Socialism and the End of East Germany

East German Implosion

My immigrant ancestor from Germany, John Siegling, came to Charleston, South Carolina, in about 1818. Not more than a year after his arrival, he opened a music shop for instruments and supplies. How he—a foreigner—could do that so quickly amazes me. Where did he get his start-up capital? Why not start his career under the tutelage of an established shop-owner first, or find a partner to shoulder the responsibilities? He obviously had an outlier grade of self-confidence to start his own business and make it succeed as well as it did. Americans cannot discount the entrepreneurial energy that immigrants bring to America.

Old Siegling Music House at 243 King Street, Charleston, South Carolina

Like a lot of immigrants, he sent money home to his family in the Old Country. He had a big family of brothers and sisters back home in Germany who were struggling to make a living, and parents who had their own needs as they grew older. Not surprisingly, some of his siblings wanted to come to America and take advantage of the opportunities here.

I learned a lot about their aspirations when my mother found a box of old family correspondence in about 1993, mostly letters from the German side of the family addressed to John. I speak German, so Mother asked me to translate them, which I did, and they sort of changed my life. For one thing, I became interested in Great-great-grandfather's hometown in Germany, Erfurt, in the former East Germany.

The Berlin Wall came down spectacularly in November, 1989. In the East Berlin Schauspielhaus, Christmas Night, 1989, Leonard Bernstein conducted an orchestra and a choir of 200 to perform Beethoven's 9th Symphony. My readers can hear it on YouTube. It enthralled the Berliners the way it has enthralled generations—its affirmation of human life and the drive toward personal happiness. This affirmation appearing especially after the the Fall of the Berlin Wall made it a seminal event—proof that individual initiative supported by capital in the context of a freedom-loving nation works, and the regimented egalitarianism offered by Marxism does not.

The concert-organizers changed the words to the choral movement, from "Ode to Joy" to "Ode to Freedom;" but I maintain that Schiller was right and the organizers wrong. People want joy more than freedom. The collapse of the Berlin Wall had as more to do with poor living conditions and the lack of consumer goods, than it did with a love of freedom. That's only human nature. East Berliners could pick up West Germany radio and knew that West Germans enjoyed a huge retail trade and could buy almost anything they wanted.

Rehabilitating East Germany cost West Germany a fortune, perhaps three trillion dollars, to replace water-works, clean up toxic waste-dumps, replace obselescent telephone systems. The list goes on and on. Marxist socialism condemned East Germans to something less than a Third-World peoples-republic. Industrial installations were so outdated, they had value only as scrap-metal. Most homes in Erfurt used coal-stoves for heat, but the smoke from the high-sulphur coal poisoned the air so badly during the long winter nights, it was unsafe to go outside. The caustic smoke even melted the stucco from exterior walls.

No one on the Left, neither in East Germany, nor in this country, wants to admit that modern nations cannot succeed without capital. A nation like East Germany had nothing to offer the community of nations but left-wing moralistic slogans and a dispiriting, regimented lifestyle. East Germany could serve as the poster-child of all the nations that declare war on capital. They might as well practice blood-letting again as a medical procedure. Everyone else wants capital transfusions.

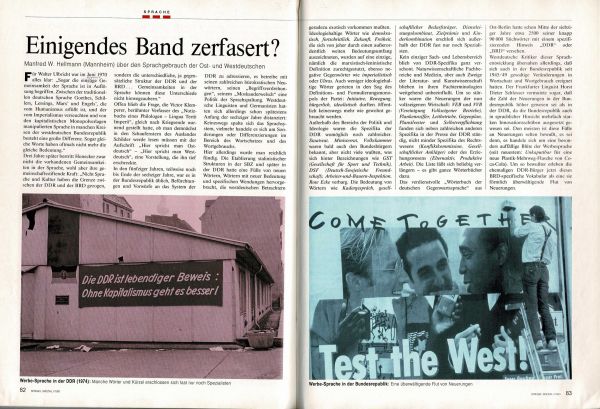

We can see in this issue of Der Spiegel a comparison of advertisements in East and West Germany. The banner tacked to the side of the building in East Berlin reads, "East Germany is living proof! Life is better without Capitalism!" It is just one of many tedious slogans. In the West German cigarette advertisement, joyous, sociable people light up. "Test the West!" would appeal to many East Germans starving for a better life than they have.

