The Gold Standard

The Gold Standard

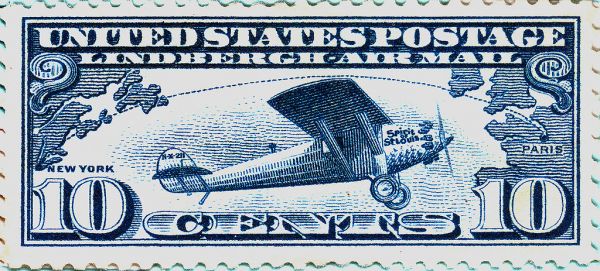

In 1927, an American aviator Charles Lindbergh made history when he flew across the Atlantic Ocean in the “Spirit of St. Louis.” He lifted off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island on May 20 and landed again 33.5 hours later at Le Bourget Aerodrome outside Paris. The flight covered an astounding 3600 miles, with an average speed of about 100 miles-an-hour..

Lindbergh encountered a number of problems during the long flight: icing, fog, and winds. The plane's enormous engine blocked his forward view. To navigate, he had to look out his side windows. He did not carry a radio or navigational equipment; just a compass, so he had to manage his flight-plan by “dead reckoning.” Wikipedia's article on Lindbergh said he had "reckoned" so well that he flew over the coast of Ireland barely five kilometres off-course.

As Lindbergh started his descent into the aerodrome in France, 150,000 people were en route greet him. While airborne, he had seen the headlights of their cars. They dragged him from his plane and carried him on their shoulders around the airfield for half an hour. He became an international celebrity overnight. The World's many nations sent him congratulations, in recognition of his achievement; but surely none more satisfying than the Congressional Gold Medal awarded him by the U.S. Congress.

None of the fanfare made him show much emotion. He received each honor studiously and unsmiling, as the hundreds of contemporary news-photos show. After the hoopla of his Transatlantic flight died down, he married Anne Morrow and retired to a rural estate in Hopewell, New Jersey, to raise a family.

His life changed forever on March 1, 1932, when his son Charles Lindbergh, Jr., was kidnapped from his home in New Jersey and held for a $50,000 ransom. The parents raised the money and delivered it, as requested, but they never heard from the kidnapper again, and all trace of him and their baby vanished.

Law enforcement officers and bank-employees had written down the serial numbers of the ransom bills, so that investigators could trace them back to the kidnapper. On this point, the administration of President Franklin Roosevelt gave them a fortuitous boost when it took the nation off the gold standard. It also required all American citizens to surrender their gold coins and “Gold Certificates,” the bank-notes that allowed conversion to gold coin. In their place, the government issued new “Federal Reserve Notes.”

I can remember my grandmother telling me that she did as the government asked and turned in her gold coins and certificates, but she also said that many of her friends kept their gold coins. They were suspicious of the Roosevelt administration's effort to get them off the gold standard. After all, Americans had used gold coinage since the late 18th century. Now, the government told them they could no longer use gold coins or even own them. They could only own gold-bullion with a license for gold jewelry or medals. The government fixed the price of gold at $35 an ounce.

At any rate, the conversion to Federal Reserve Notes made the kidnapper's ransom-money stand out. When the police started looking for him, they could just follow the money-trail—the gold certificates. He could hardly spend his ill-gotten gain without someone noticing. Each time he bought something with a gold certificate, the police closed in on him. Finally, a gas-station attendant waited on the kidnapper, who paid for his gas with a gold certificate. The attendant jotted down his license-plate number on the edge of a gold certificate, and the police tracked him through New York's Department of Motor Vehicles.

Even fairly innocent Americans could get into trouble if they did not obey the decision of the government regarding gold. They may have known that the government kept the price of gold artificially low and saw gold as a more reliable source of value than the dollar. Foreign governments, for instance, demanded payment in gold for the dollars that they held. Their savvy leaders knew they wanted gold instead of dollars, especially at $35.00 an ounce.

This went on for a deplorably long time. Market forces pushed the market price for gold higher than its official price. This incongruity led to a decline in America's gold reserve from 21,000 metric tons in 1957 to just over 8,000 tons in 1974, where it stands today. When the Congress finally relented, abolished the fixed-price approach, and allowed Americans again to own gold, its bidding price shot up. Today, private companies and individuals own thousands of tons of it. Released from price-controls, gold skyrocketed to its current $1821.00 an ounce.

In a sense, we all honor the gold standard, every time we lust for Lindbergh's Medal or a $10 Liberty-head gold piece. Gold has value in itself as a durable asset and can serve as a kind of economic indicator, because it reflects consumer confidence. When investors sense a downturn in the economy, they buy gold as a hedge, because of its historic ability to store value; but it can only serve as an indicator if it trades freely—free of interference by the government. The gold standard means more as a private institution, if you think about it.

Gold has a magisterial beauty that maintains an inherent value across the globe and all its people. Used frequently in religious art, it acts as a conduit to the divine. Men have lusted for it and killed for it at least since the time of the Pharaohs, according to archaeological evidence. No other substance on the planet excites us so.

The Limits of Gold

Currency in the US is printed and issued by the government. Nowadays, I really pay for things more often with a credit or debit card—a private intermediary, so to speak. Currency plays less and less of a role in our transactions. At least, people still call it “money,” and can hardly look at a satchel full of loot and keep a straight face about it. The handsome, high-tech banknotes are works of art.

Wealth, on the other hand, is a many-splendored thing, taking many forms. Perhaps 10% of the nation's wealth ever appears as cash. To understand the complexity of it, all you have to do is look at the accounting of a business. No one keeps a lot of cash around. Knowledgeable people sock it away in a myriad of forms other than cash—certificates, contracts, and other official-looking pieces of paper with gingerbread on them. Even ordinary business-letters can have legally-binding language that obligates someone to perform tasks, pay out monies, or else just to stay quiet, and don't make trouble. Even oral assent and handshakes can be legally-binding. Used skillfully, the handshakes and documents work like hydraulic fluid in a machine, greasing the gears of a vibrant economy and enabling forward-movement.

Often, documents transition into other kinds of documents—one kind of business activity evolves into another. Everyone counts on unfettered interchangeability and mobility, despite the inherent risks of identifying the evolving documents in a legal situation. It all adds up to trust or obligation that business-people count on, to provide financial support. In some instances, the documents and actions evolve into an asset known as “venture-capital.”

People pool their resources to launch a new product-line or business. It happens all the time, and God help us if the government puts the brakes on it! That goes for other forms of capitalism—research and development, plant expansion and re-tooling, or employee training. Everything costs money which, in one form or another, has to be available. Wealthy people sit around and wait for someone to come to them with a viable business concept. They meet, shake hands, and a pot of money awaits them if they succeed. We count on them to succeed.

Gold still plays a part, but it's just another asset. When merchants trade in gold, it takes the form of contracts. They never actually see or touch the gold, and increasingly, they never see a paper-contract. A computer stores all of the pertinent information in an electronic file. All that stuff takes place on-line, now.