Re-examining The Little Drummer Girl

Re-examining The Little Drummer Girl, by John le Carré

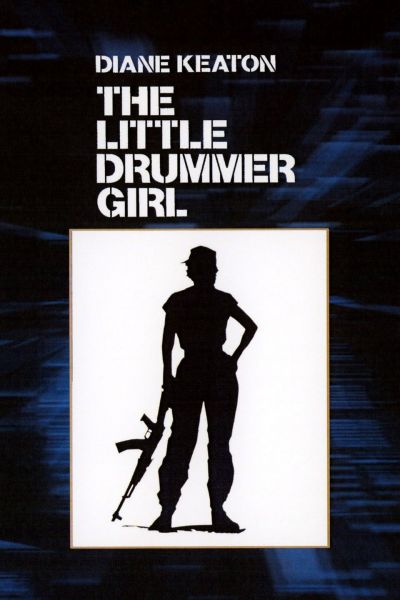

Movie poster for The Little Drummer Girl, 1984, starring Diane Keaton

The American novelist John Grisham has said that he reads John le Carré's The Little Drummer Girl every year or two to revitalize his own writing. I am sure that most writers have a favorite older writer they turn to for inspiration. That a successful writer like Grisham reads le Carré should serve notice to the reading-public that le Carré the craftsman is pretty good. He has a gift for inventing intelligent, believable stories and sets each scene with precise descriptions that don't stretch on for pages. Even second-tier characters have definition. They have a charming quirkiness, until someone threatens them, and they show their steel or bad intent.

The culture rates a writer by the number of books he sells, how many reviews he gets on his Amazon page, or how often he appears in People magazine. Writer don't just write; they also sell their writer's persona in as many speaking engagements and interviews as they can tolerate. It's all part of Entrepreneurship 101 for writers. One writer described the profession as "a contact-sport." The hurdles of a writer are many, and the writer who gets over them deserve his heaping rewards.

John le Carré started "le Carré Productions" for unknown reasons. When I mentioned this to a friend, he yawned. "Oh, yeah, everybody's got a production company;" but I am not sure what a "production company" does. Does it come equipped with a studio, sound-mixer, and camera set-up, various technicians? You learn the ropes as you go along, I guess.

The quality of le Carré's writing fell off precipitously after A Perfect Spy. The latter books retain little of the style and substance that distinguishes le Carré from other writers. Perhaps his "production company" employed ghost writers to maintain his output of books, so he could retire. Maybe it will stay in business, now that he has passed on.

You don't achieve le Carré's level of success and forthrightness without some serious pushback, The Little Drummer Girl being a case in point. Like a lot of books, it came in for flack from tolerance/diversity advocates, for its take on Palestinian issues and for its demeaning portrayal of the main character, a young woman named "Charlie" (short for "Charmian"). Some readers cannot bear books that clash with the cultural trends, and simply won't read them.

Drummer Girl has had two film adaptations to help it appeal to a wider audience—in 1984 with Diane Keaton and in 2018 with Florence Pugh. Neither has the character and complexity of the character Charlie. They just tell a middle-brow spy-story, which are really a dime-a-dozen, when you come right down to it. If I had to cast Charlie, I would look at someone like Julianne Moore, who has Charlie's assertive, left-wing temperament and red hair.

Julianne Moore holds both British and American citizenship

One reviewer has written that, to say le Carré's novels are about spies is like saying that Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment is about crime. Most people only think in generic terms; but if you know anything about le Carré and try to pass him off as a "spy-novelist," I hope you cringe with shame, unless you recognize how much he surpasses the genre.

Educated people feel like beggars in the snow when we deal with the billion-dollar film industry. We don't get the sustenance we need from dumbed-down, politically-correct feature-films. The press may call us "Snobs!" "Elitists!" Shit, we're starving for something good!

The Little Drummer Girl is not About Drums

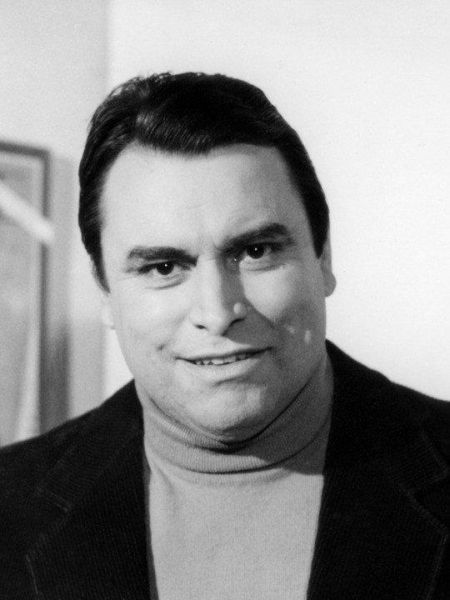

Drummer Girl really gives a reader two stories for the price of one. As they unfold, they also start to merge. The main character of the first part is an Israeli named Marty Kurtz, a counter-terrorism specialist. If I had to cast Marty, I would reach back in time and select the British actor Brian Blessed, now 84-years-old. He is big and hard, but with a paternal quality. His performance in the BBC's mini-series I, Claudius from 1977 stood out.