With no capital, East Germany could not renovate anything, could not upgrade exisiting facilities, or fund private start-ups. The abolition of private property meant that the government had to run the factories and create the shops. It provided the only economic vehicle the East Germans had to give themselves a decent life. Like government services anywhere, bureaucratic routine prevailed over creative measures to develop products or a customer base. The bureaucrats saw no need to improve anything. They only answered to their superiors.

East Germans made a joke out of bureaucratic snafus. If they saw a line of people at a retail-outlet, they reflexively got in line, too. The Soviet Eastern-bloc nations never had enough retail-outlets for their government industries, and the outlets routinely ran out of consumer goods. East Germans had a catch-as-catch-can attitude about the availability of consumer goods. In the photo below, people stand outside in the snow waiting for the bakery to open, hoping they can stock up on bread products.

Place a hundred citizens randomly in a nation that permits private capital to fund business start-ups, and they will stay put. Then place those same citizens in a nation governed with socialist central-planning, and they will want to leave on the first day. No one needs to test people to prove the truth about the two systems. Everyone already knows socialism doesn't work. If you said, "Let's go create a socialist nation and put these concepts to work," everyone would snicker at your naivté. They are not cynical, just realistic. How then does Bernie Sanders attract so many young voters? He does it by acting like an evangelist. His followers want faith in something, not a legislative agenda. No one wants to actually live in a socialist nation, just condemn others to it.

My First Trip to Erfurt

I did not actually visit Erfurt until nearly nine years after the Fall, during the cool, rainy summer of 1998. I spent most of two weeks taking in a wonderful old city that had lived under the yoke of a dictatorial socialist regime for the last fifty years, and it was terrible. I wanted to leave again. In the celebrated Altstadt, dingy, abandoned buildings had empty, darkened windows. The people shuffled past me looking hollow-eyed and depleted. Construction-sites with cranes and scaffolding marred the view, complete with stacks of building materials.

The people would remind some Americans of the Soviet Union: sinister youths with pit-bulls, jolly boys and girls begging for spare change. Fortunately, I met some interesting, knowledgeable people who knew about Erfurt's historical ups-and-downs and remained positive about the future. I toured Erfurt with them and looked at the medieval and Renaissance-era buildings badly needing repairs. The referred to them as "unpolierte Diamantsteine," unpolished diamonds.

But a lot of Erfurters decided that life in West Germany was too good to pass up, and they did not want to wait for an influx of capital from the West to improve conditions. They packed up their tiny East German cars and relocated to the West, or else travelled by train and abandoned their cars. The East German Trabant make a distinct sound, like a noisy mo-ped covered with a car body and four wheels. YouTube videos show American car enthusiasts driving them.

East German Trabant

Once I toured Erfurt, I understand why so many East Germans moved to the West. The contrast was as great as Antarctica and the rain forest. There were almost no shops in Erfurt in those early years, as the East German economy went over to the Western capitalist model. East Germans had listened covertly to West German radio every night and knew they could buy anything at department stores in the West, and they wanted some of that, too.

Even after nearly nine years of continuous work, Erfrurt still looked grim and gloomy, so much so that I wanted to turn around and leave. So much remained to be done. Buildings needed to upgrade their wiring, plumbing, and heating. Most older buildings have no air-conditioning, as Americans think of it. Germans just open their windows and turn on a fan.

Erfurt Andreasviertel, 1990

These images remind me of the TV program "Life After People," broadcast on the History Channel starting in 2008. Erfurters had to sit and watch their neglected buildings collapsing around them. They complained that, during the Soviet-era, the government routinely neglected their buildings—not making repairs for years. But they couldn't repair buildings if they lacked the capital to make the repairs. Considering the East German antipathy for capitalism, the lack of repair-capital should not surprise anyone. They might as well hate money. It is unrealistic to expect ordinary people to behave like that. Most people would love to have more money—their own, or even someone else's.