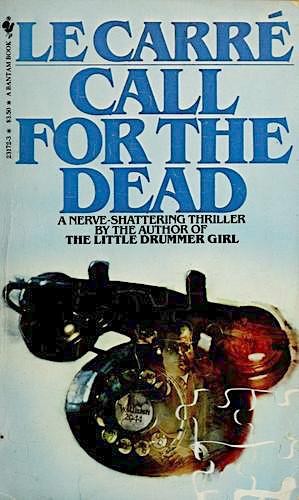

I watched The Deadly Affair movie in 1967 on my family's little kitchen TV, when I was 14 years old. Years went by, and I had mostly forgotten it. I didn't remember its title, the actors' names, nor most of the plot; but enough fragments of it hung on in my memory-bank—so that when I started reading John le Carré's novels in 1980 (after watching the Tinker, Tailor mini-series on the TV), I recognized the movie right away as The Deadly Affair, the film-version of le Carré's first novel, Call for the Dead, published in 1961.

I don't like having to use "spoiler-alerts", like "Don't tell the children Santa Claus is really Mommy and Daddy", or "Don't tell me who won the Battle of Midway until I see the movie." I say, find out who won the Battle of Midway and watch the movie anyway. Learning who won Midway is just a fact. Watching the movie is a tension-filled human-drama, with surprisingly good acting from both

Japanese and American actors. One American pilot has a Japanese-American girlfriend who waits for him to return home, each day.

The plot of Call for the Dead deals with several historical issues: London during the Cold-War era of 1960; three characters who are German Jews; two of whom had sought refuge from Nazism in England. All three had been members of the Communist Party, in Britain or in Germany. Two of them had spent time during the War as inmates in Concentration Camps.

The novel begins with the apparent suicide of Samuel Fennan, employed in Britain's Foreign Office. Someone had sent a letter anonymously to Fennan's superior, accusing him of earlier Communist Party membership. Le Carré's spy-hunter George Smiley interviewed Fennan about his membership and decided that Fennan no longer had ties to the Party.

But the proximity of the two events brings a lot of official heat on Smiley. On top of that, he has to interview Fennan's widow Elsa to learn more about her husband's death. Elsa tells Smiley that his interview with her husband left him despondent and pessimistic about the future. He actually typed the suicide letter to his superior, complaining that he is the "victim of paid informers".

But Smiley learns that Fennan had asked for a wake-up call for the morning after his death. Smiley also receives a letter from Fennan after his death, asking Smiley to meet him that day. Fennan had even taken the day off from his work at the Foreign Office, something he rarely did, and apparently did not tell his wife. So Smiley begins to suspect that Fennan did not die by his own hand, but who could have killed him, and why?

Elsa Fennan immediately falls under suspicion; but before Smiley can go any further, his superiors in the Secret Service call him off the case. Their interference in the investigation infuriates Smiley, and he resigns. He writes a letter of resignation to his superiors and leaves Fennan's letter asking to meet him pinned to the resignation. Luckily, he connects with Mendel, a Special Branch officer, and the two men continue the investigation unofficially.

Mendel learns that Elsa Fennan meets with a handsome, blond-haired foreigner at a London theatre every two weeks, and that they exchange brief-cases. But before Smiley can do anything with this information, the blond-haired foreigner nearly kills him. Fortunately, a Secret-Service colleage of Smiley's identifies the foreigner as Hans-Dieter Mundt, an East-German Stasi officer. He flees the country before Smiley can interview him.

The quality of the characterizations in Call for the Dead, the historical backdrop of the novel, and the expertly woven plot put it head-and-shoulders above most other fiction of the genre. On top of that, Le Carré never gives a reader pat, predictble endings, and he leaves readers with questions that will remain in their heads for a while longer:

- "You are the man who interviewed my husband," Elsa said, "about loyalty."

Smiley felt suddenly sick and cheap. Loyalty to whom, to what? - "I liked your husband very much. He would have been cleared. . . ."

"You said you liked him. You didn't give him that impression apparently." - "Why did she do it?" Mendeal asked suddenly.

"I think she dreamed of a world without conflict, ordered and preserved by the new

doctrine. . . . I think she looked at the futility of her suffereing and prosperity of her

persecutors and rebelled.

"Was she a communist?"

"I don't think she liked labels. I think she wanted to help build one society which could

live without conflict. Peace is a dirty word now, isn't it?"