Sex and Political Power

Secular Monarchs

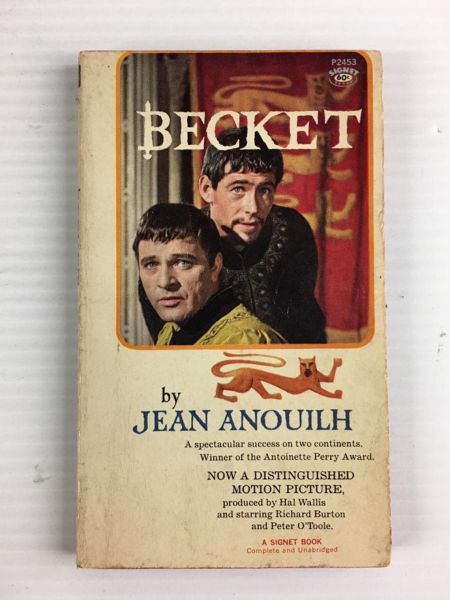

Richard Burton, as Becket, on the left; Peter O'Toole, as King Henry II, on the right

The French playwright Jean Anouilh published his four-act play Becket In 1960. Just four short years later, Becket became an epic feature-film. The director and producers of the movie hardly waited for the ink to dry, before filming it! Wikipedia portrays Anouilh's play and the 1964 movie as a "deliberately ficticious" work—which I suppose is a partisan attempt to water down the serious issues of the play and to salvage the reputation of monarchs—including presidents and their spouses. Becket plays up on the drama between two protagonists, the English King Henry II and Thomas of Becket, Chancellor and later Archbishop of Canterbury. The lively dialogue and the conflict between the main characters assures the play a measure of credibility.

Peter O'Toole played the role of King Henry II for the 1964 movie—brimming over with cheeful menace and glee. His imperious Henry is a short-tempered personality and impulsive womanizer. Richard Burton is also good as Becket, the title character—cheerless, ingratiating, and subordinate.

In Act One, the King and Becket get caught in a thunderstorm. To get out of the rain, they pay an unscheduled visit to a peasant family they pass on the way. Becket tells a boy to take care of the horses and to let them remain in his barn until the storm ends, when he and the King can leave again.

Henry's subjects know they had better not deny their King entry, and they had better wait on him. The King's imperiousness lets the reader know he goes where he likes. The sanctity of the home, safe from unlawful search and seizure, does not exist here. King Henry demands that he homeowner bring him something to drink.

Henry takes note of the homeowner's daughter and sizes her up:

King: What do you say to that, if it's cleaned up a bit?

Becket: (Coldly) She's pretty.

King: She stinks, but we could wash her. . . . How old would you say it was, fifteen,

sixteen?

Becket: (Quietly) It can talk, my Lord. . . .

The King has settled himself on a bench . . . whistling to himself. He lifts the girl's

skirts with his cane and examines her at leisure.

The peasants in this scene are in a real fix, inasmuch as the French King has little regard for his Saxon subjects; but if something bad happened to the King, they would worry about the future, until someone installed another king to take his place. Do they complain inwardly over his treatment of them? Practically speaking, it is immaterial. They need leadership that demonstrates its strength from time to time.

Norman King Henry II by an unknown painter

Having grown up in a nation that values its civil rights, my reader will probably react with hostility and loathing to the King's arrogance. For his subjects, however, actually living during his reign means accepting the King as the embodiment of the kingdom. Thus, he defines his nation, and his subjects regard him as a spiritual father, as little less than an emissary of God Almighty. If he makes a public appearance, his subjects would make every effort to go see him. They would hate to miss an opportunity. They hardly have a life apart from him. That kind of society runs on a different ethos from modern societies.

Church Monarchs

According to the play, King Henry II had a total lapse in judgment about his relations with Becket. Henry wanted to gain more power against the Church, so he proposed to make his friend Becket the new Archbishop of Canterbury. The Church's agricultural sector and its religious-trinket business turned a tidy profit. It paid its employees next to nothing, so he believed the Church should pay a tax on its profits. Church leaders absolutely refused.

