Return to Erfurt

Starting on 26 August, I had my first visit to Germany in two years. I had kept my fingers crossed until I actually boarded the plane. It took off from the airport, and I was on my way. With America's Covid cases skyrocketing again, I had wondered whether I would get to go, at all. I also had doubts about the wisdom of such a trip, but it went off without a hitch. I did everything the airline and the German government wanted me to do, as regards the Covid epidemic—vaccinations, a molecular Covid test, and enough masks to last me a year.

I had to wear a mask everywhere, I had to deal with scaled-back services, and the stubborn worry about getting sick; but for me personally, the real discomfort of such a trip results from having to focus my brain on the task at hand, adopt a real-time mindset, and discipline my writer's powers of imagination—what the Germans call Fantasiekraft. Otherwise, you might find yourself on a train headed for Warsaw, Poland, with no recollection of how you got there.

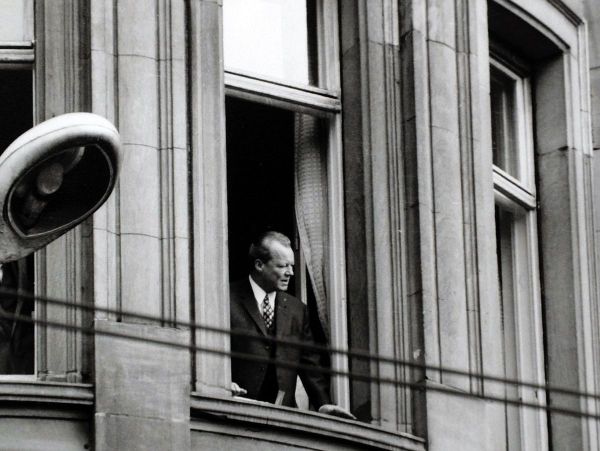

I stepped off the train in Erfurt, in the former East Germany, went through the railway station, and onto the Willy Brandt Platz. The Willy Brandt Platz commemorates former West German Chancellor Willy Brandt who visited Erfurt in 1970 in an effort to normalize relations with the East German government. His presence in Erfurt drew crowds of well-wishers—many of them no doubt wishing he would take them back to West Germany with him. Photographs of him looking from the window of the Erfurter Hof Hotel are ikonic in Erfurt history.

Erfurters renamed the Erfurter Hof the Willy Brandt ans Fenster, or "Willy Brandt at the window," in his honor. At night, lightbulbs embedded in the letters of Willy Brandt ans Fenster turn on and shine brightly across the Willy Brandt Platz.

The Soviet Occupation of Erfurt ended nearly twenty years later, and the task of taking up the reins of power and governing themselves proved a greater task than anyone had imagined. As hateful as it sounds, people used to submission to a dictatorial authority find the challenge of freedom as great as the challenge of slavery. Suddenly, the people of Erfurt had to create their own local government and the departments necessary in any effective administation.

Just creating the local government, just electing people to serve in positions of authority and finding suitable personnel to pursue improvements to the city's infrastructure takes time, and by the time the government had collected all the reins of authority, a few years had passed, and conditions in Erfurt had slid downhill. The stately Erfurter Hof fell into disuse, as well. Note the rusty duct-work in the lower left of the photo and the boarded-up windows.

For one thing, who owned the physical property of the city, now? As a Soviet nation, property had belonged to the people—practically speaking, to the government. In 1949, the Soviet government had confiscated all private property, with no compensation, exactly as Marx had suggested. After forty years had passed, few people in East Germany could sense the utility of private property any longer. Soviet spin-meisters had muted the innate potential of private property and other freedom-loving concepts—relegated them to an Orwellian memory-hole. No one dared talk of bringing them back.

