The Erfurt Synagogue Treasure

The Domplatz in Erfurt looking west, featuring the Cathedral and St, Severi Church. The 13th- century Bonifatiuskapelle in the lower right.

In the next photo, the Domplatz looking east

I am in Erfurt, Germany, again, my home-away-from-home. My Great-great-grandfather grew up here before going abroad about 1810, and finally settling in Charleston, South Carolina in about 1818. My mother found a bunch of his old family letters in an office-secretary, written by his father and his siblings still in Germany between 1812 and 1857.

Among other things, I am impressed by Erfurt's long and complex history. During my very first visit in 1998, for instance, I read that a construction crew was clearing a site to prepare it for new buildings, and discovered a hoard of ancient artifacts hiding in the rubble.

Curiously, the demolished buildings had only been there since World War II, but had already fallen into disrepair, thanks to East Germany's poor maintenance of its buildings. As the tractors moved back and forth, they ran over the artifacts and damaged a few of them. The construction crew turned over the artifacts to the city's archeologists, who pored over what they had found. The most interesting object in the Erfurt treasure was a gold wedding-ring engraved with Hebraic letters. The wedding-ring and Jewish motifs on other objects confirmed that the treasure had belonged to a member of Erfurt's thriving Jewish community.

In addition to the jewelry, the treasure contained 3100 silver coins from the early-14th century, known in the trade as gros-tournois, that traded widely in Europe at that time.

It was a real treasure from the 13th and 14th centuries--wealth from a completely different culture: silver coins, gold jewelry, gilt-silver cups and pitchers. The most Americans can find, digging into the ground, is Indian artifacts or the remains of extinct animals.

In places like Erfurt, however, which has documented city-status since the 8th century, you can find the remains of extinct human cultures. You can see the remains of building-foundations below a differently configured network of streets.

The Jews had settled in Erfurt after its ruler, the Archbishop of Mainz published an encyclical that offered Erfurt-citizenship to anyone based on "libertas et iustitia," like the American "liberty and justice for all."

The Jews took advantage of the offer and settled in Erfurt. By the 12th century, they had built an impressive synagogue, which still stands, and settled the neighborhood around it; but they succeeded so well, the majority-gentile population turned against them.

The contents of the treasure reveal that the Jews wore bejewelled brooches and clips on their cloaks and robes, and enameled belts made of gilded-silver to wear around their waists. The city-authorities warned wealthy citizens against wearing so much jewelry, in order not to provoke poorer citizens. Mostly, wealthy people ignored these warnings.

1349 was a watershed year across Europe as the dreaded Black Plague took hold in city after city. Almost by design, Gentiles started looting Jewish businesses and homes. After the first signs of violence, wealthy Jews started burying their wealth, but driven from their homes, they could never return for it. The Erfurt city council confiscated what remained.

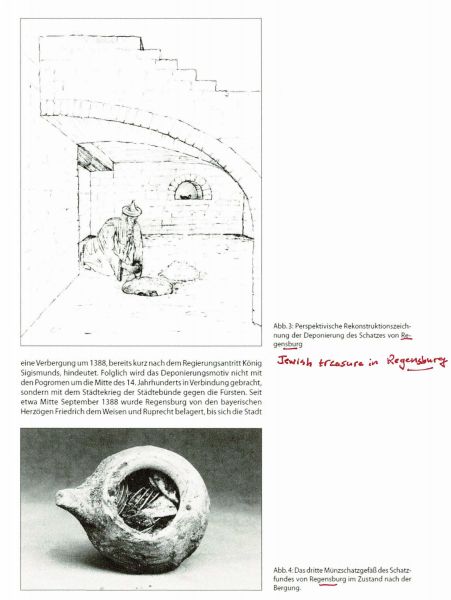

Such hoards have appeared in other cities, such as Regensburg, Germany, as well as other cities. Curiously, these other hoards also contained wedding rings and similarly-designed jewelry.

Everyone should have enough moral orientation to know the lessons by heart: Do not flaunt your wealth; do not covet other people's wealth. But history has moved mightily under the spell of envy and resentment. It has proven that wealth induces the most violent and vindictive form of envy. Why bother to steal other people's wealth, if you can elect political official who will get it for you legally, so to speak--giving you a justification for taking it?