The History of Chef Boyardee

My family grew up with Chef Boyardee. We saw his face on the wrapper of every can of spaghetti, ravioli, and beefaroni that we ate. We never associated him with a real person who had a real life. He was just a cartoon-like character in a toque blanche, about as real as Bugs Bunny or Daffy Duck to a pre-teen.

In fact, Chef Boyardee was a real person—Ettore Boiardi—who grew up in Piacienza, Italy, then emigrated to the United States. Like so many successful people in our country, Boiardi grew up in obscurity, so no one knows exactly when he arrived here. The New York Times obituary said 1917, at age 20. The Wikipedia article said 1914, age 17.

The sources do agree he started working in a restaurant at age 11. After he arrived in the States, he started working at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. As Boiardi developed his craft, his customers began to notice him and asked him to make extra jars of spaghetti sauce for take-out. Then, he made spaghetti-kits for take-out, containing semolina pasta, spaghetti sauce, and pre-grated cheese. After a time, he opened his own restaurant under the name Il Giardino d'Italia.

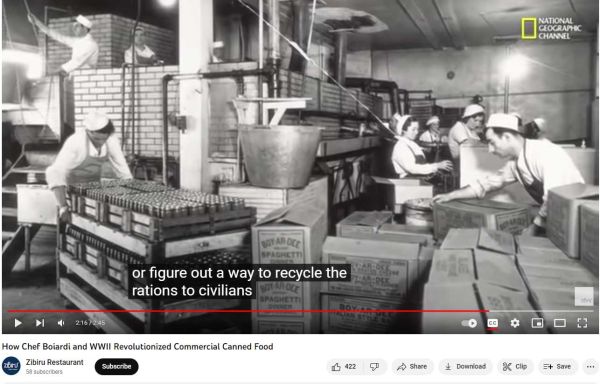

He carefully guarded the quality of his product, bought a factory to produce cans of spaghetti, and preserved space in the basement for growing mushrooms. Then World War II came along, and much like George Hormel—with the same immigrant energy—Boiardi joined the War effort and went into high-gear to produce ration-kits for the nation's armed-forces.

At its peak, the Chef Boyardee Company employed 5,000 people, ran 24/7, and turned out 200,000 cans of product every day. At War's end, Chef Boyardee had to scale down its production and lay off its work-force. Rather than do that, Boiardi sold the company for $6,000,000 to the American Home Foods Corporation—the equivalent of $90,000,000 in today's dollars.

After the War, with Boiardi's assistance, the company retooled to provide for a civilian market, and it succeeded beyong Boiardi's wildest dreams. He remained at heart a family man, his friends told reporters, who naturally wondered about the secrets of his success.

The secret of success in our country remains, as ever, the ability to offer services and products that others want—patrons of a restaurant, the military, or grocery-shoppers, in Boiardi's case.