The Green Party Should Turn Red

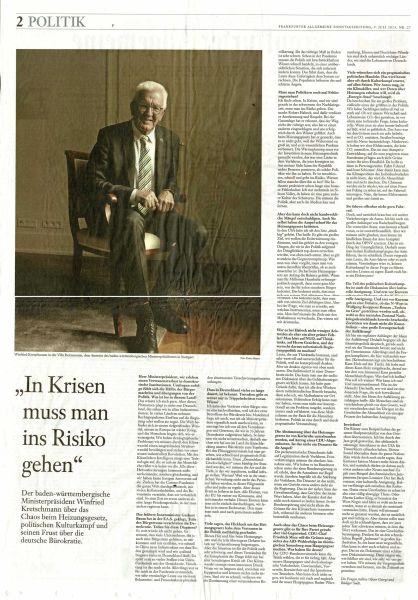

I saw this article about Winfried Kretschmann in the Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper during my visit to Germany in June and July. In English, it means "In ttimes of crisis, we have to take risks." Kretschmann serves as Minister-President of Baden-Württemberg—the equivalent of a governor in Germany—for the Green Party, Die Grünen. The Greens have represented themselves to the public for years as the party of the environment for its advocacy for the end of nuclear power, militarization, and the production of toxic garbage like plastic containers.

In the first question of the interview, the Frankfurter Allgemeine asks Kretschmann about the loss of confidence in Germany's democratic society. Kretschmann immediately directs blame for this on the Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD, a right-wing populist party in Germany—calling out the AfD for its radicalism.

Kretschmann does not mention any other radicalism in Germany—like Kevin Kühnert's, a leader of the Social Democrat Party in Germany. Kühnert describes himself as a democratic-socialist, which is a redundant term, since socialism is democratic. Kühnert says would like to nationalize German corporations like BMW and "collectivize" German society. Perhaps Kretschmann does not see this proposal as radical enough to mention in the interview.

So I decided to do a little more research into Winfried Kretschmann before I filed away the article. (I save newspaper articles—perhaps a thousand of them, so far.) Kretschmann started his political activities while still a student. Curiously, he started out as a member of the Kommunistischen Bund, with an emphasis on Maoism—while he lived in West Germany! I cannot find any evidence that he ever wanted to visit East Germany. How odd, at any rate, to call out right-wing radicalism without saying anything about his own.

Since Kretschmann had his own experience with radicalism, I thought I should research the other leaders of the Green Party for their histories. Americans will probably remember the now-retired Joschka Fischer—a burly, bespectacled rooster of a man—who served as vice-chancellor under the Chancellor Gerhard Schröder in the late 1990s. Fischer developed a reputation as a cocky, trash-talking opponent of Conservative politicians.

I learned that Fischer had quite a problem trying to justify his past—his involvement in the RAF—the Red Army Faction, whose murders of prominent Germans caused such concern in the 1970s. Fischer engaged actively in street-battles with police and used his own car to transport the pistols used in some of the murders! I remember my first visit to Germany in 1977, and the high-level of security in the Frankfurt/Main Airport on the day of my departure. I saw numerous police officers, always in pairs, toting HK sub-machine guns.

Germany acted like a nation under a siege-threat. While the German government had to deal with the backlash of law-abiding Germans reeling from the murders, Fischer refused to express remorse for their deaths. Imagine an American politician doing that, then trying to put his revolutionary past behind him. Fischer not only put the past behind him; he also excelled to new heights. I am sure many Germans never forgave him; but Germany has the same problem with disunity that America has, with one-half of the nation utterly opposed to the other.

Finally, I researched Jürgen Trittin, a Green-Party associate of Fischer's. More than anything, Trittin ruined his own reputation by signing off on a petition to decriminalize some forms of sexual conact between grown-ups and minors; but politically, he has taken the same path of left-wing extremism as Kretschmann and Fischer. Like Kretschmann, Trittin belonged to the Maoist-leaning Communist Bund. Like Fischer, Trittin expressed no remorse for the deaths of prominent Germans at the hands of the Red Army Faction.

As I have already written, it struck me as curious that the leaders of the German Green Party, well-known for its involvement in environmental issues, engaged first in revolutionary activities. They could just as easily have called themselves the "Red Party," except that red is already the color of the Social Democrats. The Greens would have to settle for an off-red, but not crimson, which the far-left party Die Linke already uses.