Stuck Ness Monster-part two

When Girls Get Stuck

Whereas the majority of book-readers read a book once, then move on to something else, a writer will work on a book like a cow chewing the cud. He will mull endlessly over its internal movements, study alterations in its spiritual ambiance, ponder its dialogue-flow, and sort out its social logic--what works or doesn't work.

Dialogue makes a book for me. The flow of dialogue can condemn a good thematic plan to mediocrity, or elevate a humdrum story to classical status. A good book does not require a clever or intricate plot. If its social functionality convinces a reader, a book can gain a foothold in the market.

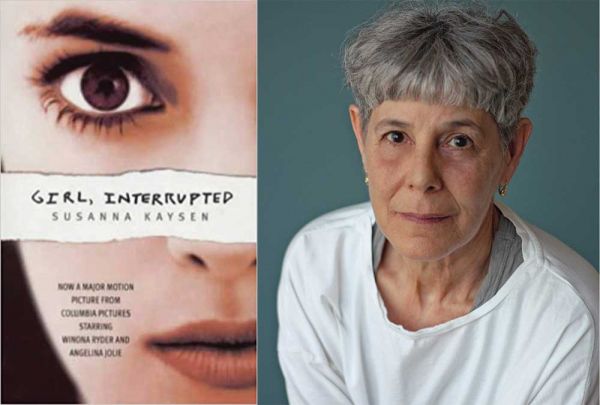

So when I read Girl Interrupted the first time, about a group of girls in a psychiatric-hospital ward, I found myself trying to figure out how the book had achieved its wild popularity, in vain. I just couldn't figure out Kaysen's magic. Her book did not impress me. In fact, its non-sequential story-line, its careless or superficial handling of doctor-patient relationships, and author Susanna Kaysen's omitting her familial and personal background left me trying to grasp an illusive personhood, see any gleaned insight from her retrospective view, and basically her reason for writing Girl Interrupted.

So the book's success surprises me. Kaysen shows almost no ability or inclination to understand the constellation of her thoughts, feelings, or fleeting impressions. The other patients experience one crisis after another, while the narrator remains a precarious observer, waiting around for something to happen, wondering why her doctor put her in the hospital in the first place--like a girl with a medical condition, rather than a psychological one. She suggests that neither the therapy sessions three times a day, nor the drug regimen helped her at all, leaving her a hardened woman and bitter ex-patient.

As I returned to the book again and again, I kept wondering why Kaysen couldn't select a few definitive interactions with her parents, or even make up one or two. Just a few snippets of actual dialogue with her therapists would help.

Instead of doing any of that, Kaysen includes actual pages from her doctors' diagnostic notes, nurses' periodic reports, and the official comments of her therapists to explain her hospitalization--as if she, alone, cannot explain it. The mental illness impairs her functioning to the point that she cannot focus on the causes, cannot remember her upbringing, or ponder her therapy sessions. All of this gives Girl Interrupted a kind of understated poignance. In the hospital's diagnostic notes, the reader learns that the doctors describe Kaysen as a "Borderline Personality."

I looked up Borderline Personality Disorder on-line and realized that I have had a relationship with a borderline-personality. Since the disorder afflicts mostly intelligent girls, lots of college boys know one or two of them. As the boyfriend, as the lover and sharer of all her personal experiences, I have come to a few conclusions about Borderline Personality Disorder, myself:

- The Borderline lacks personal continuity. From one day to the next, she may experience difficulty defining herself, maintaining her core beliefs, and a consistent point-of-view. She will have doubts about her personal connection to significant-others, where she even "forgets" them. But the borderline has to persist in connecting to others, lest she retreat dangerously into herself.

- The part of the brain that calls to life the individual ego does not fulfill its task--called "individuation" by some psychologists. The ego as a definer of personality, that gives recognition-value to a person in the social realm, never gains needed integrity and dimension. The patient remains like an infant experiencing Terrible Twos--stuck in transition. Significant-others are either too close or too distant, like a no-man's land with a non-existent comfort-zone. She mistrusts others' intentions toward her, but remains dependent on them and cannot bear any separation. Her lack of authenticity depresses her spirits and leaves her disoriented, especially in the intimate realm, where she must represent herself to her lover. The most she can do is perform for others.

- The Borderline lives almost entirely in real-time and has little patience or inclination for reflection or doubt, which, by trial-and-error, helps create the individual's personal philosophy and moral dimension. These things contribute greatly to an individual's personal stature and spine. If Americans expect to extricate themselves from the muddy stasis of disunity, they have to develop ego-strength to give them the spine to act.