Actor Brian Blessed

The focus on Marty continues until Chapter Three, then switches to Charlie, the main character in the second part of Drummer Girl, a down-at-heels British actress. Le Carré never reveals her last name, accentuating her anonymity. That doesn't mean that a reader does not know her. After all, he accompanies her through the story, walking by her side for miles.

The two parts don't come together until Chapter Six. Marty's meeting Charlie seems an unlikely event. She is fiercely left-wing and pro-Palestinian, and curses Marty and the other Israelis, threatening them with physical violence. But Marty has an ace up his sleeve. He knows that Charlie is an actress and needs work. He offers her a role in the "Theatre of the Real."

But first, Marty has to prep Charlie for her role. To accomplish that, he and his crew basically deconstruct her. They have studied her life up close and catch her each time she tries to embellish or conceal. The book is uncomfortable to read. The Israelis strip Charlie down, scrape her raw, all in the name of giving her a professional make-over.

She has to confront the tawdriness of her life. Her demeaning failure to amount to anything personally or professionally comes back to haunt her. She has slept around with so many guys, she no longer understands the needs of a real relationship. She has played so many roles, she has the intellectual stability of a rag-doll.

The Israelis push Charlie close to a dark void, and she must face the fact that she no longer knows herself. The Israelis call it her "audition," and it just goes on and on—lasting all night, over forty pages of Drummer Girl. It is harrowing to read—like a torture session. The reader will hate how the Israelis carelessly scrape Charlie to the bone.

Kurtz is assisted by "Joseph," aka Gadi Becker. I would cast the American actor Steve Guttenberg to play Joseph. Guttenberg has mostly done comedy. Only occasionally has anyone tried to cast him as a heavy.

American actor Steve Guttenberg

On 29 March 2021, I uploaded a post titled "Intimidation." In it, I explore examples in literature where men with personal authority break down lesser men by browbeating them into submission. Kurtz and his staff do something similar to Charlie. It is another demonstration of the fragility of selfhood.

This sort of treatment of actors is not uncommon. Andy Griffith, who played the lead role in Elia Kazan's movie A Face in the Crowd, told Kazan's staff, "You s.o.b.s are never going to do this to me again!" They turned the amiable hayseed Griffith into a loudmouthed, alcoholic sociopath—totally believable, acting against type. He has a haunted, conflicted edge that taints his overblown joviality.

Actor Andy Griffith with co-star Patricia Neal

Kurtz and his staff interrogate Charlie, taunt her over her evasive answers, and pull away one pretense after another. In reality, she is only a pretender, an actress with no beliefs. She engages in role-playing, off the stage as well as on it. Again and again, Kurtz questions her about the basis for her left-wing stance:

-1. "You oppose technology gone mad," he continued equably. "Well, Huxley did

that for you already. You aim to release human motives that are, for once, neither

competitive nor aggressive. But in order to do this, you have first to remove

exploitation. But how?"

Stop patronising me, will you, Mart? Just stop!"

-2. "The pursuit of property is evil," said Kurtz. "Ergo property itself is evil, ergo

those who protect property are evil. Since you avowedly have no patience with

the evolutionary democratic process—blow up property and murder the rich. You

go along with that, Charlie?"

"Don't be bloody silly! I'm not into that stuff!"

"You mean you decline to dispossess the robber state, Charlie? What's the matter?

Shy, suddenly?"

"'The state is tyrannous'," Litvak put in helpfully. "Charlie's words exactly."

"I don't want to blow anything up! I want peace! I want people to be free!"

But Kurtz seemed not to hear her: "You disappoint me, Charlie. All of a sudden,

you lack consistency. . . . You' telling me you're recanting on your stated position,

Charlie?"

"I haven't got a stated position!"

-3. "Charlie, you mentioned in passing a while back that you and Al attended a

certain residential forum down in Dorset some place," said Kurtz. "A weekend

course in radical thinking. . . .

"Seems quite a place," he remarked genially as he read the press clipping.

"Weapon training with dummy guns. The techniques of sabotage. . . ."

Charlie tries to explain that she doesn't really have anything against Israel or the Jews:

"It's all right for you, you're a Jew. . . . You've got these fantastic traditions, the

security. Even when you're persecuted, you know who you are and why. But for

us—rich English suburban kids from Nowheresville. . . ."

Like Andy Griffith in A Face in the Crowd, Charlie has to act against type—from a superficial, left-wing loudmouth to a left-wing decoy. They leave her left-wing views intact; but she works for them now and does what they tell her.

It is a curious irony—an actress playing a role, behaving falsely, if you will—to play the role of her life in the "Theatre of the Real," involving real danger, with real guns and bullets, real blood, and real deaths. She will lead them to a Palestinian terrorist, even as she maintains outwardly sympathetic viewpoints.

The British double-agent Kim Philby wrote in his autobiography that spying is a kind of controlled schizophrenia. Philby admired John le Carré and wanted to meet him in person when le Carré visited Moscow, where Philby had lived since his defection in 1963; but le Carré refused. He held Philby in open contempt for betraying his country: "I still think he's a shit," le Carré said.