Reason as Logic? Or Reason as Motive?

REASON AS LOGIC; REASON AS MOTIVE

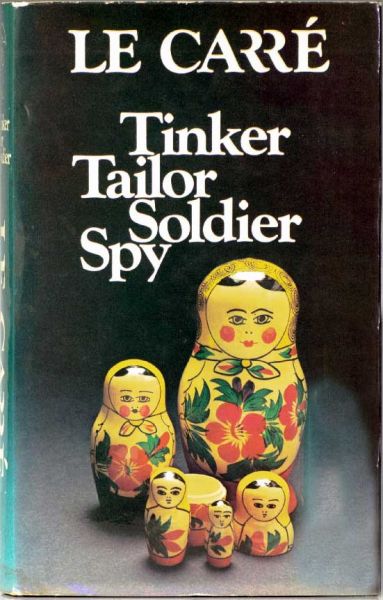

The late John le Carré published perhaps his greatest spy-novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy in 1974. In Chapter 11, the elderly spy-hunter George Smiley announces to his friend Peter Guillam that he has been "sacked," or forcibly retired. Smiley and Guillam visit a pub in Wardour Street, then go to a wine-bar near the Charing Crosss Road. Guillam asks, "Did they give you a reason?"

Smiley fixes on the word "reason," and replies with erudite drunkeness: "Reason as logic, or reason as motive?" Then he adds, "Or reason as a way of life?" With some bitterness, he continues, "They don't have to give me reasons. I can write my own damn reasons . . . and that is not the same as the half-baked tolerance that comes from no longer caring."

Maybe we all need to get drunk more often, and bring along a friend to whom we can deliver such wisdom. If I had to choose between "reason-as-logic" or "reason-as-motive," I think I would select "motive." Reason-as-logic permits a tendentious cast to one's thought-process; so stick with motives to define your choices, rather than logic. Leave the reason-as-logic thing to the doctrinaire types. If you want to induce apathy in people—i.e. "half-baked tolerance"—you can't go wrong if you call it "logic."

Keep "logic" under a jaundiced eye. People who define things with logic perform differently from those who stick with reason based on motive. To use an example, citizens in former East Germany had to listen to the Marxist reason-as-logic thing 24/7, and accept it! But the Marxist brand of logic failed, because East Germans kept wanting to flee to the West; and they had plenty of motive, after all! They wanted to drive a Mercedes instead of the East German Trabant, a pitiful piece of a car with a lawn-mower engine.

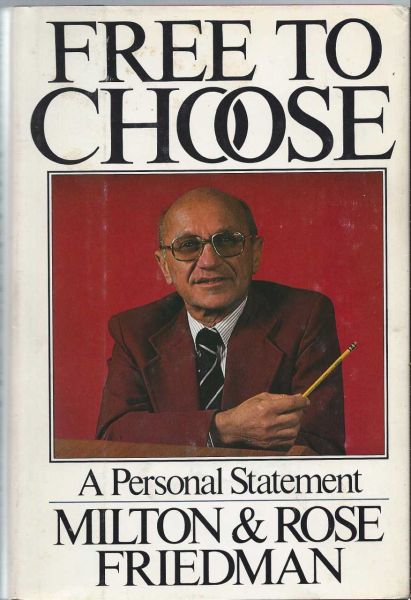

The late Milton Friedman and his wife Rose also believed in reason-as-motive and described their reasons in a book Free to Choose, published in 1980. People don't think along logical planes. They only pretend to, if you force them; so a government should concern itself with preserving a citizen's right to choose. If you give them a choice, their motives will decide for them.

The left-wing reason-as-logic, for example, dictates that we should all care for the poor; we should tolerate each others' differences and preferences. But if we allow people to choose, they will want a Mercedes, not a Trabant; they will want money in their checking accounts, a full refrigerator, and a wardrobe full of nice clothes. The women will want jewelry, the men, a 54-inch OLED TV; and so on.

People who have money don't want to send their kids to public schools. They don't want to have to accept a government health-insurance plan; and they will gladly pay extra for the nicer products, if someone will offer them. If a government offers them money instead of services, many will choose the money, and make their own choices. Freedom to choose really means the right to make choices as a consumer, rather than as people programmed to think a certain way.

The left-wing reason-as-logic thing does not work humanely, because it never ventures outside the box. The Friedmans' thesis, freedom to choose, really means the freedom to think outside the box. We allow ourselves to judge the World around us empirically and base our conclusions on our own sense of judgment. We reserve for ourselves the right to dissent and to reject the prevailing popular viewpoint.