My Thoughts on One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

Learning How to Live Free

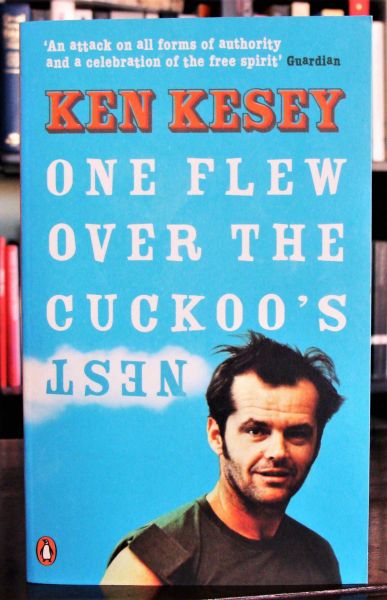

Jack Nicholson as Patrick McMurphy from the movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

When One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest appeared on the TV for the first time, some years after it had finished up in movie theatres, I watched it for perhaps ten minutes, then switched it off. I had read the novel that it was based on and knew the whole story by heart. I could picture scenes from it in my mind—like live-action dramas. I could hear, so to speak, the characters' voices. It is a very good book about an unpleasant subject.

Something about the movie did not feel right to me. Maybe my imagination had used the input from the novel to fix the characters in my mind, and make the characters as real as real-life. The movie-characters did not do as good a job. They could not hold a candle to the "real" characters.

While Ken Kesey published his novel in 1962, the movie did not come out until '75, starring Jack Nicholson as the mental patient Patrick McMurphy and Louise Fletcher as Head Nurse Ratched. Maybe Nicholson did not look enough like a gang-biker, and did not have McMurphy's requisite red hair; or maybe Fletcher's Southern accent did not fit the Pacific-Northwest locale.

One Flew remains one of my favorite works. Ken Kesey also appears as a character in The Electric Kool-aid Acid Test, by Tom Wolfe, published in 1968; but whereas Wolfe continued to publish until his death in 2018, Kesey published little after One Flew, until his death in 2001. Disappointed readers could not understand it. He was not just a writer. He had an insider's view of the '60s Counterculture. Perhaps Kesey preferred to live out his novels, rather than write them.

Take note of the above-photo and read the publicity-blurb provided by the Guardian, a British newspaper. The blurb describes One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest as "an attack on all forms of authority and a celebration of the free spirit." I believe the blurb oversimplifies and even misrepresents the intentions of One Flew, but so what? It has lured thousands of readers with a catchy anti-establishment line.

Stacked alongside hundreds of other books in a bookstore, One Flew could hold the attention of a customer for perhaps ten seconds. He may glance at the blurb for just a second or two. A book really has that long to persuade a reader to make a purchase, before he wants to move on to other books. Publishers use blurbs to attract readers and sell books, not to make definitive statements about them.

Truthfully, I read One Flew because a literature professor made it part of the syllabus for a college course, The Modern American novel, during college. Some of my classmates admitted to me that they could not see the point of One Flew and hated it. Maybe they expected it to have an anti-authoritarian plot and were disappointed.

Even readers who finish One Flew may conclude that the dictatorial, abusive asylum, led by the authoritarian Nurse Ratched, represents all that is oppressive about human society. ("Well, that's what the Guardian said about it.") Plenty of other media-outlets echoed that view. Time magazine, for example, writes that "Kesey has made his book a roar of protest against middlebrow society's Rules."

Louise Fletcher as Nurse Ratched

When our class actually started reading One Flew, prompted by the media blurbs, we accepted it as a "fight-the-power" kind of story: McMurphy our hero, Nurse Ratched the emotionless, rule-laden drudge, and Chief Broom, the mute observer who narrates the story. We ran into a few problems. They emerged just gradually as McMurphy settled into the routines of the asylum.

The other inmates complain bitterly about the Nurse's inflexibility, her adherence to rules—regarding the use of the TV set, for instance, and cigarette-smoking—and her overall heartlessness. They also hate that the Nurse never lets them out of that place. It's not a prison, after all. They should interact with the outside world, if they hope to ever return to it.

Life at the asylum is a monotonous regimen of prescription drugs, physical therapies, and lengthy, disparaging talk-sessions that leave the patients demoralized and timid. The nurses and orderlies keep them herded together, ostensibly to keep them out of trouble, but they lack time alone and to develop selfhood and initiative apart from the others.

A rebel at heart, McMurphy takes up the cause of the other patients. To his surprise, they make him their de facto leader. But he soon realizes he has taken on more than he can chew. The Nurse can use her own discretion about keeping him incarcerated, for as long as she deems it necessary. McMurphy tells them he would love to leave the asylum, but can't! He won himself a transfer from prison to the asylum. In either case, he cannot leave. The police would hunt him down, bring him back, and add to his incarceration time.

