The Enigmatic Noel Field

The Story of Noel Field

Years ago, when I lived in Greenville, South Carolina, I patronized the main library at the corner of North Academy and College Street. The same building now houses the Children's Museum of the Upstate. As I walked up the paved path over the front lawn to the entrance, an old man approached me and offered to tell me about the Bahá'i Faith. I said no politely and continued on. When I looked behind me, I saw that he had already greeted the next person, fifteen feet behind me, with the same spiel. I encountered him perhaps a half-dozen times at this location.

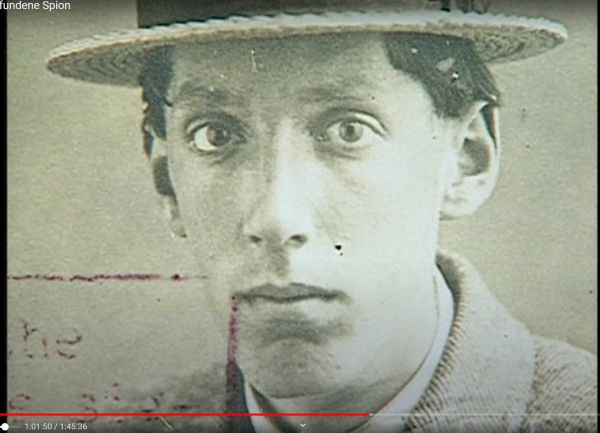

At that time, I had never met anyone like him. He was tall, pale with mottled skin, and skinny, with a straw-hat to shield his face. His large blue eyes radiated a gentle conviction about the rightness of the Bahá'i Faith, as the key to a fulfilling life. He never remembered me from previous encounters, nor asked me about myself. He went for volume conversions, but the absence of honest humanity in the man turned me off.

After I moved to Charleston in 2002, I did not think of the Bahá'i-man again until a trip to Germany in 2018, when I saw a documentary on the TV titled Noel Field: der erfundene Spion (in English, "Noel Field: the Invented Spy"), directed by Werner Schweizer and released in 2018 to commemorate the victims of Soviet Purges in Eastern Europe in 1948, in which Noel Field played such a prominent role.

You could have superimposed Field's face on the head of the Bahá'i-man. Field's long face, large blue eyes and straw hat indicated a devout religionist. Noel Field grew up in Zürich, Switzerland with a British mother and an American-Quaker father. His father died before Noel's seventeenth birthday, and his mother moved Noel and his siblings to America. Noel graduated from Harvard University and started work in the American State Department.

No one knows exactly when Noel became a Communist, but he himself claimed an early attraction to Lenin and Marxism. He had to hide this from his colleagues in the State Department, but he tired of his deception after ten years. The State Department environment stifled his real intentions, to save the World; so he resigned from it to work for the League of Nations between the World Wars.

With Soviet talent-spotters trying to recruit Field to commit espionage, he quit the League and went into relief-work in Spain and southern France trying to alleviate the suffering of refugees fleeing the Spanish Civil War, many of whom were themselves Communists. Field's relief-agency took care of thousands of refugees. Soviet officials continued to try to recruit him. An American intelligence officer, Allen Dulles, also recruited Field to work for him, with the result that the Soviets trusted Field less and less. Dulles had quite a reputation already and later became the first Director of the CIA.

The Soviets also recruited Noel Field's Harvard-friend Alger Hiss. In 1949, Hiss went on trial for committing espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union. Fearing a subpoena to testify about his relationship with Hiss, and possibly implicating himself, Field fled the country. He landed in Czechoslovakia—the predecessor nation of the Czech Republic and Slovakia—to find work as a teacher.

Alas! The Soviets had led Field into a trap. Suspicious that Field actually worked for Allen Dulles, they took him into custody and beat a confession out of him that implicated hundreds of officials in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland—all of them loyal Communists, who had the misfortune to meet Noel Field during the War, and so likewise came under suspicion as agents working for Allen Dulles. Some theorize that Dulles played along with the Soviets' suspicions, in order to destabilize Soviet influence in Eastern Europe.

The Soviets held Field in solitary confinement and beat him half to death, seemingly in a fury over his alleged disloyalty. They held him for four years, along with his wife, his brother, and his foster-daughter. They broke his body, his will and spirit ,and left him psychologically scarred for the rest of his life.

How could Field have remained ignorant of the intentions and methods of the Soviet Union when it dealt with perceived traitors? Usually the Soviets shot first and asked questions later. Other people explained that Field was just congenitally naive. After his release, he met his wife for the first time in four years and asked her, "Did you remain loyal" to the Soviet Union? She said yes, and that was that!

We were not likely to find a man like Noel Field among our friends. While we played tennis, took girls on dates, or went swimming, Noel Field stayed ensconced in libraries, preparing for his career as a diplomat. Americans need to understand the motivations and character of men like Noel Field. He hid his intentions behind a liberal consciousness and humanitarian intentionality. He would likely never have admitted to anything voluntarily. We should thank the Soviets for beating the truth out of him.

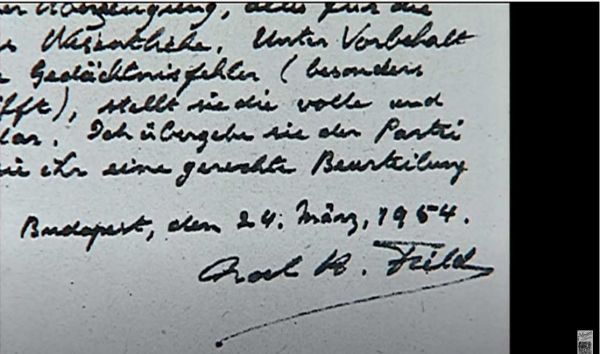

In a sixty-page handwritten confession prepared for his captors, Field bared his soul in a way that few men in his position—Harvard graduate, State Department officer, League of Nations officia—ever have to do. He described himself as timid and reserved, that he made few friends, and preferred schoolwork to living socially. In the dictatorial, secretive culture of the Soviet Union, he wrote his confession, believing that it would never see the light of day. He believed that he would never have to worry that anyone State-side would ever see it. Alas! he was wrong! My reader can find the entire confession on-line, albeit in German.

It is ironic that an achievement-based, freedom-loving society like ours could allow an intelligent, studious man—who accepted the dictatorial culture of his nation's enemies—to get as far as Field did. Odd to think that he could achieve so much and go awry socially and philosophically. I say this because Field never really explained why he remained loyal to the Soviet Union, after all it did to him.

Although I had never met anyone like the Bahá'i-man, I actually knew people like Field, who glibly accepted a Marxist posture, lived ensconced in classrooms and libraries, achieved academic success, and furthered their careers. Odd to think that high-achievement does not mean awareness of the fruits of liberty—and that high-achievers might actually work against the grain of the society in order to further the intentions of a dictatorship.