The King also believed that "criminous clerks," that is to say men and women "of the cloth," and even church officials, were getting away with murder against private citizens. The two societies, one religious, the other secular, co-existed uneasily during this time, albeit on an equal footing. If "criminous clerks" committed crimes against private citizens, they stood trial in religious courts, which treated them more leniently, instead of secular courts, like everyone else in the Kingdom.

Although the Wikipedia articles on Henry and Becket do not mention it, I assume the crimes included sexual ones against private citizens and against school-children. My reader should easily discern the ramifications of these issues in our modern society. In the 1980s and '90s, when the modern Catholic Church pursued lenient measures against its "criminous clerks." It enabled them to prey again and again on young boys and did little to stop them.

The Church's lenient punishments of its employees did not suit Henry II, either, so he enacted the Clarendon Constitutions in 1164 a.D. in order to pursue justice against the criminous clerks in secular court.

I can see the justification for Henry's action, but what about a harder line against that other "criminous clerk," the King himself? Henry related to Becket how he tried to seduce a girl. His actions put her in a real quandary—resist the leader of the nation, or let him violate her oath of chastity to the Lord. Accordingly, she chose to take her own life.

Henry talks to Becket about it at the end of Act One:

Henry: I had no pleasure with her, Thomas. She let me lay her down in the litter,

limp as a corpse, and then suddenly she pulled out a little knife. . . . There was

blood everywhere . . . I feel quite sick. . . . She could easily have killed me

instead.

He appears to lack any remorse or sense of responsibility for what happened—just a childish "Thank God, she didn't kill me!"

Becket as Archbishop

What the King wants, the King shall get, by hook or crook! If he wants Becket to be Archbishop of Canterbury, then he shall have his way! Church officials argued that the requirements for the bishopric excluded Becket. Becket himself warned the King that the investiture would require him to answer to a different authority, and that he would come into conflict with the King. Henry disregarded the warnings and brought the subsequent misfortune on his own head.

The investiture led to one controversy after another. All of a sudden, Becket stands equal footing with Henry. His investiture makeshim a monarch, too. He takes his place in the never-ending battle between church and state authority—firmly on the side of the Church. Becket supports the Church's pursuit of legal authority in prosecuting "criminous clerks," against King Henry's intentions.

One wonders if Becket secretly loathed Henry's excesses and contempt for any kind of limit on his power. Maybe Becket hated having to subordinate himself to the King, who behaved like a spoiled, temperamental child. Now he had some authority of his own, and he used it with determination and spite against his former lord.

King Henry let his knights murder the Archbishop inside the Cathedral, a stunning act of violence. Afterward, prostrate with grief, he knuckled under to Church authority. As pennance, he entered the Cathedral, disrobed, and allowed the monks to beat him with whips.

The quest for supremecy remained in stasis until King Henry VIII, who directed his own knights to ransack Canterbury Cathedral. They smashed countless stained-glass windows—"Rattle down Becket's glassy bones!" said one iconoclast—and destroyed his costly shrine, decked with gold and precious stones.

The war continues. . . .

Stained-glass image of Thomas of Becket, Canterbury Cathedral

Experiences like this persuaded the Founding Fathers of our country that we needed a society where no one stood above the law, neither officials of the church, nor the state. Both systems, the monarchical and ecclesiastical, have imperious presumptions that neglect the civil rights of ordinary citizens, their individual initiative, and creation of wealth, which the Founders saw as hallmarks of a free society.

The Founders wanted a nation defined by laws, not arbitrary human leaders, so they fashioned our Constitution along those lines. Its archaic language from the eighteenth century on aged paper may not impress everyone, but our leaders have maintained its authority for two hundred years, and our nation has prospered as a result. Experience has taught us to trust it over the sweet-talking of our own leaders. We count on it to establish the limits and to keep in check the never-ending quest for power by political and social institutions.