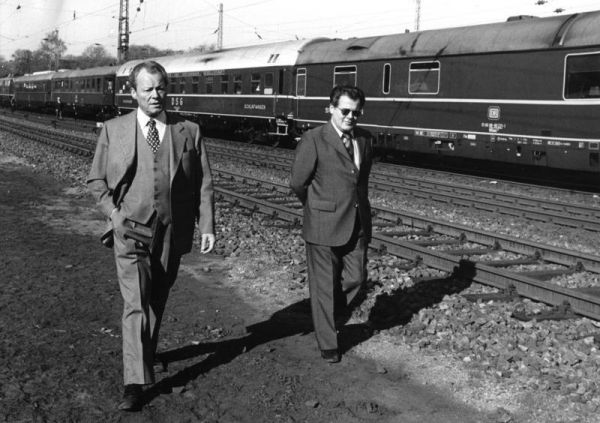

Willy Brandt himself did not escape the problems that the Soviet administration of East Germany posed for the freedom-loving West. The West German security agency unmasked Brandt's closest advisor Günter Guillaume as an East-German double-agent. Sadly, Guillaume felt no qualms about ending the career of the noble Willy Brandt—an anti-Nazi resistance-fighter based in Norway—long before it should have ended.

Guillaume had entered West Germany as a "refugee of totalitarian East Germany," which sounds just cynical as hell. Ironically, his unmasking damaged relations irrevocably between the East and West, creating far more problems for East Germany than any amount of successful spying could offset. Thanks to Guillaume, West Germans never trusted the Soviets again.

Lunch With Willy Brandt

The Willy B. restaurant and bar lies directly across the Willy Brandt Platz from the railway station. Once you enter the restaurant, you cannot miss the adulation that the owners feel for Willy Brandt. Curiously, "Willy Brandt" was only a pseudonym for a man named Herbert Frahm, who adopted the Brandt name to protect his family members still in Nazi Germany.

I went in Willy B's and ordered something to eat. The place is almost empty because Germans like to sit outside. As I waited for my order, I listened to the satellite radio play different selections from the House-music scene. A duo calling itself Semedo and Curtis Gabriel played their hit song "Some People Say." Most House-music bores me, but as I listened, I heard a familiar voice say "We are at the same crossroads again. It may be too little, too late."

The same authoritarian voice shouted at his audience, "You're so envious of one another! So petty!! You don't want nobody to outshine you!" I recognized the voice of Louis Farrakhan from the start. He gathered his strength and bore down, "If you don't get your act together, there will be blood in the streets!!!"

I had heard the voice of Louis Farrakhan many times before, and I wondered which audience was getting the business from him now? Disobedient schoolboys or drunkards at a rescue mission? So I looked up the speech by Googling the words "if you don't get your act together."

Turns out the speech took place in 1999 at the Cook Convention Center in Memphis. The audience consisted of 7000 Black Muslim dignitaries, the men in black-tie, the women in white burkas, but the speech was clearly intended for Black Americans across the country. Farrakhan skipped the usual denunciations of Jews and whites and instead went after the leadership of Black America.

He was especially critical of black leaders' efforts to fight violent crime in black neighborhoods. "Let me say something to you. You elders that have abandoned responsibility to our children . . . I want you to hear me! Black communities all over the country have become toxic places, and must be cleansed and restored from within."

I was surprised and elated to hear biting criticism from such an important figure. But try looking for references to the speech on-line. Most of the websites never mention it. Black people do not want to hear criticism. Their leaders know it, so they never mentioned Farrakhan's speech. Black Americans hate criticism, but there isn't much criticism of Black America, so it must resonate hurtfully in their own hearts. They know they are selling themselves short. How terrible to hate having to listen to criticism, but not to have the courage or the support of their leaders to act on it. Their own leaders block the path to redemption.

Farrakhan could have said more than he did, namely that most black leaders get their prestige, street-cred, and paychecks from the white elites. They can crow all day about white racism, but they clearly like white prestige more than the praise of their own people. Farrakhan's references to pettiness and envy are clearly aimed at them.