The Disruptive Dynamic

THE DISRUPTIVE DYNAMIC

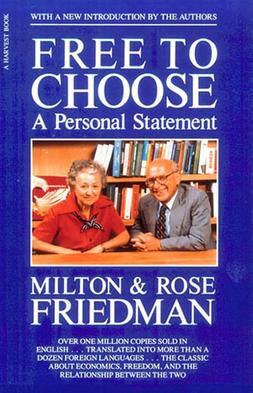

Professor Milon Friedman and his wife Rose worked as economists in their lifetimes and published Free to Choose, like a personal memoir, in 1980. As the book grew in popularity, Friedman filmed explanations for the themes of the book. My reader can view them on YouTube. Friedman features topics like "The Power of the Market" and "The Tyranny of Control."

Freedom to choose really means freedom to create; but an article that I saw in Die Welt newspaper in Germany, during my last visit in February, said that the freedom to create can take on disruptive proportions. Hence, the title of the article "Die Dynamik des Disruptiven." It really means that the freedom to create includes the freedom to create havoc.

Innovations in business practices and in industrial production flow at a regular rate, until someone gets it into his mind to overhaul everything and start afresh, with new methods, new technologies, and a whole line of new, must-have products, that render everything else, produced up to that point, as obsolete.

The "river of innovation," writes the author Ulf Poschardt, grows from a regularly flowing river into a "stürmisches Meer mit Monsterwellen," a raging torrent, sweeping everything before it. No matter how much Americans hail the new technologies and the new products that result from them, others see the new products as creating unmanagable challenges and lots of wastage.

A whole new generation of businesses and entrepreneurs make new fortunes, and everyone else has to scramble to catch up, or just salvage what they have, and make a graceful exit. I can remember how customers crowded into department stores, fighting for the last copies of Windows-10 from the dwindling inventory. News-cameras caught their screams of triumph as they departed; but the news that the store had run out of Windows-10 triggered near-riots.

I experienced this myself in 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic set in. In a computer shop, I managed to snag the shop's very last Zoom camera, which saved me during the Lockdown, because I could socialize on-line with people face-to-face. Each time I contacted people over Zoom, I could hardly believe my eyes! The human confrontation engaged me more than telephone calls did. They could see me; I could see them.

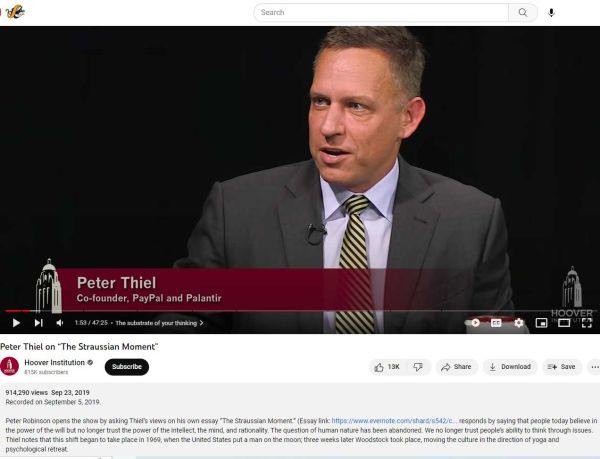

Poschardt writes that the German entrepreneur Peter Thiel criticized President Trump, whom Thiel supported, for not pursuing a policy of "Diskontinuität"—departing from the past—more decisively. Thiel has the goal of pursuing discontinuity profitably in every aspect of the nation's economic life. For him, "Bequemlichkeit und Konformismus" (complacency and conformity) define life in Silicon Valley more than innovation and personal initiative. Thiel even uses the word "Gleichschaltung" to describe the level of conformity. Dating from the Nazi-era, "Gleichschaltung" means that everyone must connect to the same control-panel for instruction and orientation.

Poschardt contrasts this with 19th century Germany. The presence of people like Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche, Karl Marx, and others made Germany a "philosophische Supermacht," or philosophical superpower. It did more than that. It helped people understand the importance of philosophy as the force to potentially remake the German nation. Those philosophies have contrasting attributes that make them compete with one another to give the nation its identity, inasmuch as they represent different value systems.

Poschardt goes on to talk about how philosophy can fuel "disruptive Innovationskraft, Entwicklung, und ein selbstbewusstes . . . Unternehmertum" (disruptive innovative energy to develop a confident culture of entrepreneurship).

But just as philosophy gives a citizenry its cultural identification, orientation, and political allegiance, it also divides citizens. The divisions make many people paranoid and insecure—thus, the endless rhetoric about tolerance and diversity, to smooth over and obscure the divisions. Poschardt says the disunity presents problems for Germans, inasmuch as it makes them risk-averse. Instead of moving forward, they fidget nervously, trying not to attract notice.

Rather than risk more division, Germans—like Americans—would rather dampen the enthusiasm for free speech, quell the desire to take dissenting positions, challenge prominent presumptions, or advocate about-faces on important issues, that might provoke an unpleasant response. One blogger, posting on his Facebook-page, offers the zipper as a metaphorical "unifier" of people—as good as saying "Draw that zipper closed; bring people together, whether they like it or not." It is hilarious and scary, at the same time. "Zip your mouth, while you're at it!"

Thiel, on the other hand, makes dissent part of the creative disruptive process; and just as business enterprises innovate, reconfigure, and sometimes disrupt their processes, so must nations. The only way to save them is to innovate. If the nation refuses to do this, then violently disrupt the creeping intertia of fear and timidity with "a little revolution," as Thomas Jefferson once said. A revolution, in our case, should do exactly what the American Revolution did: divide our disunified nation into new energized nations—moving forward, because they must.