Participatory Democracy

During college, I took the introductory political science course from an instructor whose specialization was urban planning. During one class-session, he tried to explain to us the concept of "participatory democracy." I am sure I yawned a lot during his class, as I did during much of my college education, because I had so little sense of career-orientation. The instructor, as urban-planner, considered participatory democracy a good concept, as the means to expedite solutions to urban problems. I consulted the Wikipedia article on "Participatory Democracy," which is also mostly favorable.

Much of what I studied in college went in one ear and seemed to go out the other; but in the years since, I realize that I had actually retained a lot of it--participatory democracy, among many other things, subject to my more critical thought-process. On the one hand, every citizen participates in a democracy when he votes, so "participatory" appears to be redundant. On the other hand, the working-level definition of the term really refers to direct government--participation in policy-making by individuals or constituencies who work side-deals with the government for special consideration of their needs. Not really democratic at all, in other words.

Wikipedia's article contains mostly perfunctory or miasmic criticisms, suggesting a less than knowledgeable reaction to the idea, that overlooks an important reservation, that participatory democracy leads to striving among the participants for greater influence. It pits participant against participant, constituency against constituency. I have actually seen this problem at work. Each participant tries to communicate grief and despair more convincingly than the others, for greater favor. Some of the participants hint that the officials better not let them down. Participatory democracy reminds me of government-grant applications, but more shrill and combative.

More seriously, participatory democracy subverts the functioning of a freedom-loving society, inasmuch as the citizenry looks to the government for solutions. The manipulation of officials reveals the public's abject dependence on them. This abject dependence gives the government a greater sense of prerogatives in dealing with the problems and a greater sense of justification for the measures it employs to resolve them. The mood of the public transitions into a deterministic kind of restiveness.

An article in last Sunday's edition of the Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper deals with the participatory-democracy issue with surprising directness. The title of the article, "Alle sind Schuld an der Bürokratie," or in English "Everyone is to blame for the bureaucracy being what it is." The under-title reads, "The bureaucracy would not be so burdensome, if people did not place such high demands on it." The italicized text highlighted in the second column reads "Citizen constituencies demand new laws that address their particular concerns."

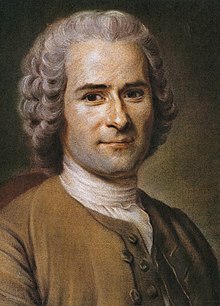

The Wikipedia article on participatory democracy cites a number of influential people. Not surprisingly, they are all leftists. Jean-Jacques Rousseau wanted to "enhance equality" and "shape the common good." Carole Pateman, "a feminist and political theorist" is a "critic of liberal democracy." G. D. H. Cole "believed in common ownership of the means of production." Cole "belonged to the Fabian Society," which pushed "radicalism, a left-wing tradition." Cole nevertheless died a millionaire! Participate in democracy for profit, you might say.

Of course, Republicans do not want lots of people working for the government, as it causes a rivalry with private businesses and private employees. Regardless of how it affects society as a whole, government workers are not likely to accept anything that negatively impacts their jobs, their departments, and their scope of responsibilities. They will support steps that favor their security, political power, and influence. The private orientation of the society works against their best interests, so they will oppose it.

There is no reason why our nation could not allow both political theories, the private-orientation society in one new country, the common-ownership concept in the other. It is a no-brainer, except for Americans' fear of change; but if it does happen, everyone will flee the common-ownership concept, because it has been tried numerous times with disastrous results. It cannot maintain the level of prosperity that a private society ues Rouseau has already established. The common-ownership model would stick out like a sore-thumb.