And if that isn't bad enough, the other patients convey another fact that worries him even more. They sort of pull the rug out from under him. What McMurpy realizes about them is so important, I include it here in a paraphrased form:

"You know what I'm talking about, Harding. Why didn't you tell me she could keep me committed till she's good and ready to turn me loose?"

"Why, I had forgotten, you're committed." Harding's face folded in the middle.

"I got just as much to lose hassling that old buzzard as you do," McMurphy said.

"You have more to lose than I do," Harding says. "I'm voluntary. I'm not committed. As a matter of fact, there are only a few men on the ward who

are committed." Harding's rearing smile fades and he goes to fidgeting around, from McMurphy staring him so funny. He doesn't say a word. He's got that same puzzled look on his face.

"Are you bullshitting me?"

Nobody says anything. McMurphy walks up and down in front. "Tell me why?

You gripe, you bitch for weeks on end about how you can't stand this place,

can't stand the Nurse or anything about her, and you ain't committed?"

Then he says, "Hells bells," in a weak sort of way. "I don't seem able to get it

straight in my mind."

The guys don't agree with McMurphy. They say they know what the trouble is.

McMurphy interrupts them. "All I hear is gripe, gripe, gripe. About the nurse,

the staff, or the hospital. Sefelt blames the drugs. Fredrickson blames his

family trouble. Well, you're all just passing the buck."

This passage in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest defines it for me. It tells the story of a group of losers learning to love freedom and to take risks again. They have short-changed themselves for years by abdicating responsibility for themselves, and now McMurphy challenges them to regain self-respect and courage and get the hell out of there!

They have lived in the asylum for so long, they can no longer provide for themselves. It is easier to let Nurse Ratched and her staff provide for their wants. They have too much pride, of course, to admit that much to themselves. They focus all their rage on the Nurse, and treat her as if she has deprived them of their freedom—pass the buck, as McMurphy says, rather than risk blaming themselves.

But McMurphy continues to take their side against the Nurse. In a sense, neither side wins the war against authority. Drunk and angry at the Nurse, he strangles her, nearly choking her to death, before the doctors and orderlies subdue him. They haul him to surgery and perform a Lobotomy on him, which kills the soul of McMurphy—neuters him.

But before they can subdue him, he manages to rip open the front of Nurse Ratched's uniform. The other patients and the oderlies can hardly believe what they see: "(T)he two nippled circles started from her chest and swelled out and out . . . warm and pink in the light."

I interpret her starched white uniform as sexual repression, like Lady MacBeth in the Shakespeare play MacBeth. She prays "Unsex me here!" as she and her husband plan the murder of King Duncan. Prayers may work for Lady MacBeth. They probably would not work as well for Nurse Ratched.

Bureaucratic Drudgery

If I had to choose between battling Army Ants in South America or tending to senile, incontinent old people in end-station institutions, I might still choose the institution. Neither choice appeals to me much. Army Ants are terrible creatures. A short-story by the German author Carl Stephenson, "Leiningen Versus the Ants," published in 1938, describes in graphic terms Army Ants stripping the carcass of a deer.

If I had to choose between cleaning a toxic-waste dump and battling psychotics and paranoiacs in an asylum, I have to admit, I don't know which I would choose; but the idea of doing either institutional job—dealing with the smells of human-waste and lunatic old people—would itself resemble a toxic-waste dump. I can see myself grow tougher and crueler as a necessary step, to just doing my job.

Here is my problem. At age 69, I have experienced a young man's anti-establishment POV, the literature major's curiosity at human behavior, and the view of an older man with a long, varied work-history. These points-of-view cannot abide each other on the same page. So I don't have easy answers. All I can do is inform.

But even as a college student, I did not believe that the anti-establishment stance held much water. Half-way houses, convalescent homes, psychiatric hospitals—there are simply not enough of them to hold all the people who want to get in them. To make matters worse, the institutions have to manage nagging budgetary issues. As I asked before, who wants to work in a place crammed full of crazy people?

An institution has to find its competent people anyway it can—who are often Nurse Ratched types—punctillious bureaucrats with no personal life. If it wants thoughtful, humane supervisors, it has to pay them more; so the institution takes less competent people out of financial necessity.

In one scene of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Kesey writes about the interior of Nurse Ratched's office, where she displays a commendation from the governor of the state, who congratulates her for her management skills—for pulling an administrative rabbit from a low-budget hat.

Finally, I should add a word about cuckoos. They are a species of bird that lives in the forest and makes a distinctive "cuckoo!" call. They don't build nests but lay their eggs in the nests of other birds, rather like many humans. On that basis, I recommend that the Kesey estate change the title of his novel to No Wonder Cuckoos Don't Have a Nest. They someone else take care of it.